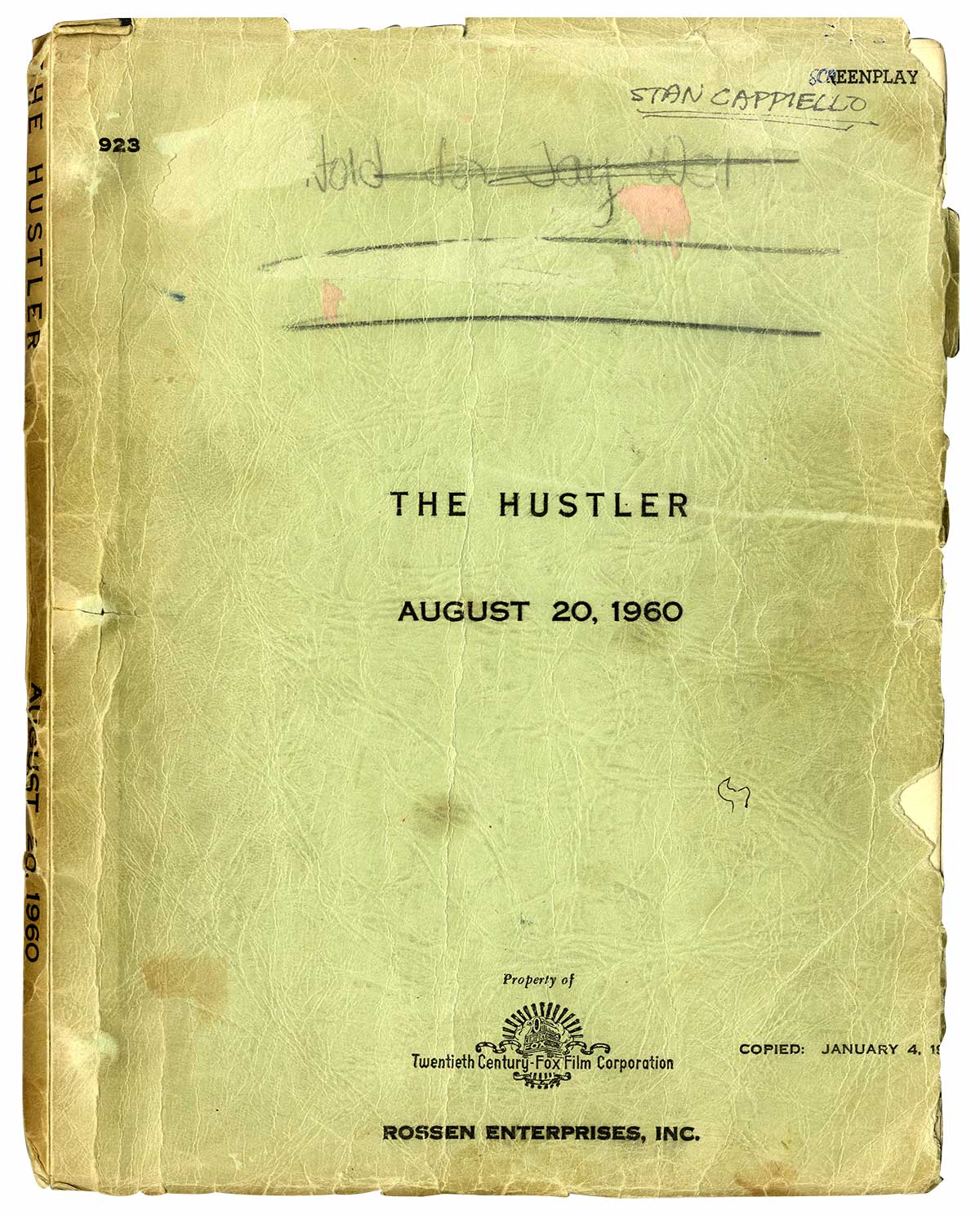

HUSTLER, THE (1960) Script

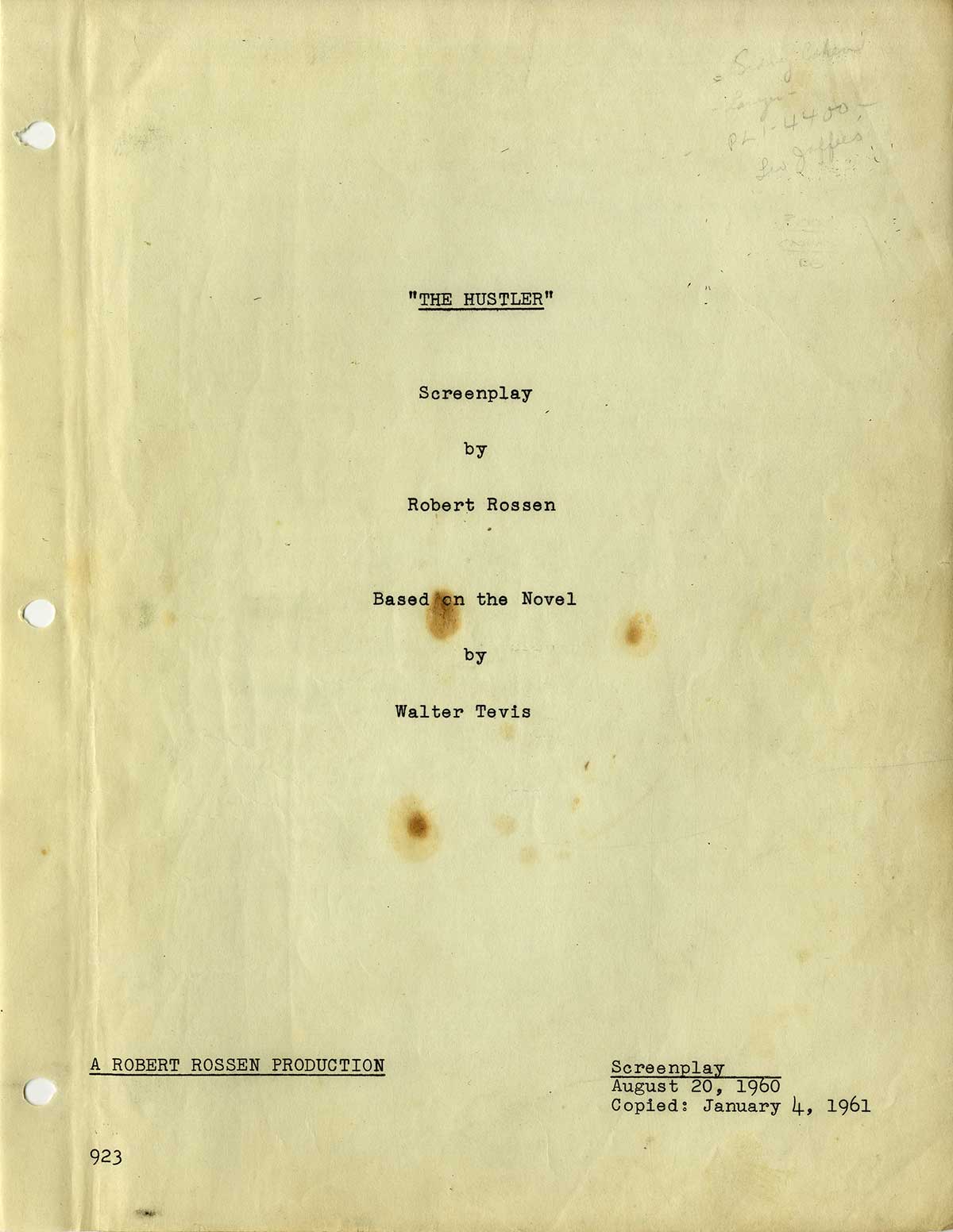

Dated August 20, 1960 Based on the Novel by Walter Tevis August 20, 1960. Robert Rossen (screenwriter, director) Hollywood: Twentieth Century Fox, 1960. Vintage film script, quarto. Printed wrappers, with some stains, wear, and chipping to yapped edges, a few spots in text, with one MS change to dialogue in an unknown hand, overall NEAR FINE in VERY GOOD- covers, 136 pp.

