GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS (1992) First draft screenplay by David Mamet

David Mamet (source, screenwriter). Los Angeles: Zupnik Enterprises, [1991]. Vintage original film script, printed wrappers of the film’s production company, Zupnik Enterprises, 126 pp., a clean, first-generation script with no copied punch holes, fine in near fine wrappers.

David Mamet’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play Glengarry Glen Ross, and the first draft screenplay he wrote based on it, both begin in a Chinese restaurant. In the two-act play, the entirety of the first act takes place in the Chinese restaurant, and the entirety of the second act takes place in a real estate office. However, in the screenplay the action moves rapidly from the Chinese restaurant to a men’s room to a bar to the real estate office within the first 8 pages.

Although there is nothing in Mamet’s screenplay that couldn’t be presented on a stage, Mamet’s screenplay (for which he got paid a total of $1 million, including rights to the play) is a radical restructuring and improvement of his stage drama.

Both works, play and screenplay, are all-male ensemble dramas, although we do briefly see one woman in the film’s first Chinese restaurant scene, a coat check girl who asks one of the exiting salesmen, “Slow tonight?” All the other female characters, including the sick daughter of Shelly Levene (Jack Lemmon), and the wives of a couple of the sales customers are referred to in dialogue but never actually seen on stage or on-screen.

There are eight principal on-screen characters: four real estate salesmen — Levene (Lemmon), Roma (Al Pacino), Moss (Ed Harris), and Aaronow (Alan Arkin) — a weaselly office manager (Kevin Spacey), a hapless customer (Jonathan Pryce), and a cop. The eighth character — who Mamet created especially for the film — is a representative from the main office, Blake (Alec Baldwin), who arrives to give the salesmen a “pep talk” consisting of nothing, basically, but verbal abuse:

MOSS

What’s your name?

BLAKE

Fuck you, that’s my name. You know why, Mister? ‘Cause you drove a Honda to get here tonight, I drove a sixty-thousand dollar B.M.W. That’s my name, and your name is you’re wanting …

(Underlining in original)

The Blake/Alec Baldwin scene is critical to the film version, because it effectively establishes the film early-on as an ensemble piece, with all the salesmen (but one), the office manager, and the company representative present together in the same real estate office. By way of contrast, the play’s first half, set in a Chinese restaurant, consists of three two-man scenes — Scene One, Levene and Williamson; Scene Two, Aaronow and Moss; Scene Three, Roma and Lingk (the customer) — and does not have the same ensemble feeling. The Blake/Alec Baldwin scene is also critical insofar as it heightens the main characters’ motivation for the remainder of the film. Blake tells the salesmen they are in a contest for the next sales period — First Prize is a Cadillac; Second Prize is a set of steak knives; and the prize for everyone else is, “You’re fired.”

Speaking of motivation, the film — unlike the play — opens with a scene where Levene (Lemmon) is on the phone with a hospital inquiring about the condition of his daughter: he’s going to need a lot of money for an operation. This makes Lemmon’s desperate character, essentially a fraud and a swindler, at least a little more sympathetic and understandable as far as the movie audience is concerned.

The film also benefits from a change in setting. The play is set in Chicago; the movie is set in New York; and director James Foley elected to stage a number of scenes outdoors at night in the rain. This gives the movie a strong film noir atmosphere which is augmented by the film’s lighting and production design, inspired by the paintings of Edward Hopper.

In short, the film improves on the play with shorter scenes, a wider variety of locations, a rich film noir atmosphere, and more scenes where we see the characters as a group — not to mention a once-in-a-lifetime ensemble cast.

Regardless, the heart of GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS, play and film, is its language, a particularly David Mamet style of language (which owes a little bit to Harold Pinter, another distinctively language-oriented dramatist to whom the play is dedicated). The dialogue of Mamet’s characters is alternately (even within the same speech) wheedling and threatening, insulting and cajoling, proud and craven, circuitous and blunt, veering from double talk to profanity (lots of profanity), hilarious in a black comic way, sometimes offensive, but never dull. Mamet’s GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS screenplay represents one of America’s most important playwrights and screenwriters at his absolute best.

