James Joyce (source) PASSAGES FROM JAMES JOYCE’S FINNEGANS WAKE (1963) Final Shooting script

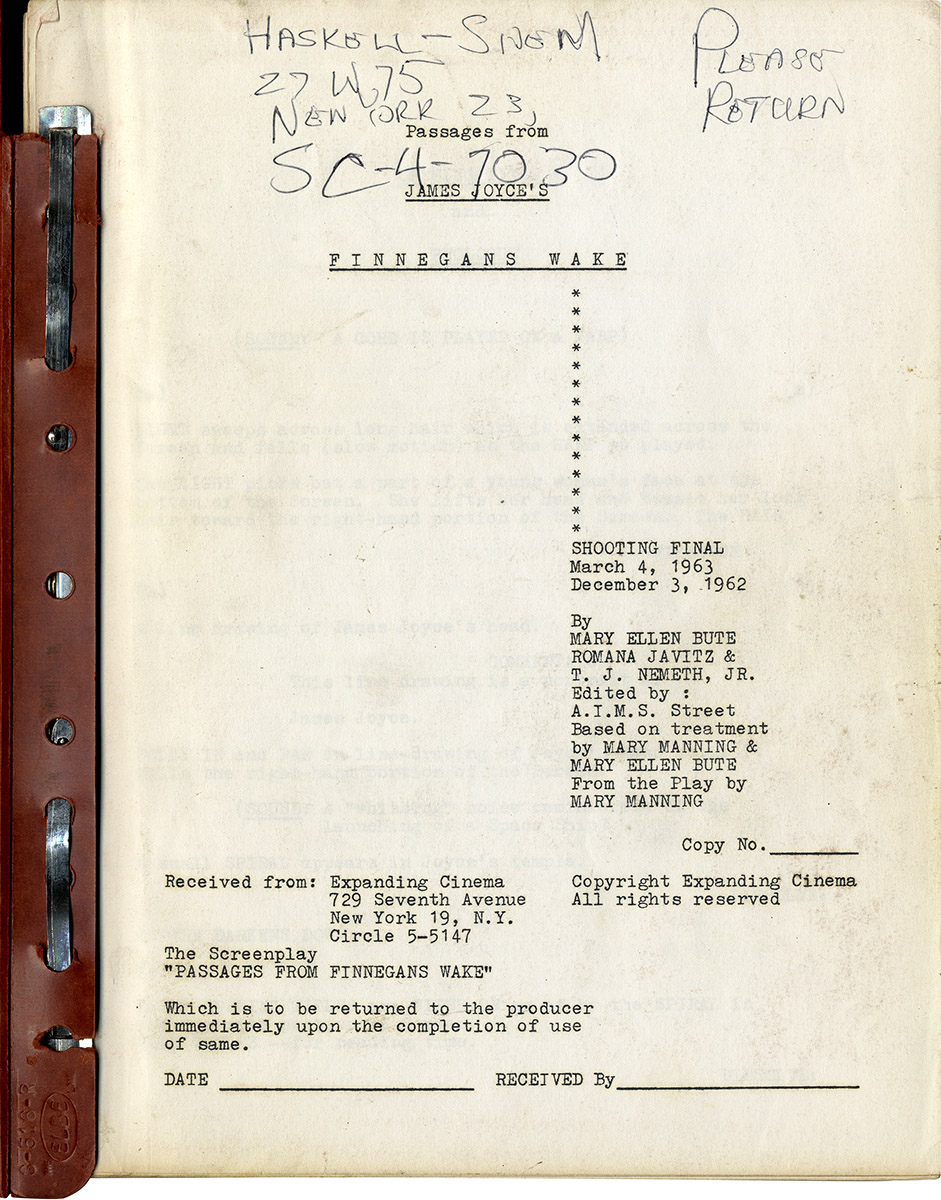

New York: Expanding Cinema, [1963]. Vintage original film script, 11 x 8.5″ (28 x 22 cm.) Brown untitled wrappers. Title page present, dated March 4, 1963 and December 3, 1962, noted as Shooting Final, with credits for screenwriters Mary Ellen Bute, Romana Javitz, and T. J. Nemeth Jr and editor A.I.M.S. Street. 148 leaves, with last page of text numbered 139. Mimeograph duplication, with onionskin revision pages throughout. Some pages detaching and wrapper slightly cracked. Bound internally with prong binding. This script belonged to actor Peter Haskell, with his holograph annotations throughout and his shooting schedule laid in. Some pages are folded inward, others are laid in loosely. Pages very good+, wrapper very good+.