For writer/film director Robert Rossen (born New York City, March 16, 1908 – died February 18, 1966), THE HUSTLER represented a major comeback. After attending New York University and working as a boxer, pool hustler, and theater writer/director, among other jobs, Rossen established his reputation as a Hollywood screenwriter in the late 1930s and early 40s with films like THEY WON’T FORGET (Mervyn LeRoy, 1937), THE ROARING TWENTIES (Raoul Walsh, 1939), THE SEA WOLF (Michael Curtiz, 1941), and THE STRANGE LOVE OF MARTHA IVERS (Lewis Milestone, 1946), graduating in the late 40s to writer/director with movies like JOHNNY O’CLOCK (1947), the boxing drama BODY AND SOUL (1947), and ALL THE KING’S MEN (1949), a political noir loosely based on the career of demagogue Huey Long that was honored with Academy Awards for Best Picture (Robert Rossen Productions) and Best Actor (Broderick Crawford). Rossen was personally nominated for Best Director and for Best Adapted Screenplay (from Robert Penn Warren’s novel).

Then, at what might have been the peak of his career, Rossen was blacklisted for having been a member of the Communist Party. Effectively exiled from Hollywood throughout the 1950s, Rossen continued to direct off-beat projects like ALEXANDER THE GREAT (1956 – shot in Spain), ISLAND IN THE SUN (1957 – shot in the West Indies), and THEY CAME TO CORDURA (1959). Shot entirely on location, THE HUSTLER (1961) was a return to Rossen’s New York City pool hustling roots.

