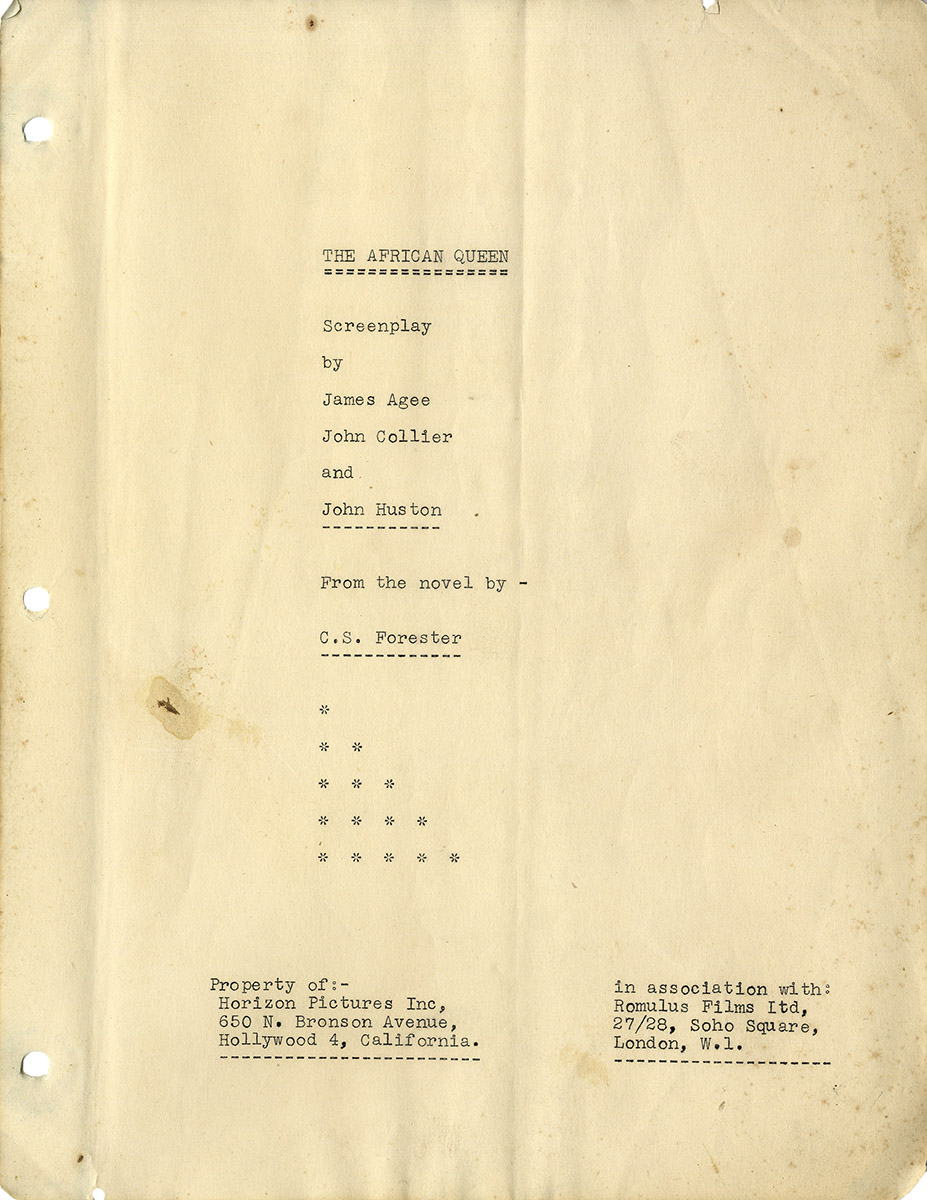

AFRICAN QUEEN, THE (1951) Screenplay by James Agee, John Collier and John Huston, From the novel by C. S. Forester

