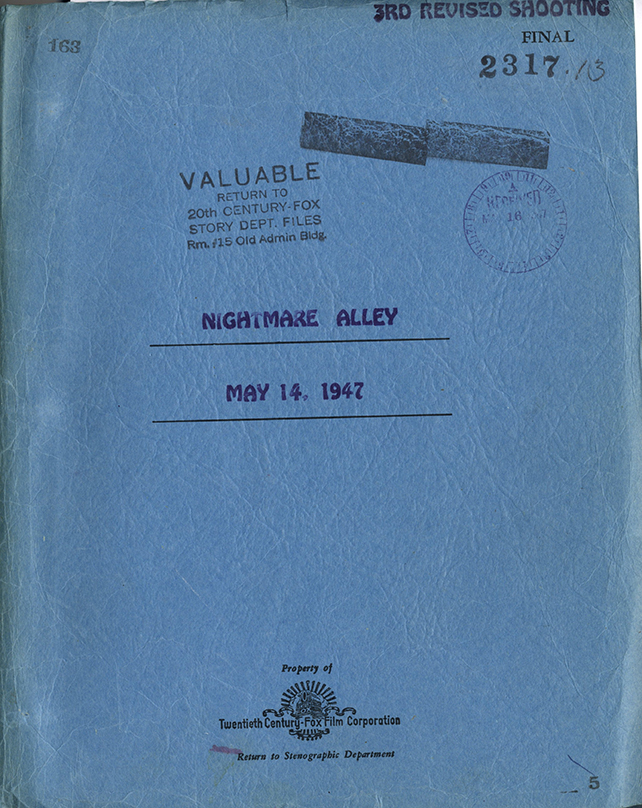

NIGHTMARE ALLEY (1947) Vintage original film script

“Screenplay by Jules Furthman Based on the novel by William Lindsay Gresham 3rd Revised Shooting Final May 14, 1947.”

Corrective notation in holograph pencil on the title page, and brief notations in holograph pencil on the versos of a few pages. Studio File Copy, rubber-stamped on the front wrapper.

Based on Gresham’s 1946 novel, a dispassionate descent into the world of the carnival sideshows, based largely on the author’s own experiences and investigations. Tyrone Power plays against type as a devious swindler who works his way from a traveling carnival to high society, only to inevitably fall down again.

Filmed with a larger budget than most film noirs due to Power’s stardom, the film was initially a flop but has since become regarded as a classic of the genre.

Blue titled wrappers, noted as 3RD REVISED SHOOTING FINAL on the front wrapper, rubber-stamped copy No. 5 and 163, dated May 14, 1947. Distribution page not present. Title page present, dated May 14, 1947, noted as 3rd Revised Shooting Final, with credits for screenwriter Furthman and novelist Gresham. 168 leaves, with last leaf of text an unnumbered revision page. Mimeograph, with blue and green revision pages throughout, dated variously between 5/20/47 and 8/9/47. NEAR FINE in VERY GOOD+ wrappers, brad bound.

Jules Furthman (1888-1966) was one of the greatest screenwriters of Hollywood’s golden era, best known for the movies he wrote or co-wrote for directors Joseph von Sternberg (THE DOCKS OF NEW YORK, THUNDERBOLT, MOROCCO, SHANGHAI EXPRESS, THE SHANGHAI GESTURE) and Howard Hawks (ONLY ANGELS HAVE WINGS, TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT, THE BIG SLEEP, RIO BRAVO). His screen adaptation of NIGHTMARE ALLEY, William Lindsay Gresham’s best-selling novel about the rise and fall of a carnival huckster and phony spiritualist, was arguably Furthman’s most challenging assignment.

A genuinely faithful adaptation of the novel would have the gritty, sordid feeling of Tod Browning’s FREAKS (1933). Instead, with Edmund Goulding directing, and Lee Garmes as cinematographer, the movie version has the shadowy glossiness of a Twentieth Century Fox film noir, which in fact it is.

This was the second consecutive film, following THE RAZOR’S EDGE (1946), made by star Tyrone Power with director Goulding in an attempt to change Power’s image from romantic leading man to serious actor. For audiences who were familiar with Power, his unsavory NIGHTMARE ALLEY performance was a revelation and a shock.

