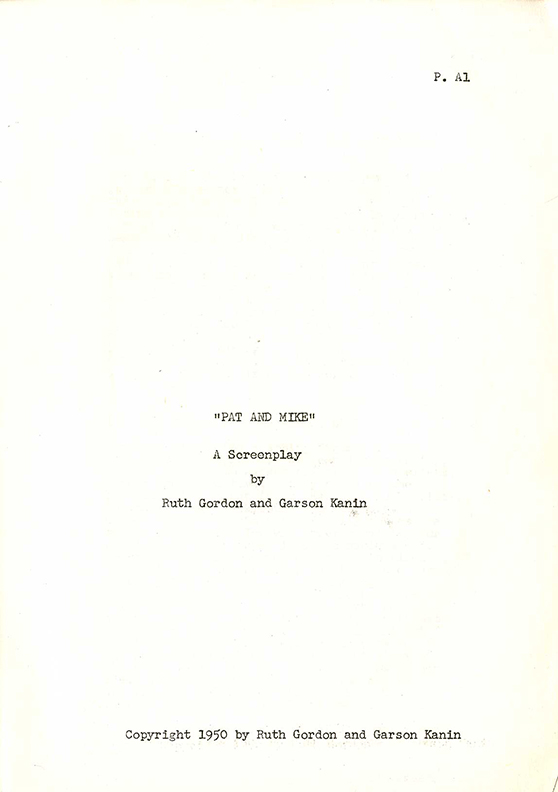

PAT AND MIKE (Jun 6, 1951) Film script by Ruth Gordon, Garson Kanin

Ruth Gordon, Garson Kanin (screenwriters) George Cukor (director) Vintage original film script, USA. Culver City: MGM, June 6, 1951. Quarto, printed wrappers, brad bound, mimeograph, chipping to blank back wrapper, 142 pp., overall near fine.

PAT AND MIKE was the second romantic comedy written for director George Cukor by the married screenwriting team of Ruth Gordon and Garson Kanin that was specifically tailored for its stars, Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy, who were friends of Gordon and Kanin. The first film written by Gordon and Kanin for the Cukor/Hepburn/Tracy team was the very successful ADAM’S RIB (1949) about a pair of married lawyers. Prior to that, Gordon and Kanin had written the screenplay for Cukor’s A DOUBLE LIFE (1947) starring Ronald Coleman as a contemporary actor who identifies too closely with Shakespeare’s Othello. All three of the Gordon/Kanin screenplays mentioned above received Academy Award nominations for Best Original Screenplay. With respect to PAT AND MIKE, Gordon and Kanin were inspired by Ms. Hepburn’s formidable athletic abilities, particularly with regard to golf and tennis, and the film was designed to show off those abilities, with Hepburn performing most of her own stunts.

Ruth Gordon (1896-1985) was a Jewish-American stage and film actress, as well as a screenwriter, most fondly remembered for the mischievous elderly women she played in ROSEMARY’S BABY (Roman Polanski, 1968), for which she received the Best Supporting Actress Oscar, and HAROLD AND MAUDE (Hal Ashby, 1971). After PAT AND MIKE, Gordon and Kanin co-wrote the screenplay for Cukor’s THE MARRYING KIND (1952), while Gordon received sole screenplay credit for writing Cukor’s THE ACTRESS (1953), based on her own autobiographical stage play Years Ago.

Garson Kanin (1912-1999) was a stage and film director, as well as a playwright and novelist, best known for his 1946 play Born Yesterday (filmed by George Cukor in 1950), and for directing the films, BACHELOR MOTHER (1939), MY FAVORITE WIFE (1940), THEY KNEW WHAT THEY WANTED (1940), and TOM, DICK AND HARRY (1941). He was married to Ruth Gordon from 1942 until her death in 1985.

