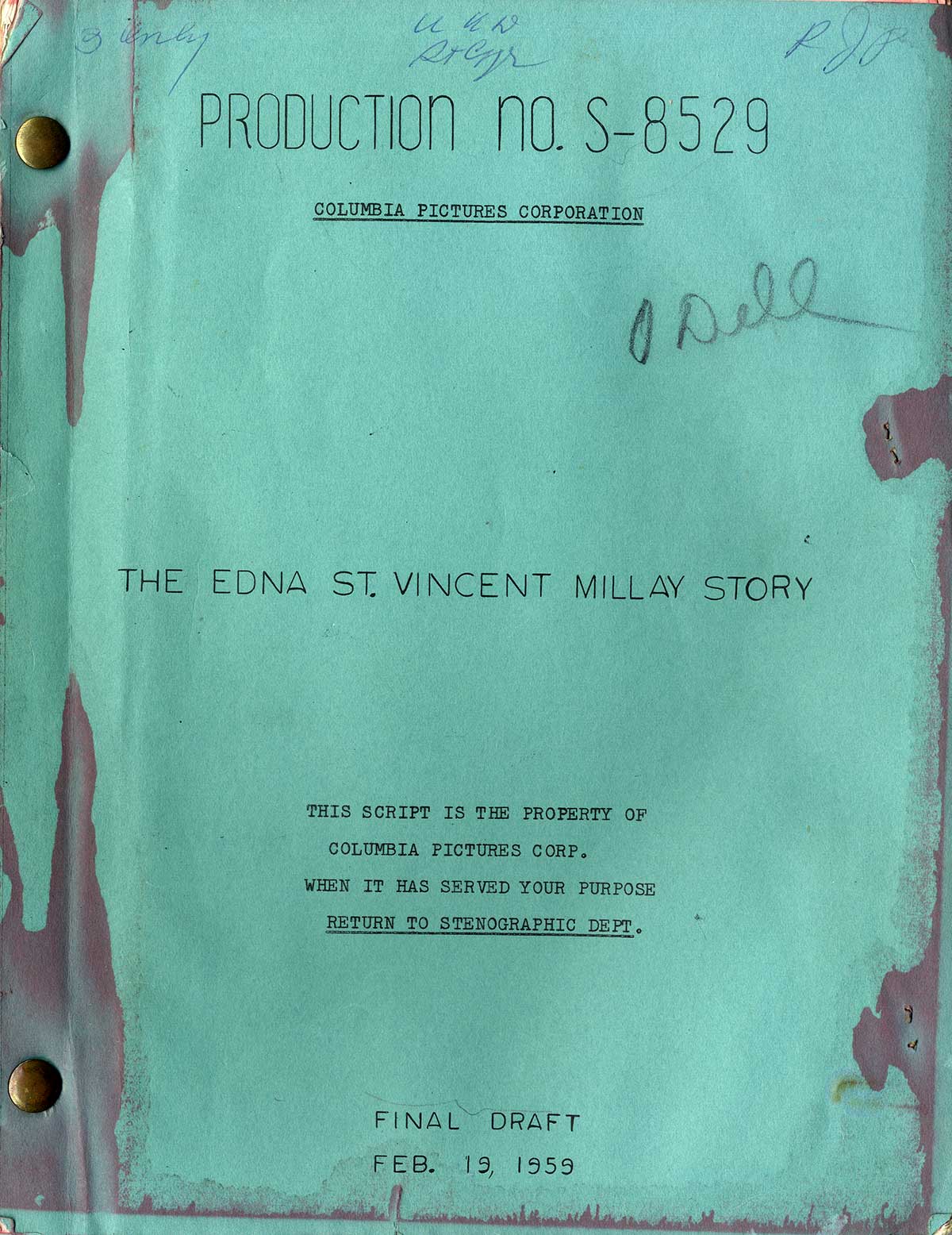

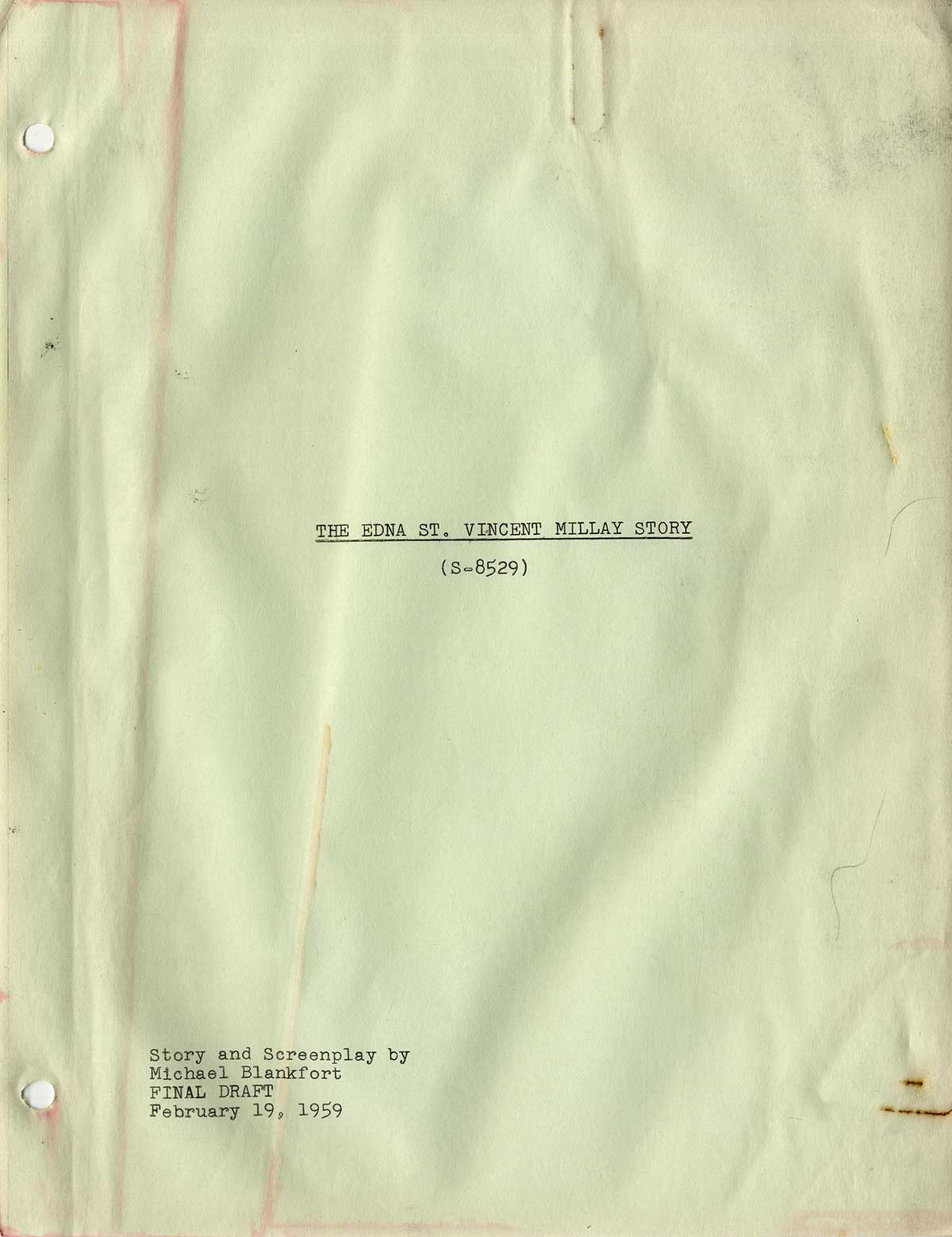

