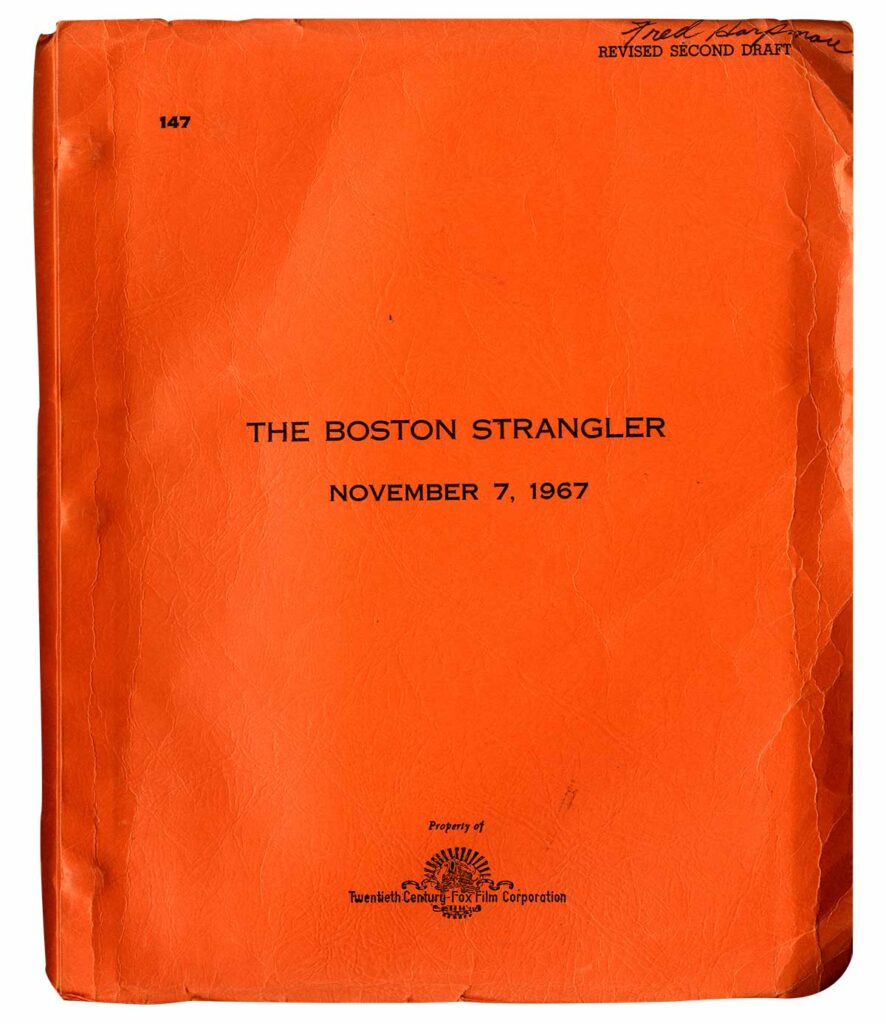

BOSTON STRANGLER, THE (Nov 7, 1967) Revised 2nd Draft screenplay by Edward Anhalt

With revised blue pages dated 11/14/67. Hollywood: Twentieth Century Fox, 1967. Printed wrappers, mimeograph, brad bound, quarto, minor creasing to yapped edges of wrappers, just about fine in very good+ wrappers. Script has name of Fred Harpman of the art department, who received a credit for production film treatment, and who left a drawing on the page facing page 95.

THE BOSTON STRANGLER is the third in a series of four films based on true crimes directed by genre chameleon Richard Fleischer (1916-2006). The other three in the series were THE GIRL IN THE RED VELVET SWING (1955), COMPULSION (1959) and 10 RILLINGTON PLACE (1971). THE BOSTON STRANGLER was clearly the most ambitious of the group, both from a narrative perspective and in terms of its radically experimental multi-screen visual style. Controversial in its day, Fleischer’s film is now considered a classic of ’60s neo-noir.

New York City-born screenwriter Edward Anhalt (1914-2000) co-authored with his wife, Edna Anhalt, the screenplays for PANIC IN THE STREETS (Elia Kazan, 1950), for which they received an Academy Award, MEMBER OF THE WEDDING (Fred Zinneman, 1952), and THE SNIPER (Edward Dmytryk, 1952). After his divorce from Edna, Edward Anhalt continued writing screenplays – many of them adaptations – for films like THE YOUNG LIONS (Dmytryk, 1958), BECKET (Peter Glenville, 1964), for which he received another Academy Award, and JEREMIAH JOHNSON (Sydney Pollack, 1972). He agreed to write the screenplay for THE BOSTON STRANGLER, based on Gerold Frank’s book, after an unsuccessful effort by British playwright Terence Rattigan.

