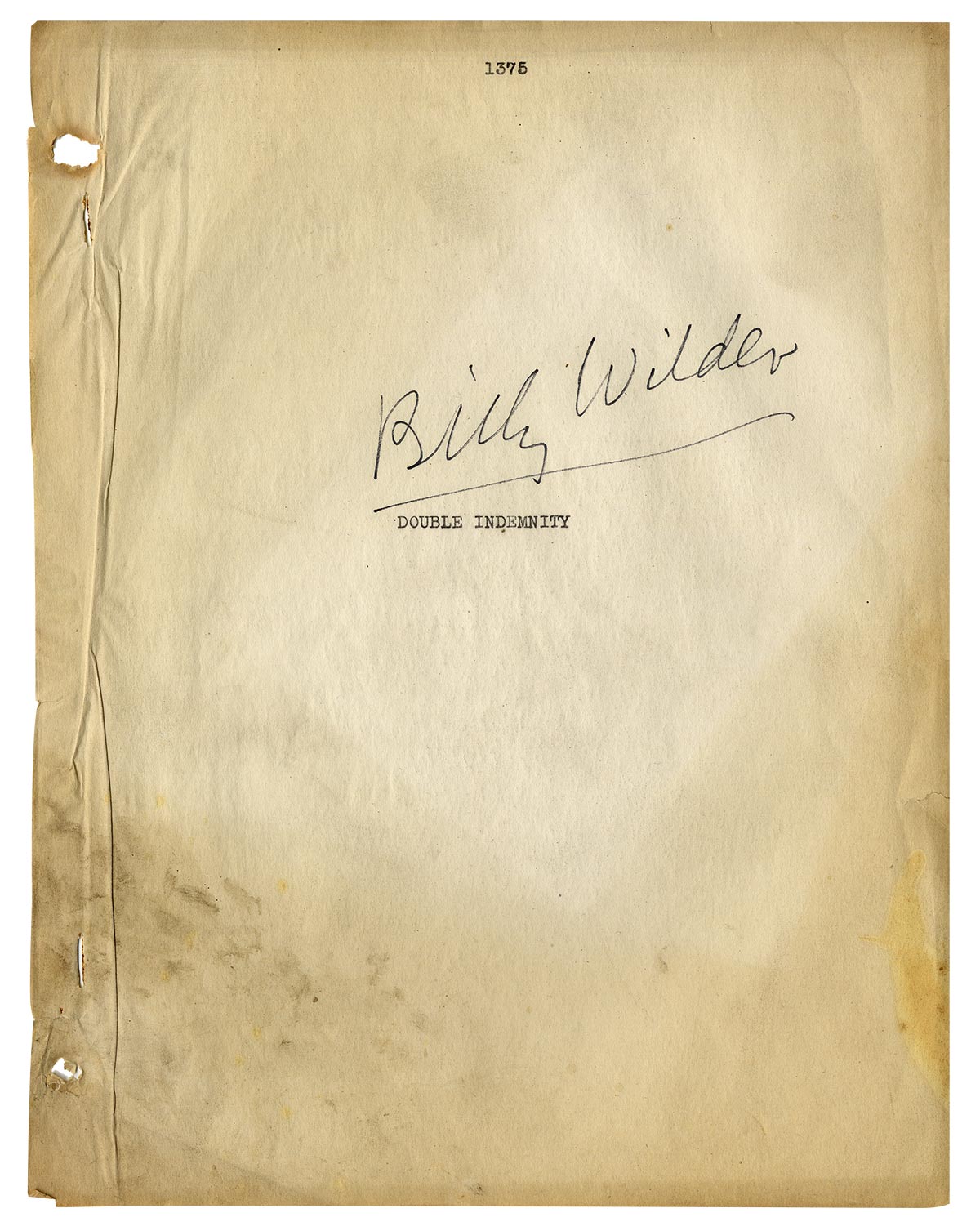

DOUBLE INDEMNITY (1944) Script signed by Billy Wilder

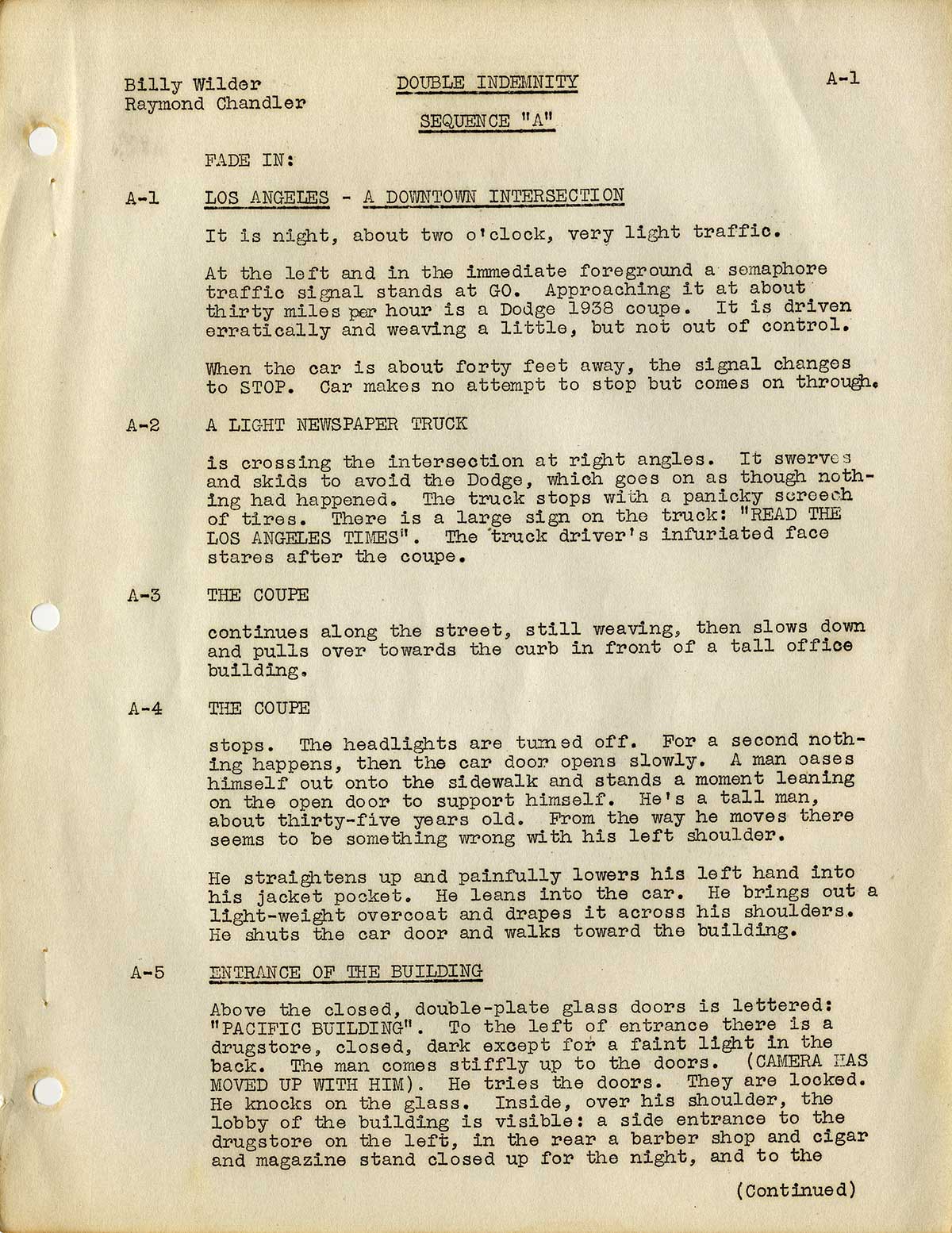

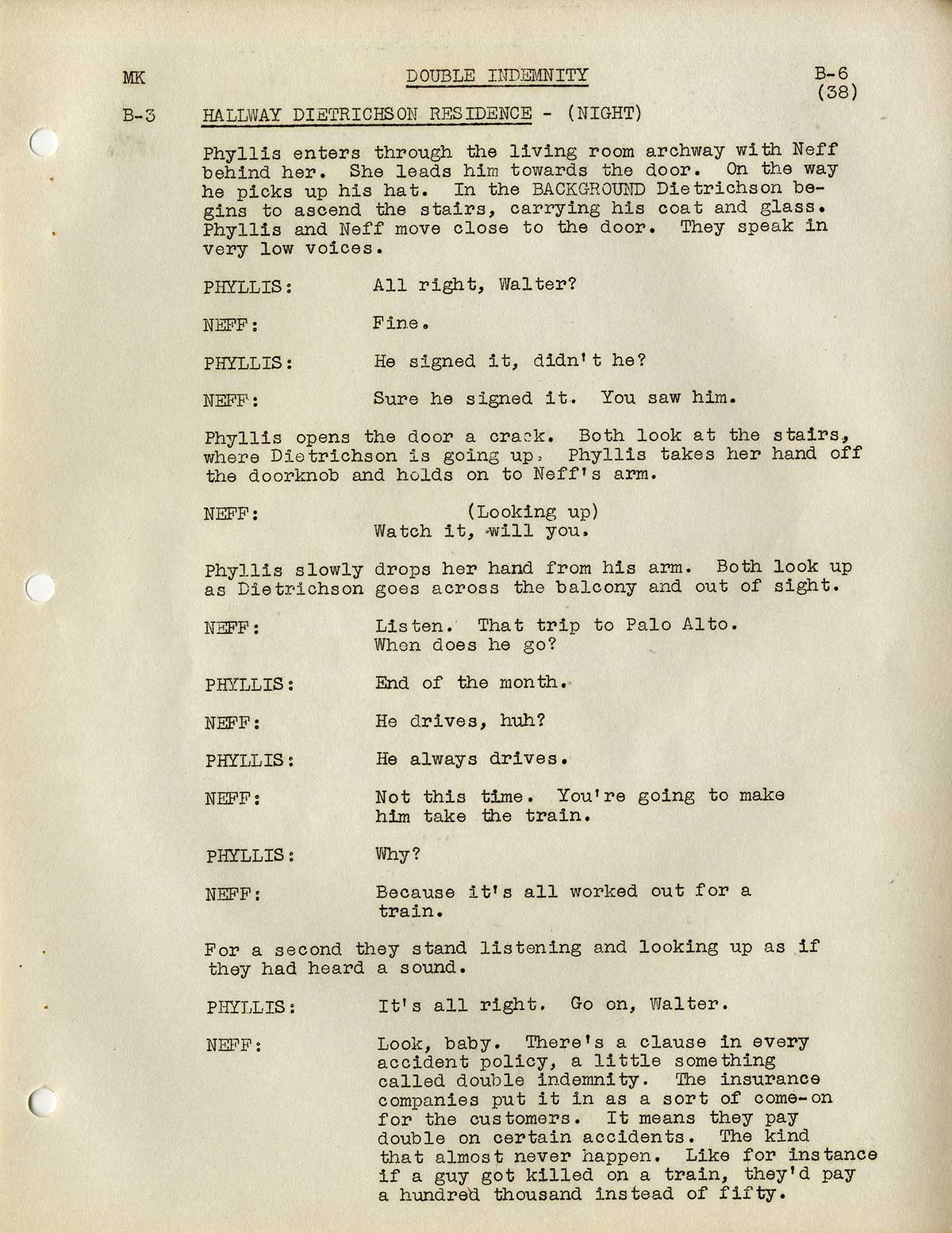

Raymond Chandler (screenwriter), Billy Wilder (co-screenwriter, director) [Hollywood: Paramount Pictures, 1944]. Quarto, self-wrappers, brad bound, mimeograph, stains to title page, otherwise just about fine, in a quarter morocco clamshell box. Signed by Billy Wilder on title page. 117 pp., with two blank leaves in all; [2], A1-A32, B1-B35, C1-C15, D1-D31, E1-E3. Title page is undated. Each of the five sequences of which the script is composed acknowledge Wilder and Chandler as writers on the first page of each sequence, except for the brief three page sequence at the end, which is the ultimately unused sequence of Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) in the gas chamber. The two preliminary leaves are the title page, followed by a cast list.