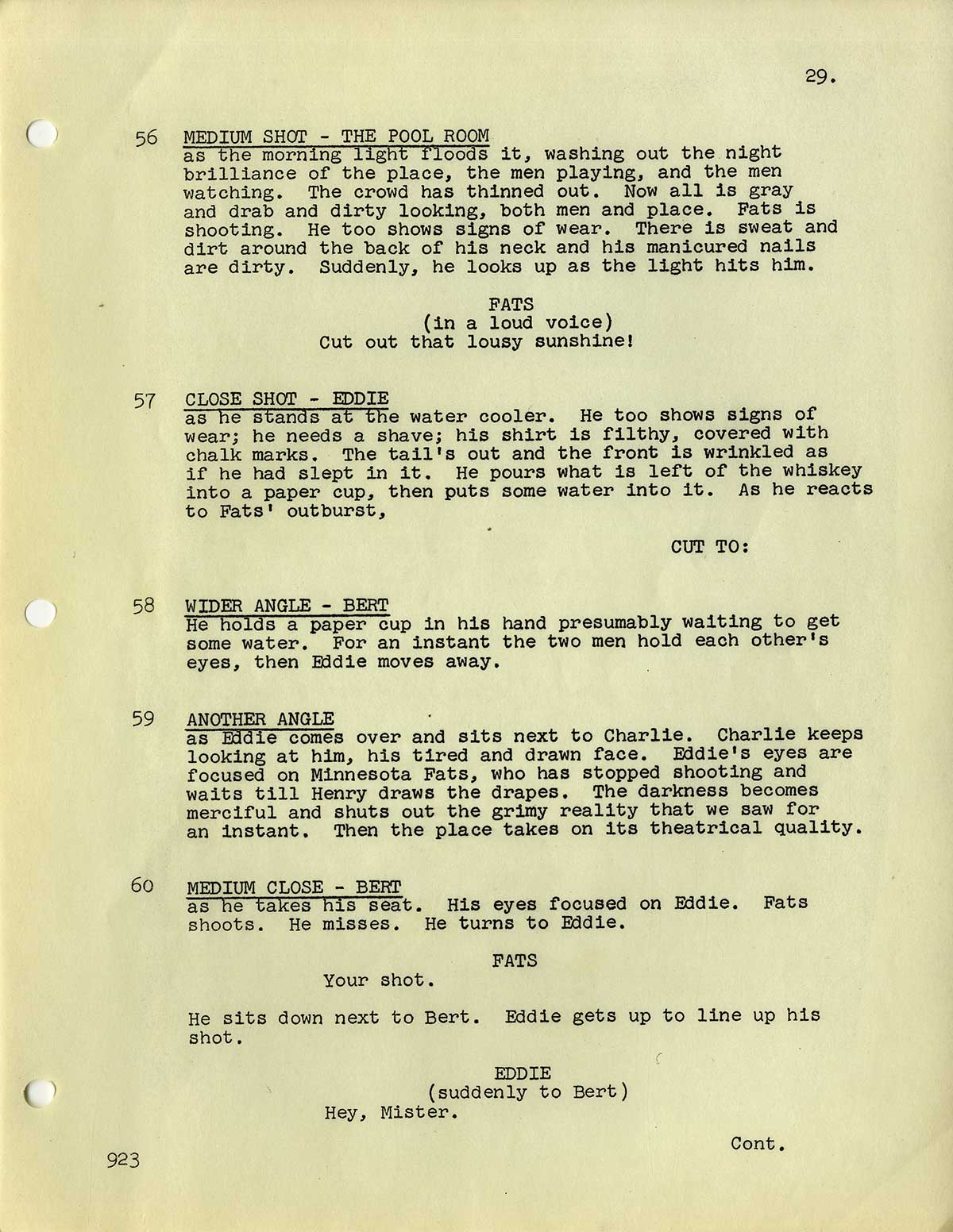

While the movie might be characterized as a sports noir (like Rossen’s BODY AND SOUL), Rossen himself described the film’s style as “neo-neo-realistic.” It’s fundamentally a story about character and character interactions with billiards as a background. Deceptively, the story at first seems to be about the battle of skills between up-and-coming pool hustler “Fast” Eddie Felson (Paul Newman) and seasoned professional pool player Minnesota Fats (Jackie Gleeson). However, after Eddie loses his first big confrontation with Fats, the focus shifts to Eddie’s relationships with an emotionally fragile woman named Sarah (Piper Laurie) and a professional gambler/would-be manager named Bert (George C. Scott) who, in his ruthless need to diminish and control everyone around him, becomes the narrative’s true antagonist.

In terms of autobiography, the ultimate betrayal of Sarah by Eddie – for the sake of “winning” – has been said to parallel the Faustian bargain made by Rossen when he elected to name names to the House Un-American Activities Committee. Though all of Rossen’s work reflects an interest in social themes – particularly the meaning of success in a capitalist system – his later films like THE HUSTLER and his last film, LILITH (1964), focus increasingly on perverse and dysfunctional relationships. In Rossen’s films we see a world of damaged men and damaged women, of predators and prey.

In Rossen’s HUSTLER screenplay the difference between winning and losing is the difference between talent and character:

BERT

I don’t think there’s a pool player alive who shoots better pool than I saw you shoot the other night.

(pushes a potato chip into his mouth)

You got talent.

EDDIE

So I got talent? Then what beat me?

BERT

Character.

EDDIE

(laughing)

Sure, sure.

BERT

You’re damn right I’m sure. Everybody’s got talent. I got talent. You think you can play big-money, straight pool – or poker – for forty straight hours on nothing but talent?

(leans toward Eddie)

You think they call Minnesota Fats the best in the country just because he’s got talent?

(sips his drink)

Minnesota Fats has more character in one finger than you got in your whole skinny body.