Tony Curtis received a Best Actor Golden Globe nomination for his portrayal of the title role, a subtle and committed performance unlike anything the actor had previously done, while Anhalt was nominated for an Edgar Allen Poe Award by the Mystery Writers of America for his screenplay.

Anhalt’s script paints a picture of the crimes and the way the way they were investigated through a brilliant accumulation of details. Consider the way his screenplay opens:

INT. ANNA SLESERS’ APARTMENT – BOSTON – DAY

We are watching a TV picture of ALAN SHEPARD’S welcome to Boston. We SEE the crowds on the Common; Shepard on the back of a limousine waves and a military band plays brassily. Applause ripples along the street, flags flutter in the mild breeze. It is a cheerful scene. We MOVE BACK. The television set is in the corner of the living room.

Suddenly our view is disturbed by the contents of a woman’s purse emptied before us. Then, in quick succession, the gloved hands that hold the purse dump out the contents of a bureau drawer, a kitchen drawer, a living room table drawer, and finally a waste basket.

We MOVE from the torn paper on the floor to a crooked bare knee in the f.g. Then we SEE the thigh and then through the space between the two, the other bare leg …

What Anhalt’s screenplay doesn’t indicate is the way director Fleischer chose to shoot this material. As previously mentioned, Fleischer developed an innovative multi-screen technique for shooting this movie, dividing the widescreen motion picture frame into sub-frames that appear, disappear, and change shape – at some points in the narrative dividing the overall frame into as many as seven separate images. For example, in the scene described above, the image of the tv screen occupies the tiny upper left hand corner of the frame surrounded by black. Then the frame opens up to show the entire apartment, the camera pulling back to finally show the killer’s legs crossing left to right. The various details – the killer’s gloved hands rifling through a bureau drawer, then the kitchen drawer, then a living room table drawer, then the victim’s record collection, etc. – are each given a separate image that occupies a different portion of the overall frame. Fleischer and his cameraman, Richard Kline, shoot the entire film in this manner, all of it carefully storyboarded ahead of time. The film’s sound design is equally intricate. Although Anhalt’s script balances multiple perspectives – killer, victims, investigators, suspects, media, witnesses, and concerned citizens – no one merely reading the screenplay could anticipate what Fleischer would do with it.

Fleisher’s multi-screen technique accomplishes several things. It creates a sense of complexity, of multiple events happening separately and simultaneously, of the many details and points of view that will become important during the course of the investigation, and – most importantly – the sense of an entire city in crisis, and the many individual lives caught up in the chaos.

Apart from the application of Fleischer’s technique, there were other significant changes between this Revised Second Draft screenplay and what was ultimately shot. Some scenes, lines, and characters were tweaked or removed, and others were added. The names of some characters were changed, e.g., the name of the police detective played by George Kennedy was changed from Lt. Joseph Corsi in the screenplay to Lt. Phil DiNatale in the film. The order of scenes was rearranged.

The film’s protagonist, Joseph Bottomly (Henry Fonda), a Harvard academic who coordinates the investigation, is not introduced until approximately one third of the way through the narrative. We do not see the face of the killer, Albert DeSalvo (Tony Curtis), until the movie’s second half (page 92 of the screenplay). Although most of the screenplay and film is intensely realistic, the style turns expressionistic after the killer is finally identified and apprehended and, as he undergoes hypnosis, we see events replayed from his deranged point of view.

This is a boundary-pushing screenplay and film. Sex crimes and the ways they are committed are openly discussed. The film has significant LGBTQ content. Bottomly interviews a lesbian couple in their upscale Boston apartment. They direct him to an elegant suspect, played by THE PICTURE OF DORIAN GRAY’s Hurd Hatfield, whom he interviews in a gay bar.

As audacious in its subject matter as it is technically avant-garde, THE BOSTON STRANGLER could be called the CITIZEN KANE of true crime films, and just as Herman Mankiewicz’s screenplay was an essential element of what Orson Welles achieved with KANE, Edward Anhalt’s meticulous screenplay was essential to what director Richard Fleischer achieved in the 1960s with THE BOSTON STRANGLER.

Out of stock

![ESCAPADE [working title for: A WARM DECEMBER] (Jun 11, 1971) Revised First Draft screenplay](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/EscapadeSCR_a-270x348.jpg)

![[Doyle, Arthur Conan (source work)]: "SHERLOCK HOLMES FIGHTS BACK" [released as: SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE SECRET WEAPON] 22 May - 17 June 1942](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/SherlockHolmesFightsBack-Script1-270x362.jpg)