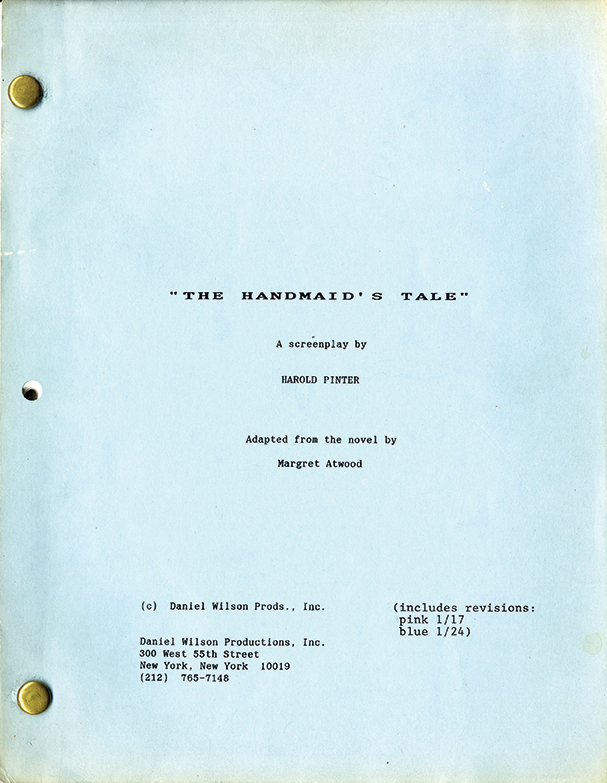

HANDMAID’S TALE, THE (Jan 1990) Screenplay by Harold Pinter, adapted from Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood (source), Harold Pinter (screenwriter) New York: Daniel Wilson Productions, 1990 [containing revisions dated 1/17 and 1/24]. Vintage original film script, quarto, brad bound, self-wrappers, 102 pp. Just about fine.

An important unpublished Harold Pinter screenplay, which is greatly at variance from the final film as released.

This film, directed by Volker Schlöndorff (THE LOST HONOR OF KATHARINA BLUM, THE TIN DRUM), taking over from original director Karel Reisz (ISADORA), is of principal interest today due to its exceptional cast — Natasha Richardson as Offred, Robert Duvall as the Commander, Faye Dunaway as his wife Serena, and Elizabeth McGovern as the lesbian Moira — and because its screenplay is credited to Nobel Prize-winning playwright and screenwriter, Harold Pinter. Pinter had previously collaborated with director Reisz on their 1981 adaptation of John Fowles’ THE FRENCH LIEUTENANT’S WOMAN.

However, according to Steven H. Gale, in his 2003 book Sharp Cut: Harold Pinter’s Screenplays and the Artistic Process:

“[T]he final cut of The Handmaid’s Tale is less a result of Pinter’s script than any of his other films. He contributed only part of the screenplay: reportedly he ‘abandoned writing the screenplay from exhaustion.’ …Although he tried to have his name removed from the credits because he was so displeased with the movie (in 1994 he told me that this was due to the great divergences from his script that occur in the movie) …his name remains as screenwriter.”

The completed film does not represent Pinter’s (or Reisz’s) original vision. When Schlöndorff took over the film’s direction and requested rewrites, Pinter suggested he enlist the original author (Atwood) and she, among several other people, were responsible for the final shooting script, which Pinter referred to as a “hotchpotch”. Thus, this original Harold Pinter screenplay draft — never published — is of tremendous value to scholars or fans of Pinter and his work.

Even the latest revisions on this draft, dated 1/24/89, are written in Pinter’s typically minimalist screenwriting style. Example:

EXT. TOWN CENTER – SHOPPING ARCADE — DAY

Offred and Ofglen walking. Various women with shopping baskets.

The arcade echoes with their footsteps. Most of the shops are shut.

Some “craft” shops and food stores are open.

From the beginning, Pinter’s plays (THE BIRTHDAY PARTY, THE CARETAKER, THE HOMECOMING) and screenplays (THE SERVANT) were about power struggles between individuals. As he grew older, his writing became increasingly political, increasingly concerned with the power of the state. Many of his later plays, e.g., ONE FOR THE ROAD (1984) and MOUNTAIN LANGUAGE (1988), are overtly anti-fascist. Pinter’s 1989 screenplay for THE HANDMAID’S TALE is clearly part of this same period in his work, equally concerned with the threat of totalitarianism to human rights.

Pinter’s screenplay begins in the “Handmaid’s Center”, specifically a gymnasium at night:

Faces of women, heads flat on beds, turned sideways, watching each other’s mouths in the dark, lipreading.

VOICES

(from bed to bed)

What’s your name?

Janine . . . Dolores . . . Alma . . .

June . . . Moira . . . Kate . . .

The movie, on the other hand, begins with an extremely high overhead shot of a car driving on a winding mountain road in the snow (reminiscent of a similar shot in Stanley Kubrick’s THE SHINING) on which the following title is superimposed:

ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE RECENT FUTURE A COUNTRY WENT WRONG. THE COUNTRY WAS CALLED THE REPUBLIC OF GILEAD.

Neither that scene or the superimposed title appear in Pinter’s screenplay.

While Pinter’s scene of the women whispering in the dark does appear in the movie, it comes much later in the narrative, approximately two thirds of the way through. Pinter’s approach to the story is achronological. Scenes of Offred (formerly Kate) and her husband prior to the fundamentalist Christian takeover of the country are intercut with scenes of Offred in the Handmaid’s training center which are intercut with scenes of Offred as a Handmaid (an enslaved surrogate mother) at the home of the Gilead Commander and his infertile wife. Schlöndorff’s film version preserves Pinter’s achronological approach, but transposes the order of scenes and shots, as though Pinter’s screenplay had been cut into scraps and the pieces rearranged.

Aside from rearranging the order of scenes, Schlöndorff and Atwood’s rewritten film version adds dialogue and actions to Pinter’s scenes, while omitting some of his dialogue and entire sequences. For example, the scene in which Ofglen (another Handmaid) first informs Offred that there is an underground Resistance to the Gilead tyranny — while both of them are looking at automated machines that “endlessly print roll upon roll of prayers” — has been omitted. Likewise, the movie omits a scene in which a fleeing Offred, her husband and their little girl have to abandon the family cat.

In fairness, the movie’s credits should have read “loosely adapted from a screenplay by Harold Pinter” while acknowledging Atwood and everyone else who contributed to the final result. One can only speculate whether a more faithful rendition of Pinter’s screenplay would have resulted in a superior film. In the meantime, we can be grateful that this original Pinter draft still exists.

Out of stock

![[Doyle, Arthur Conan (source work)]: "SHERLOCK HOLMES FIGHTS BACK" [released as: SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE SECRET WEAPON] 22 May - 17 June 1942](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/SherlockHolmesFightsBack-Script1-270x362.jpg)