Screenwriter Furthman’s challenge was to take the most controversial and unfilmable aspects of Gresham’s novel – having to do with sex, politics, and religion – and adapt them in a way that would be acceptable to the Hollywood Production Code of his day while at the same time retaining the novel’s harrowing essence. Moreover, studio head Darryl F. Zanuck insisted that the movie should have a “redemptive” ending. Notwithstanding all of these obstacles, Furthman’s screenplay is brilliant, and the film has become a cult classic.

Differences between Novel, Shooting Script, and Film

There are only minor changes between this shooting script and the released film, most of them involving the trimming of dialogue and business, e.g., in the early carnival sequences, a bit where Zeena the fortune teller (Joan Blondell) corrects Stan’s (Tyrone Power’s) grammar, and a brief deleted scene where Zeena has to stop her act prematurely because her alcoholic husband Pete, who is hidden underneath the stage to feed her information, has passed out.

The most substantial changes are between the novel and the screenplay. For example, in the novel, Stan, who covets Zeena and her act, kills the alcoholic Pete deliberately by giving him a bottle of poisonous wood alcohol instead of bathtub gin. In the screenplay and film, Stan gives Pete the wood alcohol accidentally due to the fact the two bottles look alike. Surely, this change was made to make Power’s character a little more sympathetic to film audiences. Yet, at the same time, it is consistent with the screenplay’s characterization of Stan as a man driven as much by unconscious forces as by motivations he understands.

Most of the real carnival freaks who are in the novel have been omitted from Furthman’s screenplay. Major Mosquito, a midget, appears briefly in the shooting script, but is omitted from the completed film, his lines given to a full-sized performer. The movie, even more than the book, suggests that con-artist Stan’s psychic abilities are not entirely fake. However, both the book and the movie believe firmly in the power of Zeena’s Tarot cards to predict a mostly ominous future. (The book is structured like a Tarot deck, featuring a different Major Arcana card for each of its 22 chapters.) It is the fatalism of the book and the film, more than any other factor, that situates them in the world of noir.

The book, screenplay, and film chart Stan the con-artist’s climb from carny fortune telling to nightclub mentalism to a high-priced phony spiritualism designed to fleece the rich. However, in the book, Stan’s spiritualism is cloaked with fake Christianity. He calls himself a Reverend, wears a minister’s collar, and laces his act with quotes from the Bible. The screenplay and the movie eliminate virtually all specific references to Christianity and the Bible.

Stan’s decline begins when he meets Dr. Lilith Ritter (played by Helen Walker in the movie) the manipulative psychotherapist who ultimately out-cons him, playing on his insecurities. In the book, Lilith is an outright dominatrix who subdues a sexually aggressive Stan with a judo flip and later compels him to kneel at her feet painting her toenails. In the shooting script and movie, none of this is overtly expressed, but communicated sub-textually through dialogue, costuming (she dresses androgynously), and performance.

Gresham’s book was very sensitive to issues of race and class. (Gresham himself was a Communist who fought in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.) As you might expect, very little of this makes it into the shooting script or completed film. For example, one of the novel’s scenes in which rail-riding Stan shares a boxcar with a black labor organizer is completely omitted.

The fatalism of book and film are most apparent in their treatment of the “geek,” a degraded carnival performer who bites the heads off live chickens in exchange for a daily bottle of booze and a place to sleep. Stan’s fascination with the geek in the story’s opening scenes telegraphs his ultimate destiny as a geek himself. The book ends with alcoholic Stan, who can sink no lower, accepting the geek job. The screenplay and film follow his degradation as a geek even further, including a night scene in which Stan runs amuck with the screaming horrors.

However, because studio head Zanuck ordered it, the shooting script adds a coda (blue pages dated 6/14/47) in which Stan is rescued by good girl Molly (Colleen Gray).

And finally, there is a coda to the coda (green page dated 8/9/47) in which two carnival workers spell out the moral of the story. “YOUNG MAN: Hey, Boss – how does a guy get so low? McGRAW: He reached too high ….”

Grant US. Selby US Masterwork. Silver and Ward Classic Noir. Spicer US. Weldon 1983.

Out of stock

![[Doyle, Arthur Conan (source work)]: "SHERLOCK HOLMES FIGHTS BACK" [released as: SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE SECRET WEAPON] 22 May - 17 June 1942](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/SherlockHolmesFightsBack-Script1-270x362.jpg)