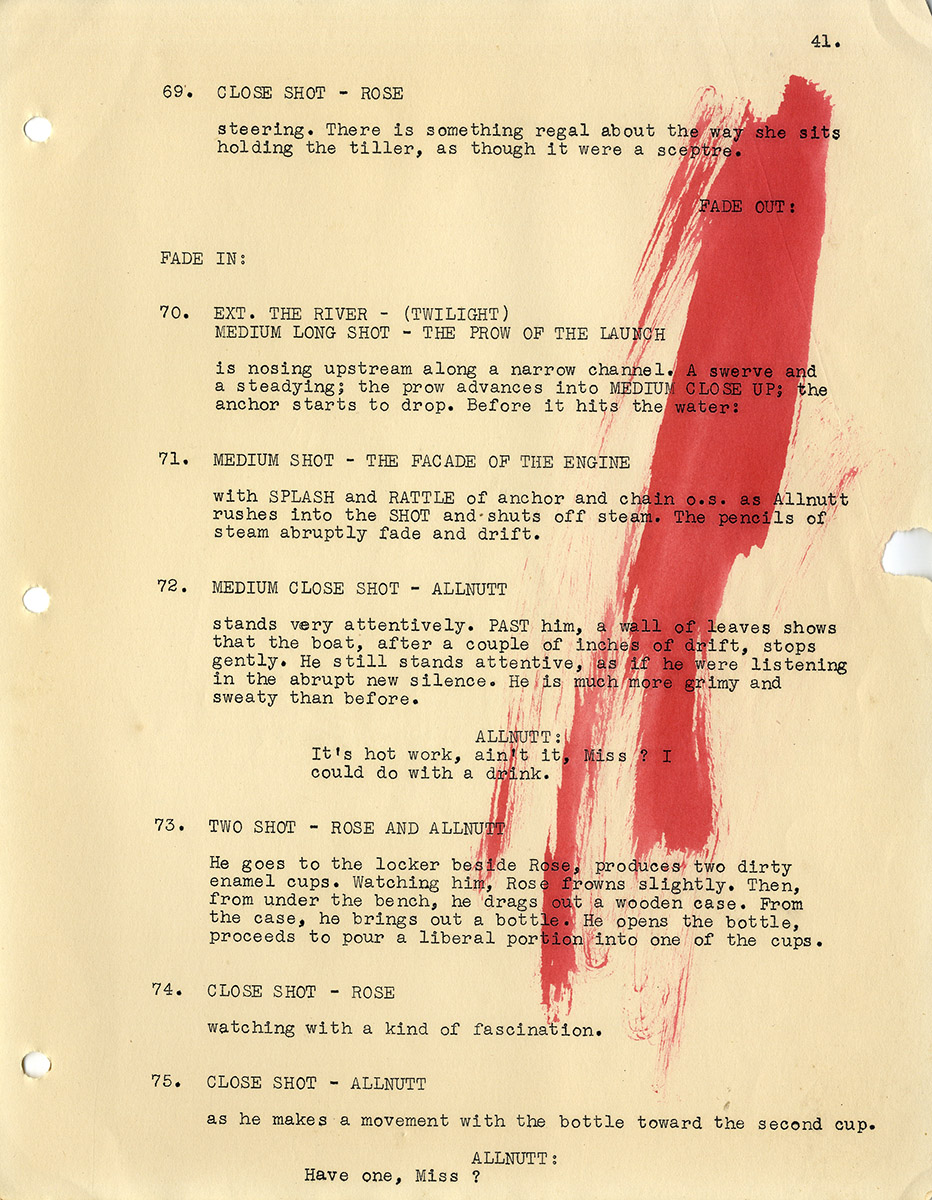

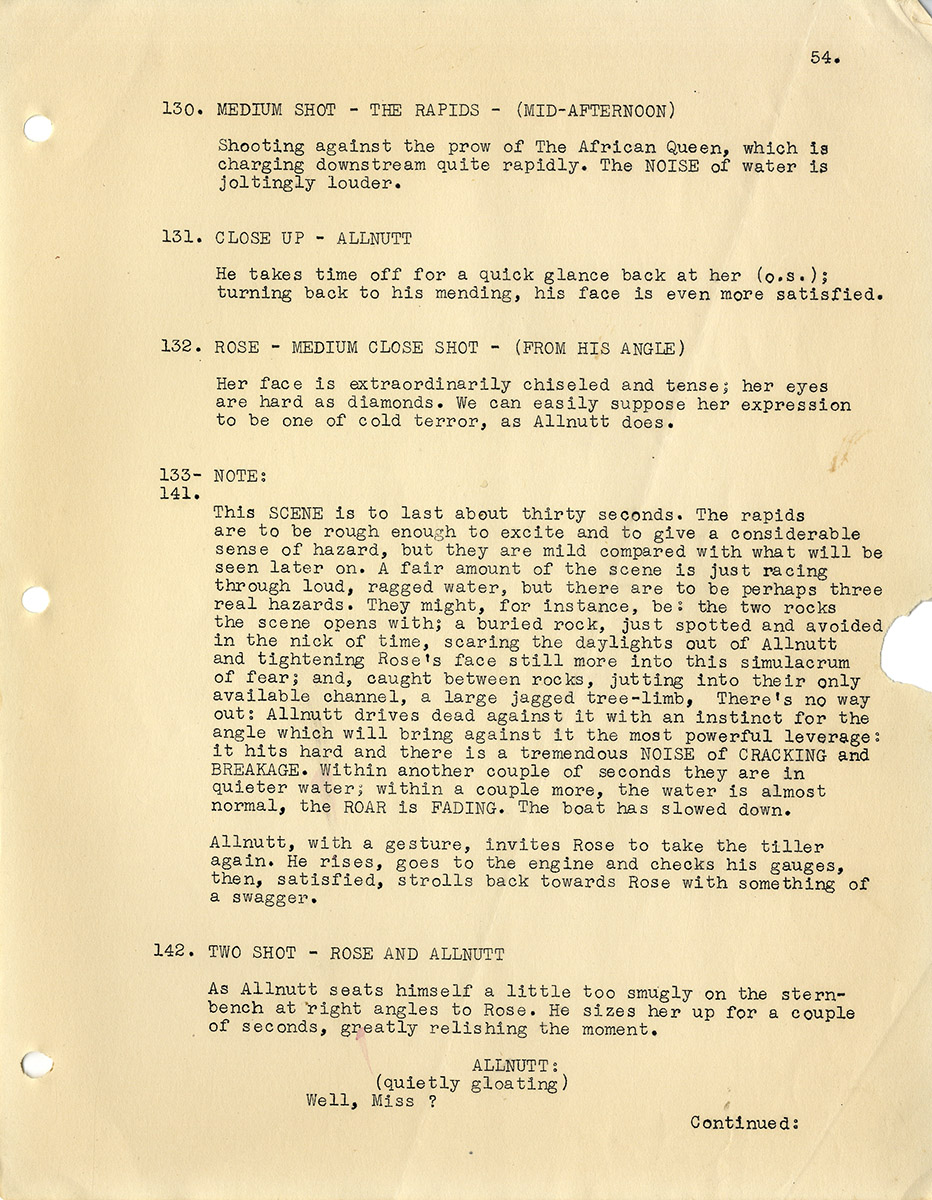

C. S. Forester (source) London: Romulus Films, [1951]. Vintage original film script, 11 x 8.5″ (28 x 22 cm.), 138 pp., brad-bound, plain wrappers (with a fragment of the original mimeographed label), mimeograph, many pages exhibit marginal chewing (not affecting any text), final page has a large blank area at bottom torn off, one page has paint stains, overall very good-.

Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and poet James Agee (1909-1955) was also considered one of the leading film critics of his era. In 1950 he wrote an admiring profile of director John Huston for Life Magazine (“Undirectable Director”) that is one of the first true auteurist studies published in the United States. Huston returned the compliment by inviting Agee to adapt the screenplay of C.S. Forester’s 1935 adventure novel, The African Queen.

The film that resulted, THE AFRICAN QUEEN, is one of the most honored movies of the 1950s. It earned Academy Award nominations for Best Director (Huston), Best Adapted Screenplay (Agee and Huston), Best Actress (Katharine Hepburn), and Best Actor (Humphrey Bogart), the last of which Bogart won (his only Oscar). In 1998 and again in 2007, it was included in the American Film Institute’s list of “100 Years…100 Movies”, and it has been selected for preservation by the Library of Congress.