While both ADAM’S RIB and PAT AND MIKE have strong feminist overtones, PAT AND MIKE is more overtly concerned with class. In PAT AND MIKE, the street-wise sports promoter played by Tracy is clearly not in the same social class as Hepburn’s upper-crust athlete, so much so that he doesn’t even consider having a romantic relationship with her until late in the film. PAT AND MIKE is also the more purely feminist of the two movies. ADAM’S RIB ends with Tracy putting Hepburn “in her place” (the usual outcome of most of the Hepburn/Tracy films), while at the end of PAT AND MIKE, the Hepburn and Tracy characters have achieved a relationship that is truly “50-50,” as Tracy’s character describes it, thanks to the pair’s shared enthusiasm for sports and their gradually learned mutual respect.

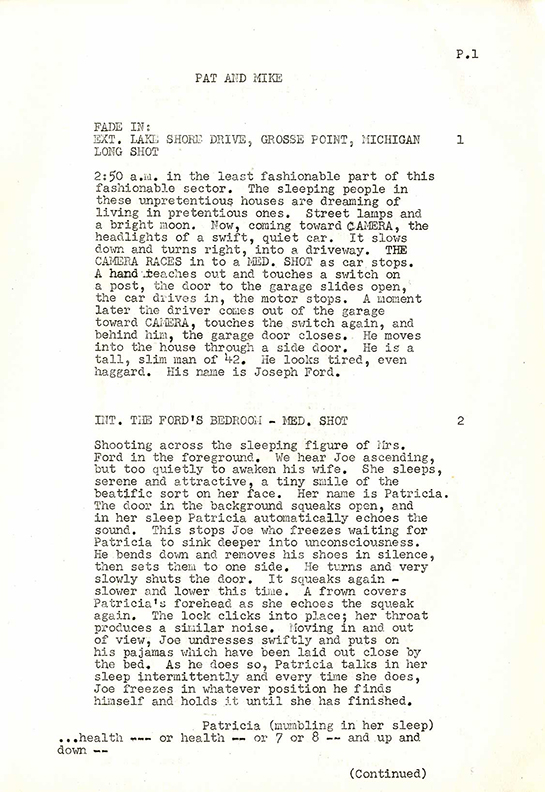

This particular draft of PAT AND MIKE is in some ways quite different from the completed movie. Both this draft and the completed film are structured around a romantic triangle consisting of Hepburn’s athlete, her significant other, and Tracy’s sports promoter, and in both versions Hepburn’s significant other is the major obstacle preventing her from reaching her full potential as an athlete and woman – until she dumps him and replaces him with the more understanding and supportive Tracy. However, the role of the significant other has been completely reimagined in the completed film. In this screenplay draft, the significant other is Hepburn’s husband named Joseph P. Ford, and he owns a car dealership, Consolidated Motors. In the movie, the significant other is Hepburn’s fiancé, he has an upper-crust name, Collier Weld, and he is the handsome but patronizing Assistant Administrator at a college where Hepburn (a widow) is working as a physical education instructor.

Consistent with the radical differences between the significant others in the screenplay draft and the film, the screenplay draft and the film have completely different openings. The screenplay draft opens with Hepburn and her businessman husband in their bedroom where the husband receives an important phone call from a client. The movie opens at a college where we see the fiancé leaving his administrative office to meet Hepburn’s character who we see instructing the girls in one of her phys. ed. classes.

After the disparate openings, the two versions follow comparatively similar paths. The second big scene in both versions is a couples golf game at a country club, where the husband/boyfriend insists that Hepburn win against her female opponent in order to impress a client/potential donor, and the husband/boyfriend’s patronizing presence, in fact, causes her to lose. After the game, the club’s bartender, who has seen her play outside the influence of her demeaning husband/boyfriend, tells her she has the potential to become a major professional athlete, and this precipitates the remainder of the story in which Hepburn acquires Tracy as her promoter and manager and, ultimately, her romantic partner. In both this draft and the completed film, Tracy’s character gets the movie’s most famous line (appraising Hepburn): “not much meat on her, but what there is is choice.”

This screenplay draft and the film also diverge radically in their final acts. The climax of the screenplay draft’s last act is the staging of a major public event in which women compete against men in various sports. The climax of the movie involves a trio of mobsters (including a young Charles Bronson) who are pressuring Tracy’s character to throw a game, and how Hepburn’s character rescues him when they are about to beat him to a pulp.