Mary Ellen Bute’s final film, and one of the only cinematic adaptations of James Joyce’s masterfully complex work of fiction, Finnegans Wake. Shot over a two year period, Bute was tasked with transforming Joyce’s impenetrable prose without losing any of the work’s surreal, lyrical essence. The subsequent film maintains the original novel’s oneiric style. Bute and her husband, Ted Nemeth, were longtime collaborators, and Nemeth worked as both cinematographer and producer of the film. In 1965, it was honored at the Cannes Film Festival as Best Debut and remains Bute’s sole feature length film.

Mary Ellen Bute (1906-1983) was born in Houston, Texas, and spent most of her creative life in New York City. She was one of America’s first important woman filmmakers, a pioneer in the field of experimental animation who specialized in setting abstract images to music. One of her earliest short films, RHYTHM IN LIGHT (1934), shot in black and white, combines abstract moving forms with the music of Edvard Grieg. Her first color short, SYNCHROMY NO. 4: ESCAPE (1937), was set to the music of J.S. Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, and almost certainly inspired the very similar Toccata and Fugue episode of Walt Disney’s 1941 FANTASIA. Though her films were unapologetically avant-garde, they were screened as short subjects in movie theaters across the country and viewed by millions.

In the mid-1950s, Bute transitioned from animation to live-action filmmaking. Her 1958 short film, THE BOY WHO SAW THROUGH, was a comparatively conventional narrative starring a 15-year-old Christopher Walken. In the 1960s and 1970s Bute worked on two films that were never completed: an adaptation of Thornton Wilder’s 1942 play THE SKIN OF OUR TEETH, and a movie about Walt Whitman to be titled OUT OF THE CRADLE ENDLESSLY ROCKING.

Bute’s last completed film, the feature-length PASSAGES FROM JAMES JOYCE’S FINNEGANS WAKE (1966) was her magnum opus, based on a modernist novel that most people would have considered unfilmable. Relying in part on a theatrical adaptation of Joyce’s “word salad” novel by Mary Manning, Bute’s movie is a surrealistic dream narrative, not darkly surreal like Buñuel and Dalí’s UN CHIEN ANDALOU (1929), but playfully surreal like René Clair’s experimental short, ENTR’ACTE (1924), and like Bute’s predecessors in the international avant-garde, employing every cinematic trick in the book. The movie was screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 1965 and awarded Best Debut of the Year.

The “Shooting Final” screenplay by Mary Ellen Bute, et al. does a masterful job of finding and clarifying the essential narrative arc of Joyce’s novel. Briefly summarized, the movie tells the story of a pub keeper in Dublin who has a dream vision of his own death — and his subsequent resurrection or awakening from that death. To quote from the film’s introduction, “Finnegan — otherwise known as H.C. Earwicker, or Here Comes Everybody — has two sons, Shem and Shaun who are also conflicting parts of himself which invade him; and his daughter Iseult, who is a younger manifestation of his wife Anna Livia Plurabelle (ALP), who is also his soul and the River Liffey.” Joyce believed that when we are asleep and dreaming, we come into contact with archetypes universal to mankind throughout its entire history.

Bute’s movie consists of evocative imagery, episodes, montages, and vaudeville-like skits, many of them taking place at Finnegan’s Irish wake. The images are Bute’s, but every word of dialogue or narration in the film comes from Joyce. As numerous commentators have pointed out, the puns and double meanings of Joyce’s language are easier to understand when heard out loud (particularly when spoken by Bute’s cast of Irish thespians). To further help viewers understand Joyce’s singular language, the film is subtitled throughout. Unsurprisingly, in light of Bute’s earlier work, PASSAGES FROM JAMES JOYCE’S FINNEGANS WAKE is a very musical film, aurally and visually.