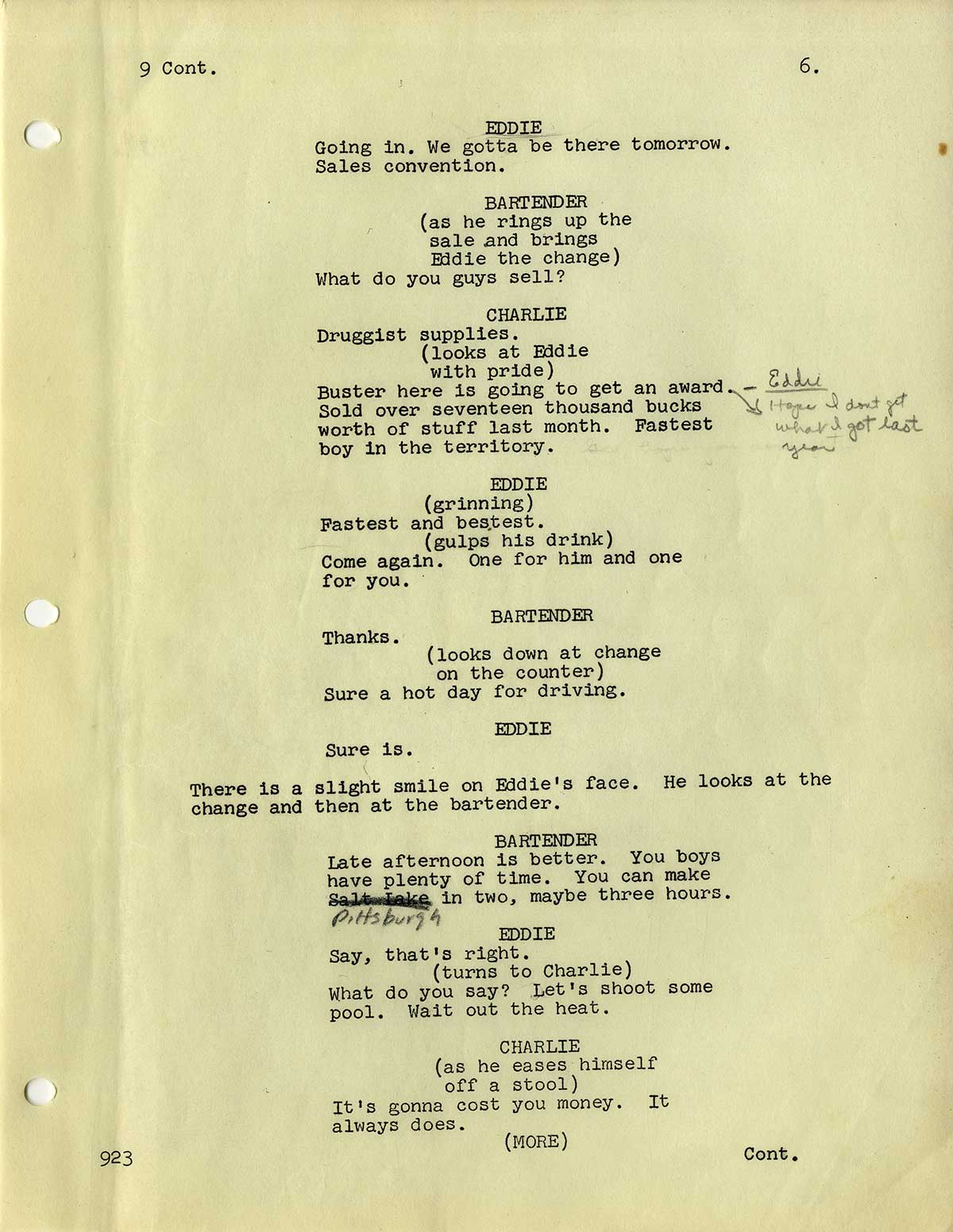

The differences between Rossen’s screenplay and the completed movie are largely a matter of trimming. The screenplay’s opening scene, establishing the story’s principal location, the Ames Pool Hall (called “Bennington’s” in the screenplay, reminiscent in many ways of Harry Hope’s saloon in O’Neill’s THE ICEMAN COMETH), has been deleted, and some lines have been deleted or trimmed in almost every scene. Much of what is expressly stated in the deleted dialogue is implied in the completed film through an attitude or a glance. Among other modifications, a scene between Eddie, Bert, and Sarah that takes place in a car in the screenplay takes place in a railway car in the movie.