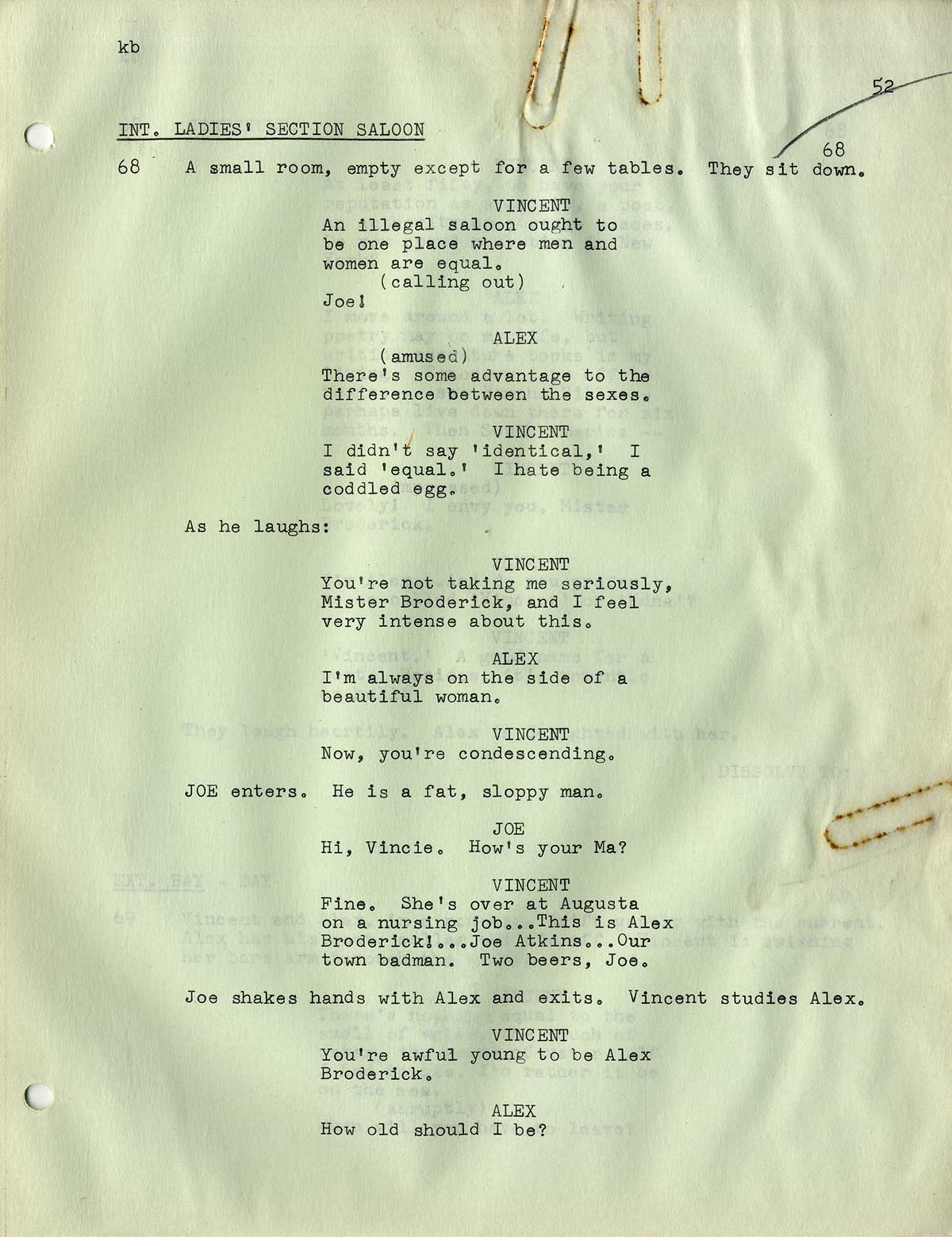

EDNA ST. VINCENT MILLAY STORY, THE (Feb 19, 1959) Final Draft screenplay by Michael Blankfort