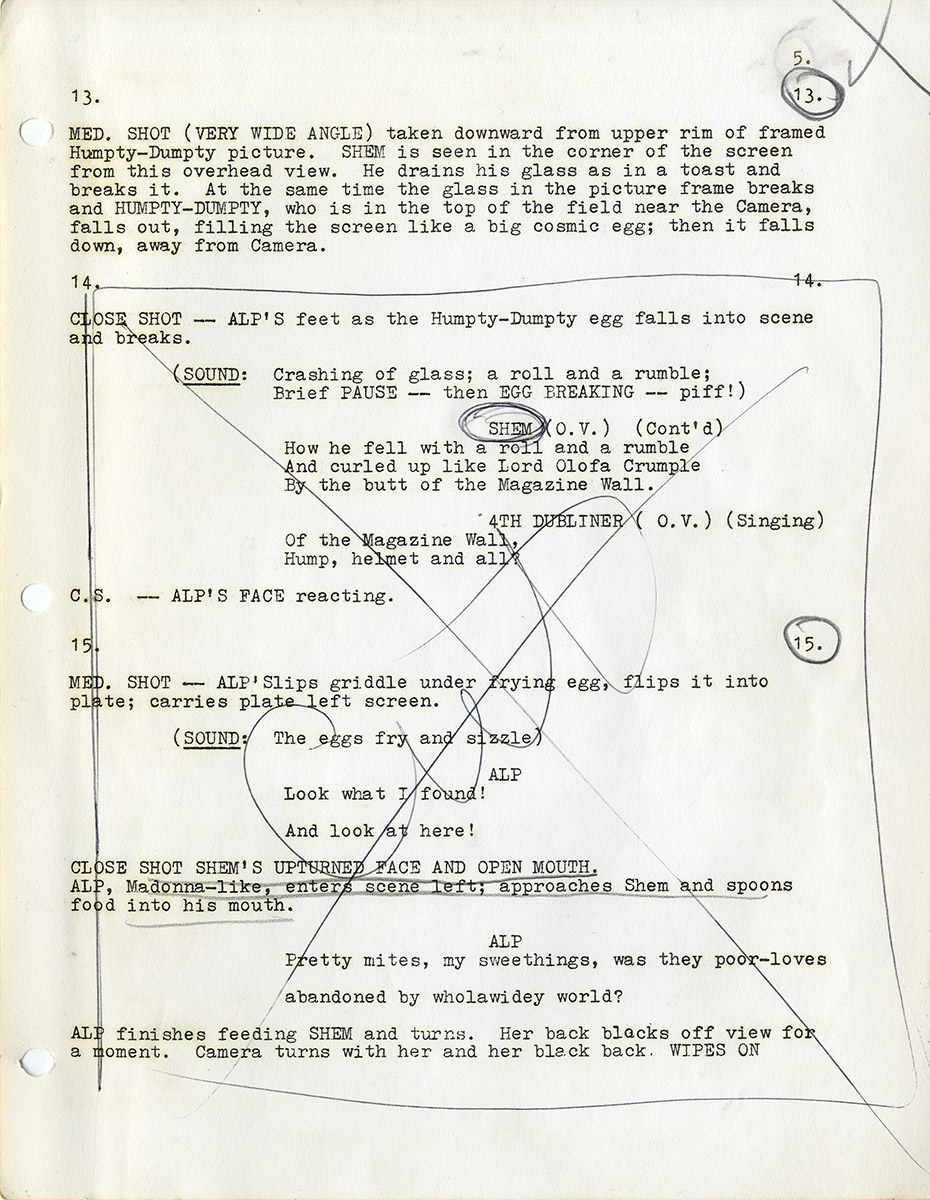

Bute’s adaptation of FINNEGANS WAKE is nothing if not ambitious. In attempting to make a film saturated with Joyce’s protean language, the challenge to the screenwriter is to provide a flow of imagery that complements the language. Here’s one example of how Bute and her collaborators met that challenge:

MED. SHOT OF ALP ABOVE FINNEGAN’S HEAD IN THE COFFIN

She is holding a lighted candle in one hand. The FOCUS on the candle

flame makes it look like a star. ALP puts her free hand in front of the

candle flame to protect it from a breeze, which causes the flame to flicker

and disturb the shawl over her head. The candle flame makes the edge of

her hand translucent and reflects the light down on Finnegan’s face, and

up on hers.

Critics praised the movie. Dwight MacDonald of Esquire wrote that it, “Brings out the meaning and beauty and the comedy with clarity surpassed only by Joyce himself.” Dilys Powell of the London Times called it, “Extraordinary. It is played with delight by an Irish cast and its elusive narrative of nightmare, intimations of human history and hopeful reawakening — half-understood words and mysterious images echoing one another — has sent me scurrying back to Joyce.” While Stanley Kauffmann of New American Review wrote, “It achieves the innermost effect of the great dream novel.” Along with Joseph Strick’s ULYSSES and John Huston’s THE DEAD, Mary Ellen Bute’s PASSAGES FROM JAMES JOYCE’S FINNEGANS WAKE remains one of the few successful attempts to bring Joyce’s writings to the movie screen.

