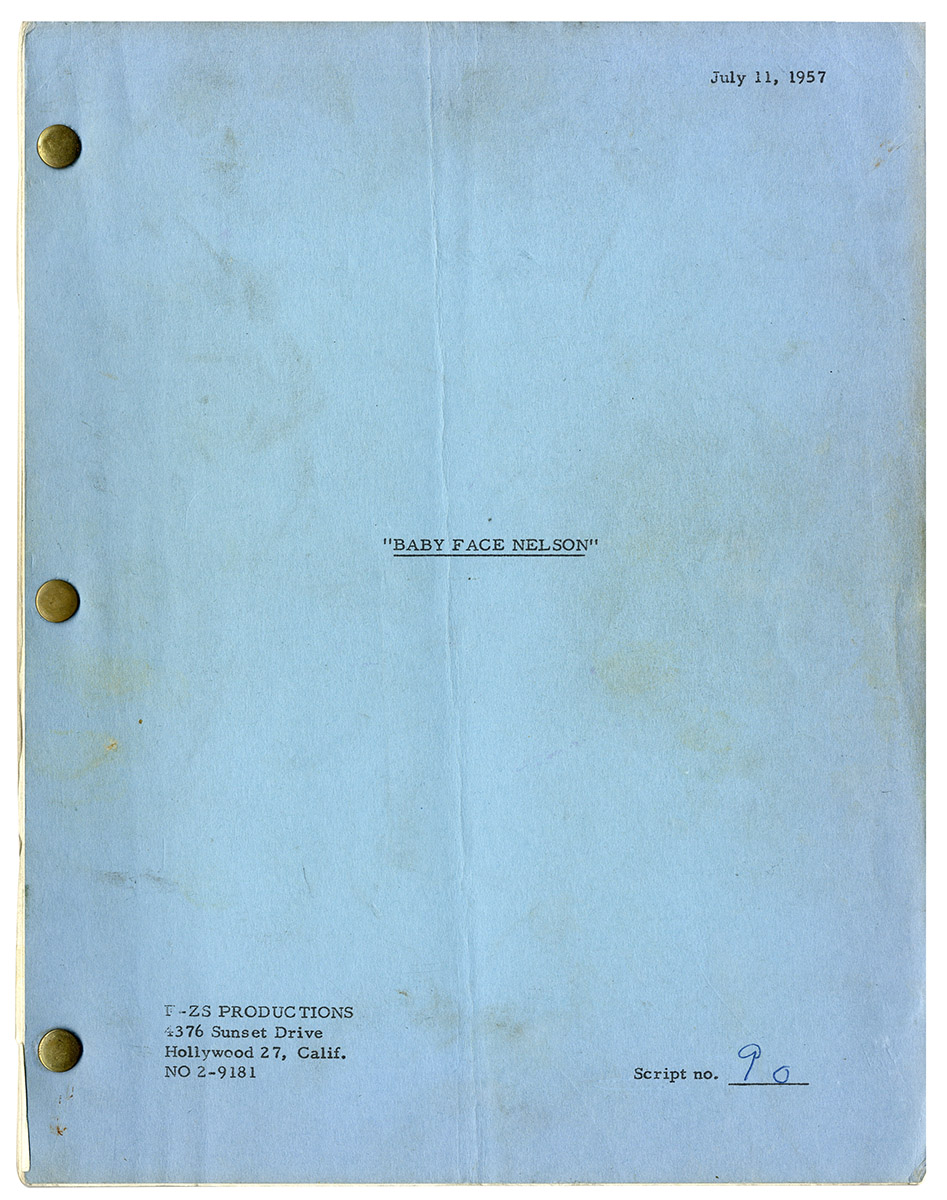

BABY FACE NELSON (Jul 11, 1957) Film script by Irving Shulman

Hollywood: F-ZS Productions, 1957. Vintage original film script, 11 x 8.5″ (28 x 22 cm.) dated July 11, 1957 (with one blue page dated 7/15/57). Printed wrappers, mimeograph, brad bound, 109 pp., just about fine.

By the time Don Siegel directed BABY FACE NELSON in 1957, he had already made half a dozen crime films, including the classic RIOT IN CELL BLOCK 11 (1954). In 1956, he directed what many consider to be his masterpiece, THE INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS, a science fiction thriller. Still ahead were more classics like THE LINEUP (1958), THE KILLERS (1964), and DIRTY HARRY (1971). He was an acknowledged master of the genre movie.

The chief screenwriter of BABY FACE NELSON (sharing on-screen credit with Daniel Mainwaring) was Irving Shulman, best known for writing the novels The Amboy Dukes, Cry Tough and Platinum High School, as well as a best-selling intimate biography of Jean Harlow, all of which were adapted into movies.