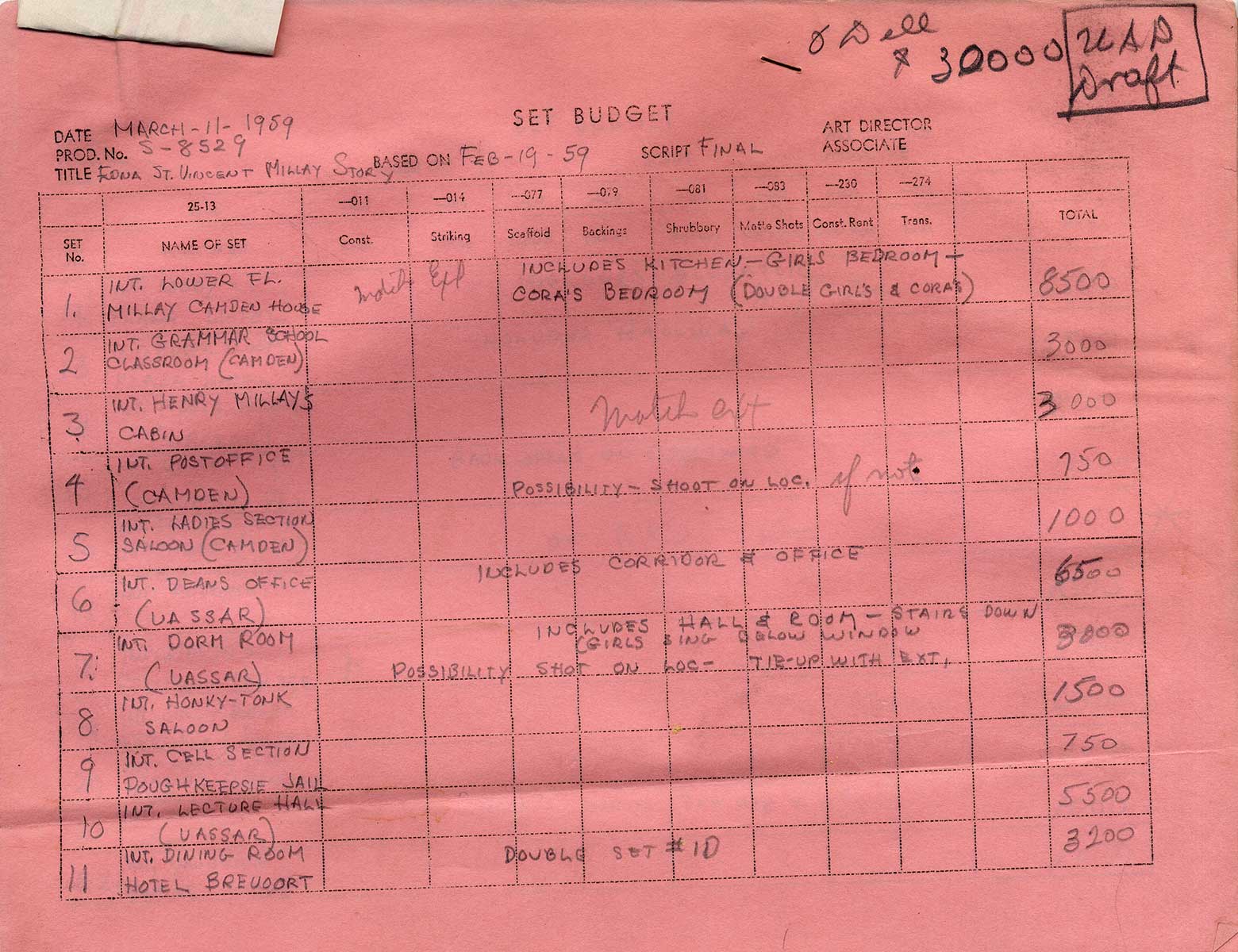

Yellow revised pages dated September 3, 1959. Hollywood: Columbia Pictures, 1959. Vintage original script. Printed wrappers, 157 pp. Quarto, brad bound, mimeograph, 7 pp. budget attached on pink paper. Stains to front cover, many pages have rust marks where paper clips were once attached, overall GOOD-, but a solid reading copy.

[sold with]:

10 pp., consisting of 3 one-page typed letters, and a 7 pp. letter on carbon paper, with MS corrections, from the files of producer Raymond Stross, who was working on developing this script for a film starring his wife Anne Heywood.

Jewish-American playwright and screenwriter Michael Seymour Blankfort (1907-1982) might be best known as the “front” for blacklisted Albert Maltz on the Academy Award-nominated screenplay of BROKEN ARROW (Delmar Daves, 1950), but he also wrote or co-wrote several significant screenplays himself, including THE DARK PAST (Rudolph Maté, 1948), MY SIX CONVICTS (Hugo Fregonese, 1952), THE JUGGLER (Edward Dmytryk, 1953 – based on Blankfort’s own novel), THE CAINE MUTINY (Dmytryk, 1954), and TRIBUTE TO A BAD MAN (Robert Wise, 1956).

Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and playwright Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950) might seem an unlikely subject for a Hollywood biopic, but as a free-spirited Jazz Age icon known for her feminism and, later, her anti-fascism, her life provided ample material for a screenplay. She sold 50,000 copies of a book of poems in the midst of the Great Depression, yet died a reclusive alcoholic morphine addict. This ambitious story of her life was, in fact, budgeted by Columbia Pictures, but ultimately never produced.