One of the screenplay’s conceits is that the audience will see Hepburn successfully playing professional golf and tennis alongside some of the major sports figures of the day, and the film does, indeed, feature such famous players as Babe Didrikson Zaharias (golf) and Don Budge (tennis). In the screenplay draft’s final scene, Hepburn is playing baseball with the great Joe DiMaggio and strikes him out! The movie, on the other hand, does not include the baseball scene and ends with an affirmation of the Tracy/Hepburn relationship, with her reversing roles and asking Tracy’s character the litany of questions that he beforehand routinely asked of all the players who were under contract to him, “Who made you? … Who owns the biggest piece of you? … What would happen if I dropped you?” Answer: “I’d go right down the drain.”

Out of stock

Related products

-

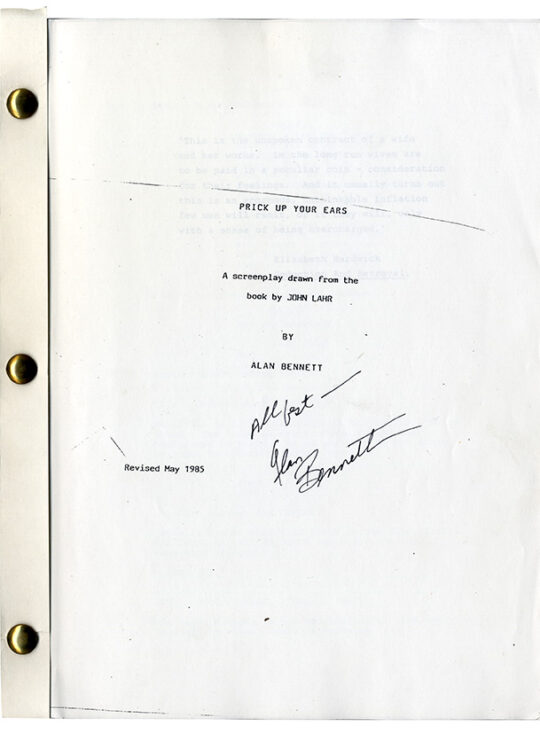

PRICK UP YOUR EARS (May 1985) Revised film script

$650.00 Add to cart -

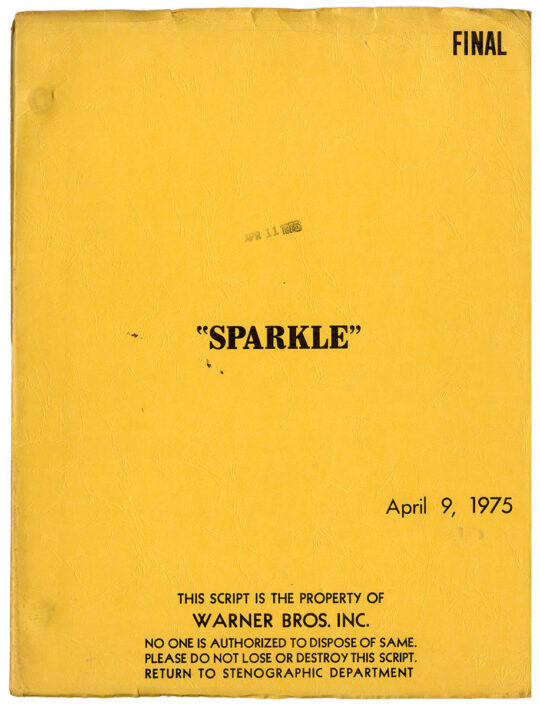

(Blaxploitation film) SPARKLE (Apr 9, 1975) Final Draft film script by Joel Schumacher

$750.00 Add to cart -

RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT, A (1987) Larry Cohen-signed script

$625.00 Add to cart -

CROSS CREEK (Feb 9, 1982) Rev Final Shooting script by Dalene Young

$750.00 Add to cart