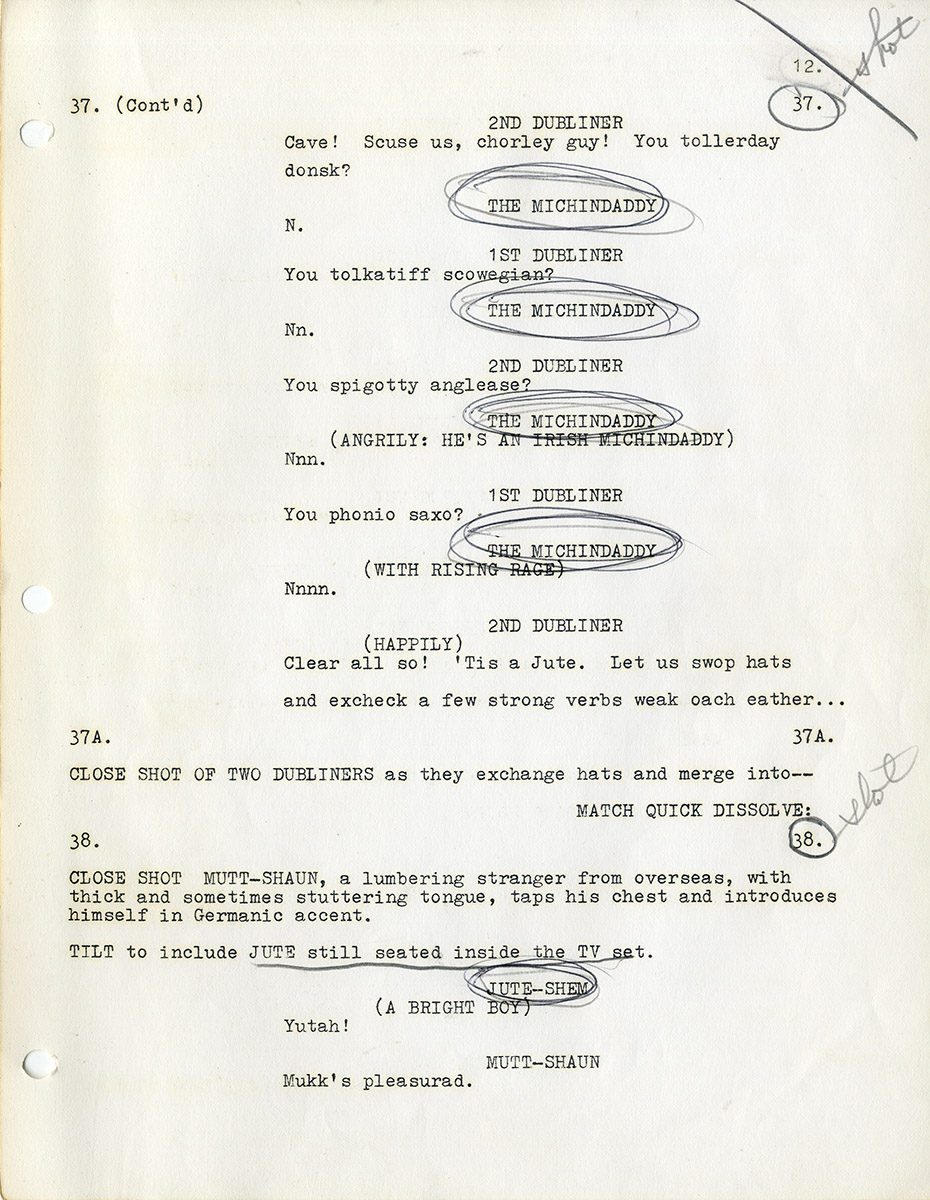

[NOTE: This copy of the screenplay very likely belonged to the actor who played Shem, as Shem’s name is circled in pencil wherever it appears, and his scene numbers are circled with the word “Shot” written next to them, presumably to indicate they have been filmed. Also written in pencil are stage directions for Shem, e.g., “Shem seated” and some added lines of dialogue.]