Blankfort’s screenwriting is vivid and visual. Consider the way his Millay screenplay opens:

“A SERIES OF ESTABLISHING SHOTS OF CAMDEN MAINE, showing the romantic, yet respectable character of a moonlit New England town at the turn of the century… Through a warmly lit window we hear the tinkling of a parlor piano; and from another house the deeper wheeze of a parlor organ… A TITLE says: 1905. Finally, the CAMERA MOVES to a darker, meaner street. Suddenly, the door of a house is flung open, a man is outlined by the glow of a lamp from within. He throws a whiskey bottle against some rocks. The crash of the glass frightens some birds and they whir past camera. After an unsteady moment, the man re-enters his house, closing the door behind him.”

Blankfort’s screenplay dramatizes the life of Edna St. Vincent Millay – generally called “Vincent” by her family and friends – from the age of 12 when her supportive mother, Cora, ejects Vincent’s alcoholic abusive father from their Maine home, until her mid-forties when she is a living legend.

We see her as a rebellious adolescent, submitting her first work to poetry magazines, and as a 20-something, having won a scholarship to New England’s Vassar College. In this portion of the screenplay, she is written like an ingénue heroine out of Thornton Wilder or William Inge, or maybe Jo from Little Women. In the screenplay’s longest section, she is a Bohemian artist living in Greenwich Village, a successful poetess and playwright who becomes part of Eugene O’Neill’s avant-garde theater group, the Provincetown Players.