Shulman’s economical and effective BABY FACE NELSON screenplay was adapted from his own unpublished novel. It closely follows the real-life story of gangster Lester Gillis aka George Nelson aka “Baby Face” Nelson, an associate of notorious 1930s gangster John Dillinger, who was dangerous enough in his own right to be briefly labeled “Public Enemy No. 1” by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. The principal female character, Sue, played in the movie by Carolyn Jones, is loosely based on Nelson’s real-life wife, Helen.

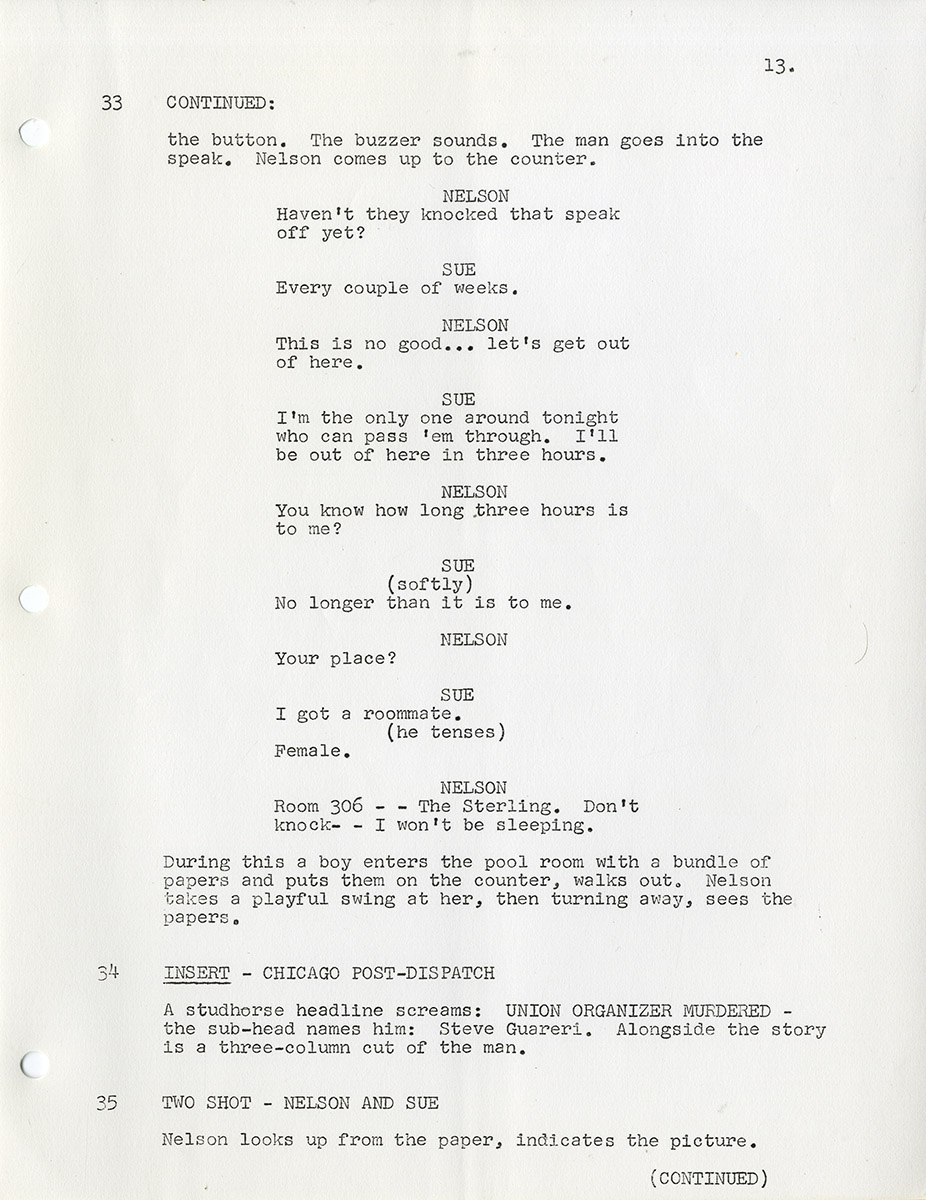

This screenplay draft was clearly tailored to the talents and persona of Mickey Rooney who plays the title role. The fact that Rooney was already attached to the project at the time this draft was written is confirmed by the interior title page which reads, “Mickey Rooney as Baby Face Nelson.” In contrast to many of the Westerns and crime thrillers of the 1940s and 1950s, Shulman’s screenplay provides no sociological or psychological explanation for the characters’ behavior. Nelson is a murdering psychopath simply because that is who he is. His girlfriend Sue loves him unconditionally because that is what she does. In that sense, the screenplay feels very modern, looking forward to the existential crime thrillers of directors like Jean-Pierre Melville and Walter Hill who define their characters solely by their actions.

Shulman’s screenplay is unusually violent for the time when it was made. While the movie follows this screenplay draft quite closely — it was apparently the shooting script — at least two of the more gruesome murders described in the script are not shown on-screen in the completed film, leading one to believe they were shot, but removed later for censorship reasons. (In 1957, the Production Code was still in force.)