Out of stock

Related products

-

SLEEP ON THE ROOF (1967) Unproduced script based on the life of Margaret Sanger

$500.00 Add to cart -

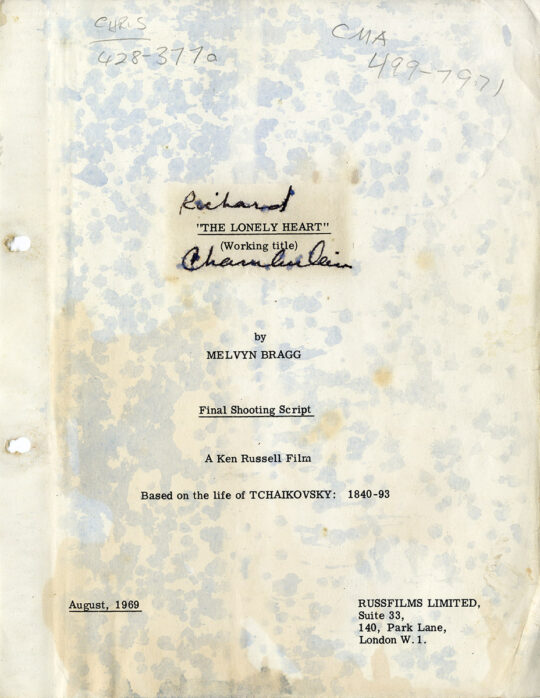

Ken Russell (director) THE MUSIC LOVERS [working title: THE LONELY HEART] (1969) Final shooting script

$3,000.00 Add to cart -

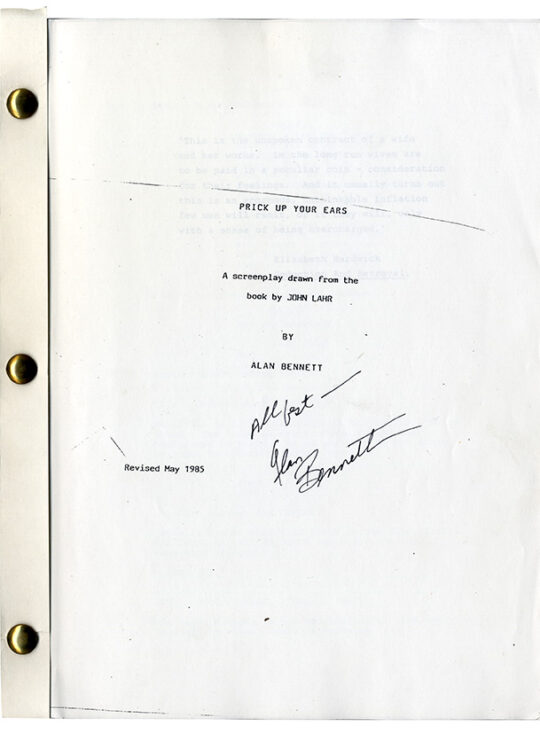

PRICK UP YOUR EARS (May 1985) Revised film script

$650.00 Add to cart -

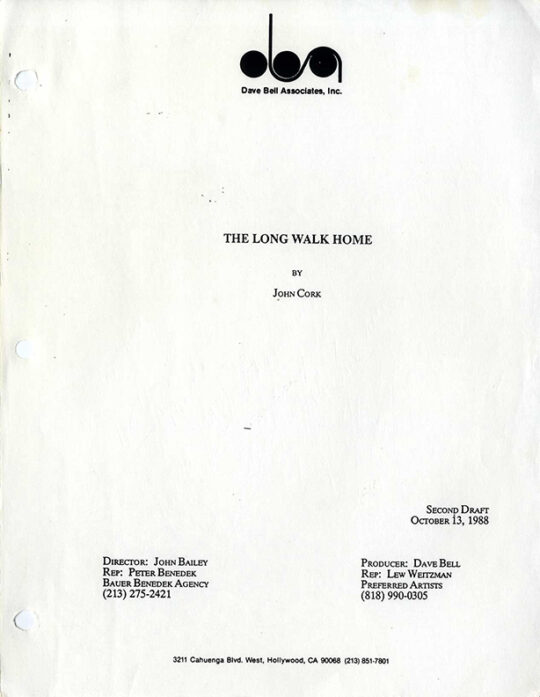

LONG WALK HOME, THE (Oct 13, 1988) Second draft film script by John Cork

$375.00 Add to cart