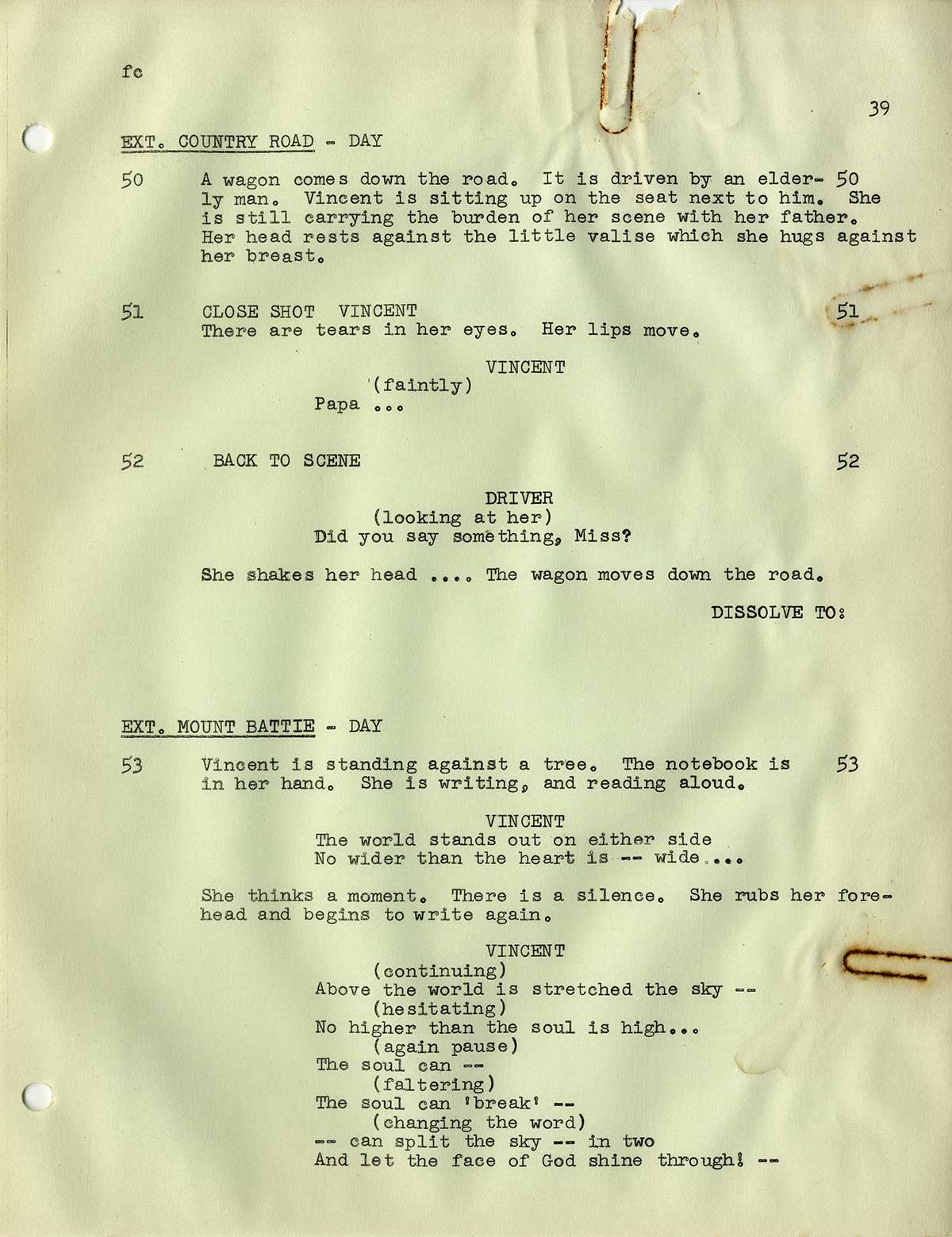

The most difficult thing to dramatize in a writer’s life is the writing itself. Blankfort’s screenplay accomplishes this by quoting some of Millay’s best known lines in the context of the moments that might have inspired them. For example:

SHOT OF VINCENT

She is crumpled up on the rock, her legs drawn up tight against her body. She is weeping. Slowly, she looks up. In the b.g. are the mountains. After a moment:

VINCENT

(sadly)

All I could see from where I stood

Was three long mountains and a wood; —

She rises and looks off to the bay in the b.g.

VINCENT

I turned – and looked another way

And saw three islands in a bay…

Much of the screenplay is concerned with a romantic triangle, showing Vincent torn between her true love, a romantic world-traveling journalist, Alex Bertrand (a fictionalized composite character), and the reliable businessman who was Millay’s husband in real life, Eugene “Gene” Boissevain.

In real life, Millay was bisexual, but this is not something a Hollywood screenplay written in 1959 was likely to address. Nor her health problems arising from an abortion. It does not dramatize her painful final years living in rural Austerlitz, New York.

Instead, Blankfort’s screenplay ends on a note of nostalgia, with 40-something Vincent and her husband, Gene, visiting their old haunts in Greenwich Village, including the café where she used to hang out with the likes of Eugene O’Neill, Maxwell Bodenheim, and John Reed, and as the couple passes under a streetlamp, they hear the voice of a young man reciting Millay to his girlfriend:

YOUNG MAN

(softly)

‘Above the world is stretched the sky

No higher than the soul is high;’ –

The soul can split the sky in two,

And let the face of God shine through!’