Another one of the screenplay’s virtues is that it provides a plethora of juicy roles for some of Hollywood’s finest veteran character actors, including Leo Gordon (Dillinger), Cedric Hardwicke (a seedy doctor), Ted de Corsia, Jack Elam, John Hoyt, Dabbs Greer, and Elisha Cook, Jr.

The screenplay’s narrative arc is a classically Shakespearean rise-and-fall story. Small-time crook Nelson is released from prison and immediately establishes his reputation by killing another hood. He reaches the big-time when he joins forces with bank robber John Dillinger and, after Dillinger is gunned down outside a movie theater, becomes Public Enemy No. 1. He grows increasingly ruthless and unsympathetic. He is pursued relentlessly by the FBI, whose agents he has murdered, and when he is finally cornered by them in a country cemetery, persuades his girlfriend to shoot him so he won’t be taken alive — ending the story on a grim but romantic note.

At which point, per Shulman’s screenplay, the camera pans upward from Nelson’s body to an inscription on a tombstone that reads:

WHEN GOOD MEN DIE, THEIR GOODNESS DOES NOT PERISH. AS FOR THE

BAD, ALL THAT WAS THEIRS DIES AND IS BURIED WITH THEM.

Regardless, contrary to the epitaph above, the legend of “bad” Baby Face Nelson lives on, immortalized in film after film, including as portrayed by Richard Dreyfuss in John Milius’s DILLINGER (1973), as a henchman to Johnny Depp’s Dillinger in Michael Mann’s PUBLIC ENEMIES (2009), and, best of all, as a hilariously manic example of bipolar disorder in the Coen Brothers’ O BROTHER WHERE ART THOU? (2000).

Out of stock

Related products

-

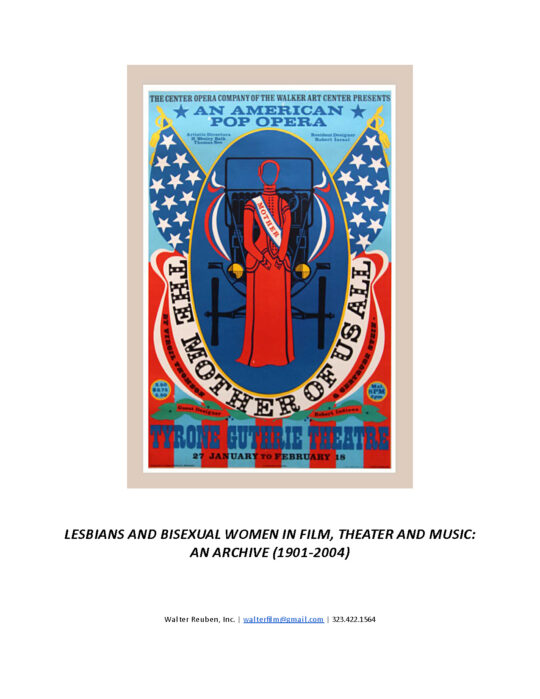

LESBIANS AND BISEXUAL WOMEN IN FILM, THEATER & MUSIC (1901-2004) Archive

$40,000.00 Add to cart -

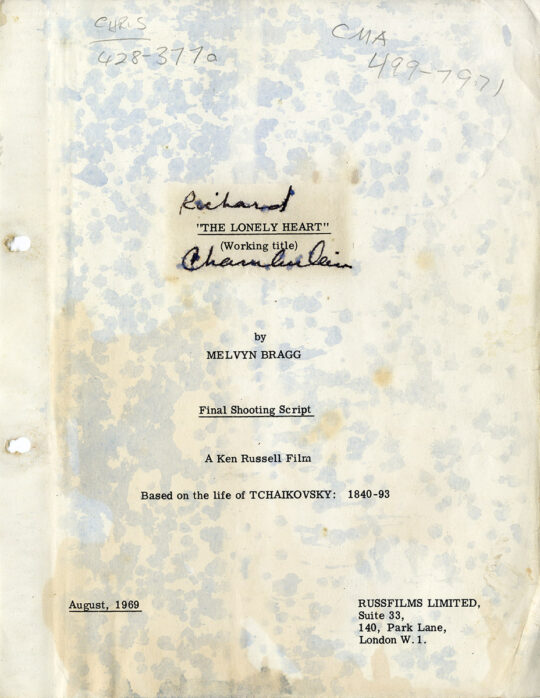

Ken Russell (director) THE MUSIC LOVERS [working title: THE LONELY HEART] (1969) Final shooting script

$3,000.00 Add to cart -

RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT, A (1987) Larry Cohen-signed script

$625.00 Add to cart -

DRESS GRAY (Mar 6, 1981) Second revision script by Gore Vidal

$500.00 Add to cart