Out of stock

Related products

-

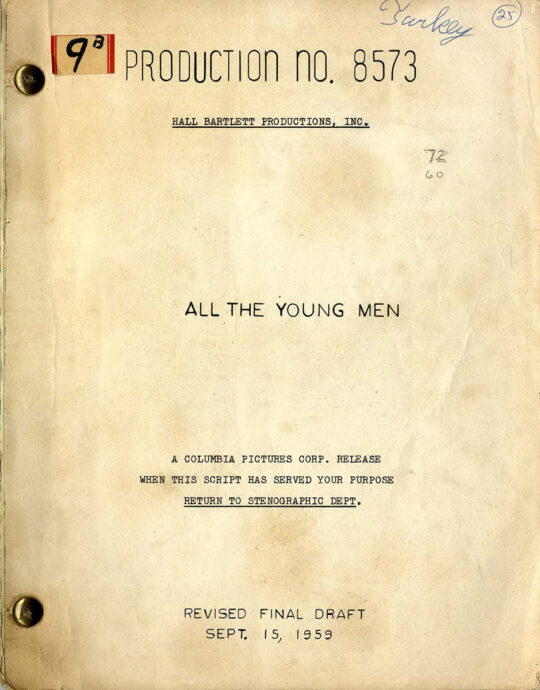

ALL THE YOUNG MEN (Sep 15, 1959) Revised Final Draft script by Hall Bartlett

$450.00 Add to cart -

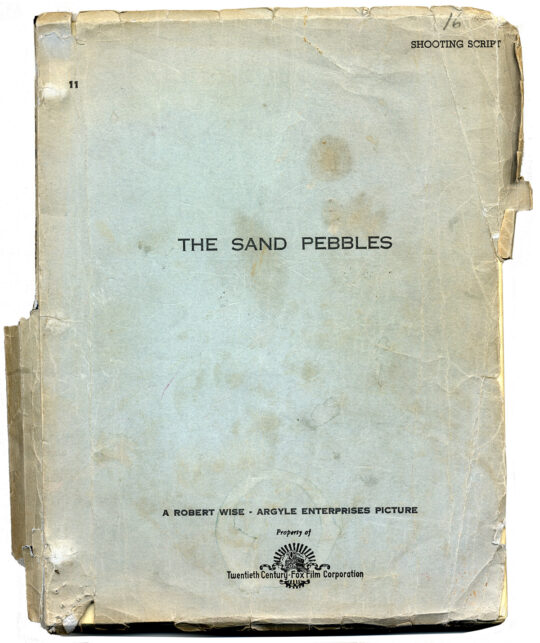

SAND PEBBLES, THE (Nov 1, 1965) Shooting script by Robert Anderson

$1,150.00 Add to cart -

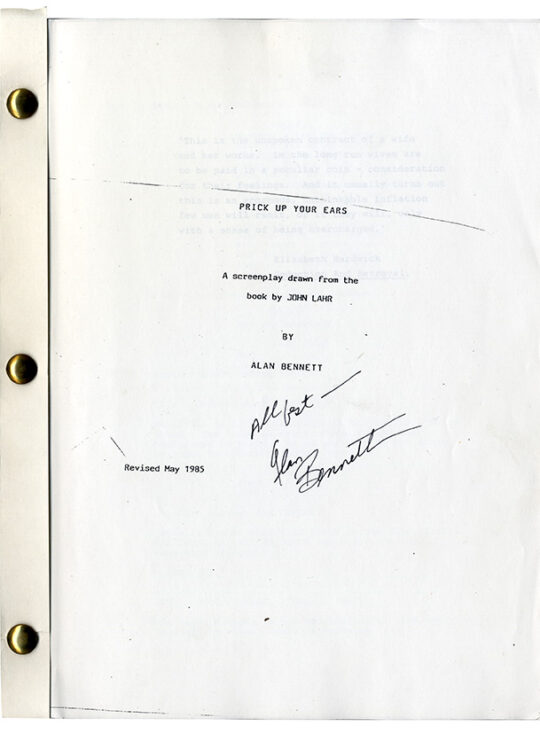

PRICK UP YOUR EARS (May 1985) Revised film script

$650.00 Add to cart -

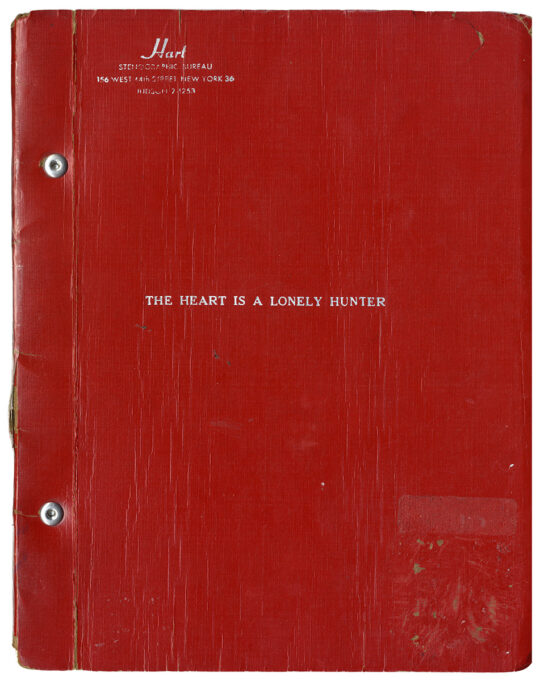

Carson McCullers (source) THE HEART IS A LONELY HUNTER (Aug 26, 1963) Film script by Thomas C. Ryan

$1,000.00 Add to cart