Out of stock

Related products

-

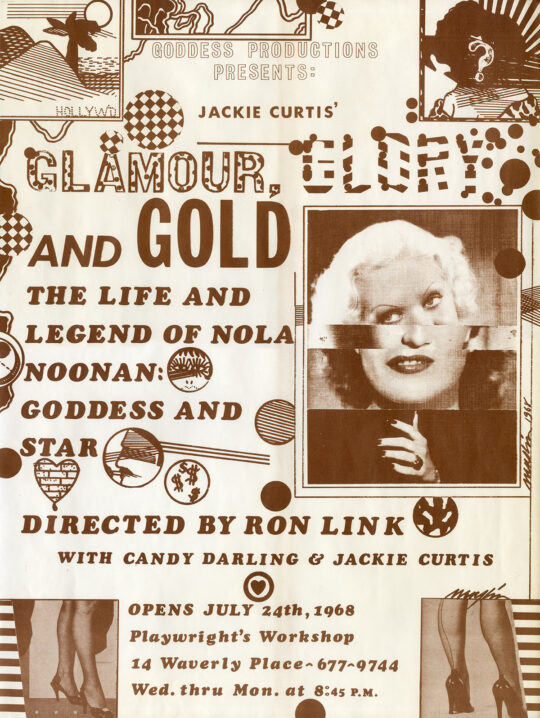

GLAMOUR, GLORY AND GOLD: THE LIFE & LEGEND OF NOLA NOONAN, GODDESS & STAR (1968) Theatre poster

$500.00 Add to cart -

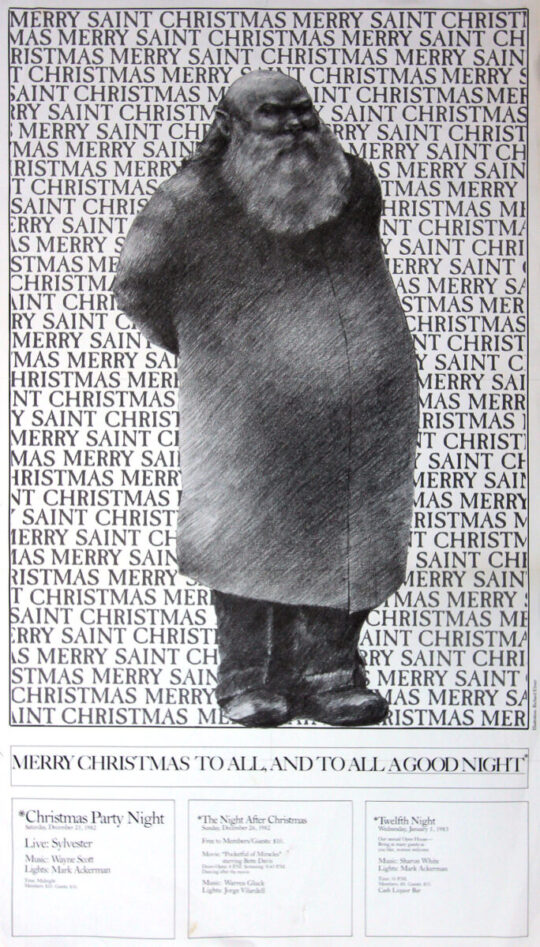

MERRY SAINT CHRISTMAS (3 events incl. CHRISTMAS PARTY ft. Sylvester live) (Dec 25, 1982) Event poster for The Saint

$200.00 Add to cart -

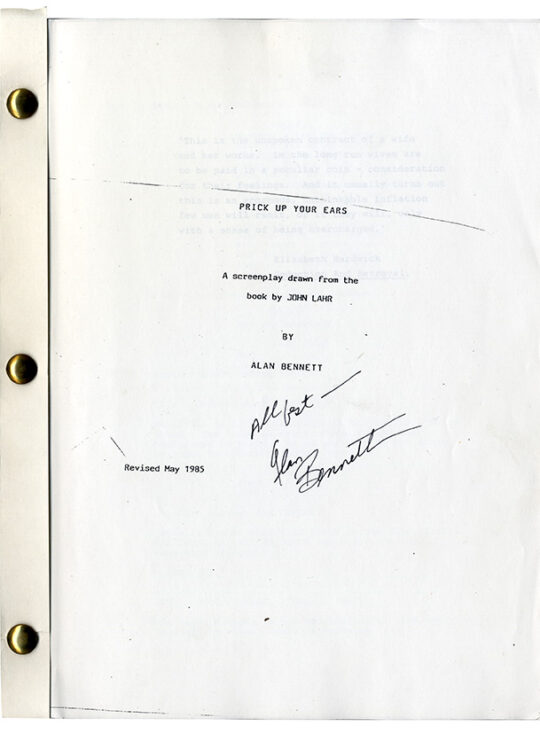

PRICK UP YOUR EARS (May 1985) Revised film script signed by screenwriter

$650.00 Add to cart -

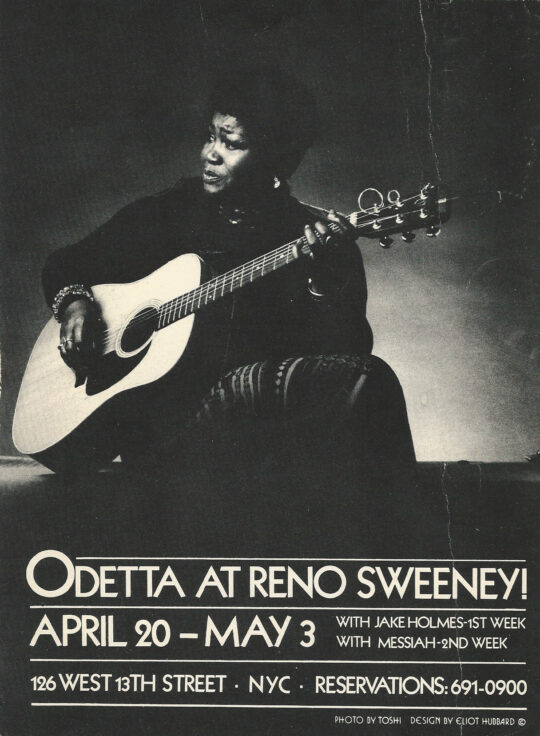

ODETTA at RENO SWEENEY (1975) Postcard

$100.00 Add to cart