THE HUSTLER is in every way a triumph, a screenplay that synthesizes the best of American theatrical realism – the plays of Eugene O’Neill, Arthur Miller, and Clifford Odets – with the best of the social realist tradition in American film.

Out of stock

Related products

-

![(Blaxploitation film) BLACK BELT JONES [1974] Film script by Oscar Williams](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/BlackBeltJonesSCR_a-540x693.jpg)

(Blaxploitation film) BLACK BELT JONES [1974] Film script by Oscar Williams

$750.00 Add to cart -

![CHINATOWN [ca. 1973] Jack Nicholson's copy of early draft film script by Robert Towne](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/ChinatownSCR_a-540x693.jpg)

CHINATOWN [ca. 1973] Jack Nicholson’s copy of early draft film script by Robert Towne

$18,500.00 Add to cart -

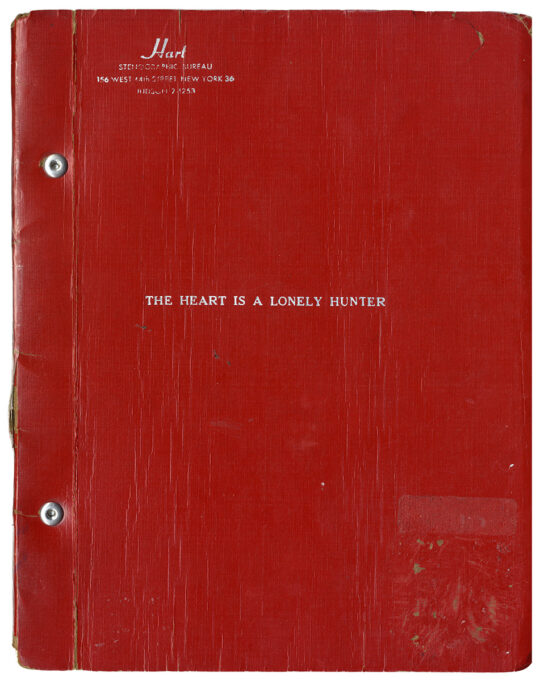

Carson McCullers (source) THE HEART IS A LONELY HUNTER (Aug 26, 1963) Film script by Thomas C. Ryan

$1,000.00 Add to cart -

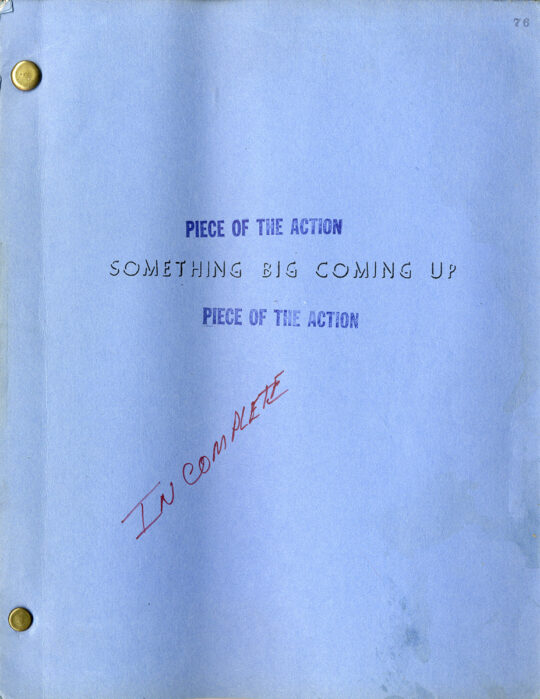

(African American film) A PIECE OF THE ACTION [working title: SOMETHING BIG COMING UP] (Nov 1, 1976) Film script

$750.00 Add to cart