The story takes place in Africa in 1914 at the start of World War I, and the film attracted much attention at the time of its release for having been shot entirely on location. Like many of director Huston’s works (e.g., THE MALTESE FALCON, KEY LARGO, MOBY DICK and the American theatrical premiere of Sartre’s NO EXIT), it focuses on the interactions of a small group of eccentric characters in a confined situation. In this case, it is only two characters — Rose, an English missionary spinster in her thirties, and Charlie Allnutt, a grizzled riverboat captain — thrown together on a small steamer boat (the eponymous African Queen) traveling downriver with the goal of blowing up a 100-ton German gunboat. The river journey motif links it with such prior literary works as THE ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN and Conrad’s HEART OF DARKNESS, and subsequent movies like Herzog’s AGUIRRE THE WRATH OF GOD and Coppola’s APOCALYPSE NOW.

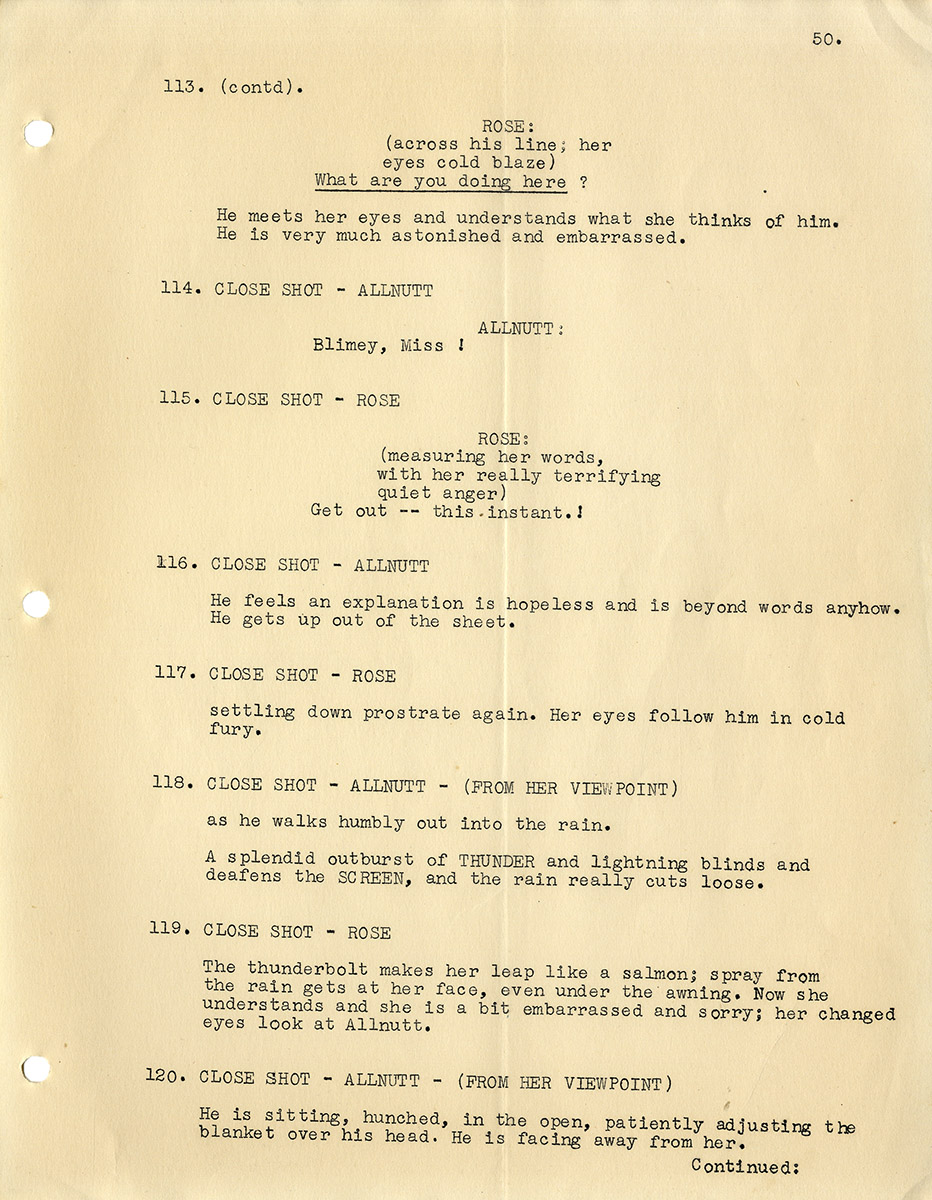

The screenplay — a shooting script very close to what was actually filmed — appears to be mostly Agee’s work, and it reflects the author’s novelistic style with scene descriptions that are detailed both visually and psychologically. For example:

Rose at dead center, Brother at he left, in profile, Allnutt at her right, opposite Brother, in profile. The room is so shaded against heat, it is gloomy. The silence, gloom, and heat are stifling. Rose is pouring the second of the three cups of tea; she pours a third. Brother is deep in the news of a Mission paper. Allnutt sits oppressed by the silence, like a child on his good behavior. A long silence, while Rose leisurely pours.

Conceived as a vehicle for two star performers, the charm of the screenplay and film emerges from the initial comedic incompatibility of prim Rose and earthy Charlie who over the course of their journey inevitably fall in love. Huston was so enamored with his characters that he changed the conclusion of the story to give them a happy ending. In the book, Charlie and Rose fail in their attempt to sink the German ship, and it is instead sunk by the British Navy as Rose and Charlie watch from the shore. In the Agee/Huston screenplay, their mission is a success.

Out of stock

Related products

-

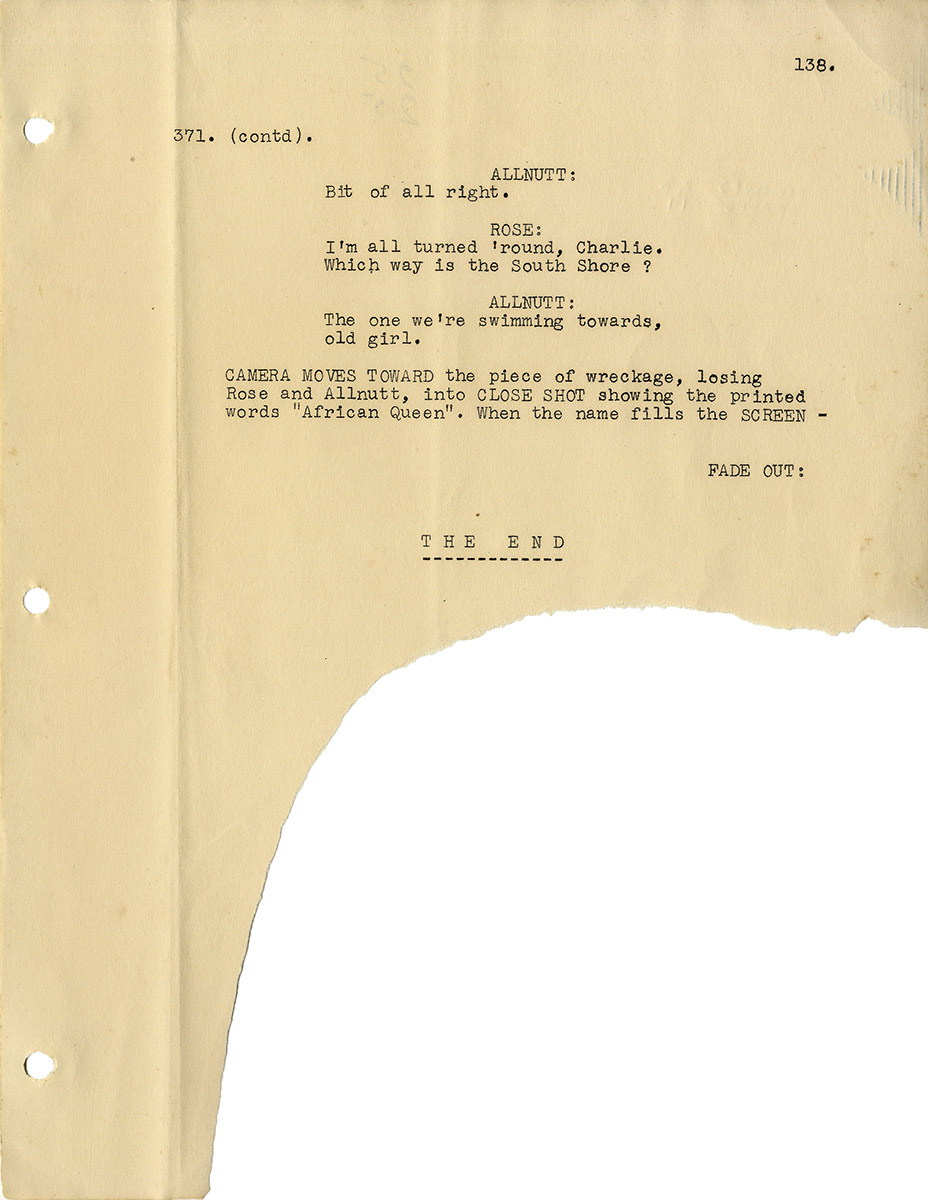

John Singleton (writer, director) HIGHER LEARNING (Jan 26, 1994) Rainbow film script

$500.00 Add to cart -

SLEEP ON THE ROOF (1967) Unproduced script based on the life of Margaret Sanger

$500.00 Add to cart -

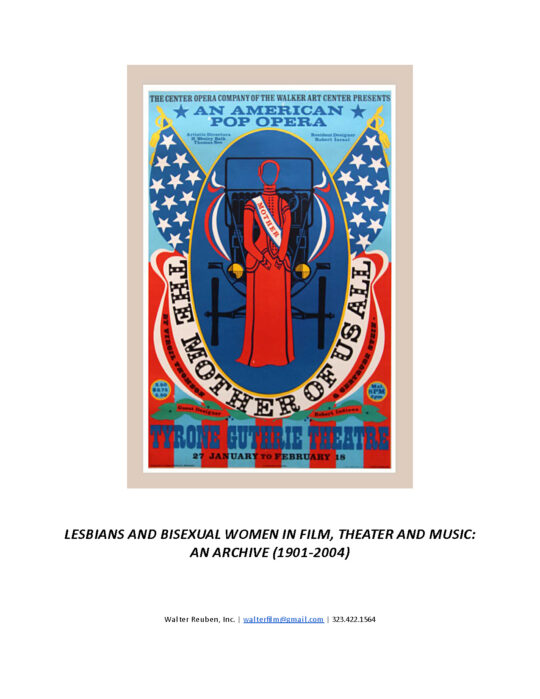

LESBIANS AND BISEXUAL WOMEN IN FILM, THEATER & MUSIC (1901-2004) Archive

$40,000.00 Add to cart -

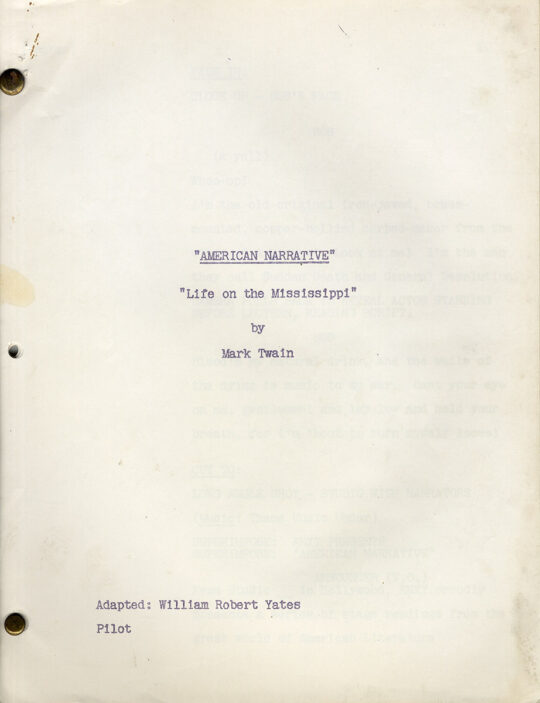

Mark Twain (source) LIFE ON THE MISSISSIPPI (ca. 1956) TV script adapted by William Robert Yates

$300.00 Add to cart