The screenplay of DOUBLE INDEMNITY melds the talents of two of America’s leading practitioners of literary noir, James M. Cain (1892-1977), who wrote the novella on which it was based, and Raymond Chandler (1888-1959), who adapted it to the screen in collaboration with Austrian-born writer/director Billy Wilder (1906-2002). As filmed by Wilder, DOUBLE INDEMNITY became the definitive American film noir – specifically, Los Angeles noir.

NEFF

I killed him for money – and a woman – and I didn’t get the money and I didn’t get the woman. Pretty isn’t it?

Cain’s novella, Double Indemnity, appeared originally as an 8-part serial in Liberty magazine in 1936. It was a follow-up to Cain’s highly successful first novel, The Postman Always Rings Twice, published in 1934, and reworks some of the same plot elements – a femme fatale, an inconvenient older husband, and the sucker she persuades to murder him. Although both of these properties immediately attracted the attention of Hollywood producers, neither of them made it onto American screens until the mid-1940s – DOUBLE INDEMNITY in 1944, THE POSTMAN ALWAYS RINGS TWICE in 1946 – after the Hollywood Production Code had loosened enough to accommodate the stories’ more sordid aspects relating to adultery and sexually motivated homicide.

As Richard Schickel points out in his useful monograph (“Double Indemnity”, BFI Publishing, 1992), one of the most important things that Chandler brought to the project – and which incidentally helped to get it past the Hollywood censors – was a strong moral center. Cain’s work has no such moral center, generally depicting a fallen world filled with sordid fallen people. Raymond Chandler’s novels, such as The Big Sleep and Farewell My Lovely, depict a similarly corrupt world, but that world is seen through the eyes of a character, detective Philip Marlowe, who is not himself corrupt. As Chandler wrote of his character, “Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. . . . He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor.” Chandler and Wilder’s screen adaptation of Cain’s novella establishes its own strong moral center in the character of Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson), the insurance investigator who is also the mentor of its insurance salesman protagonist, Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray), and his closest friend.

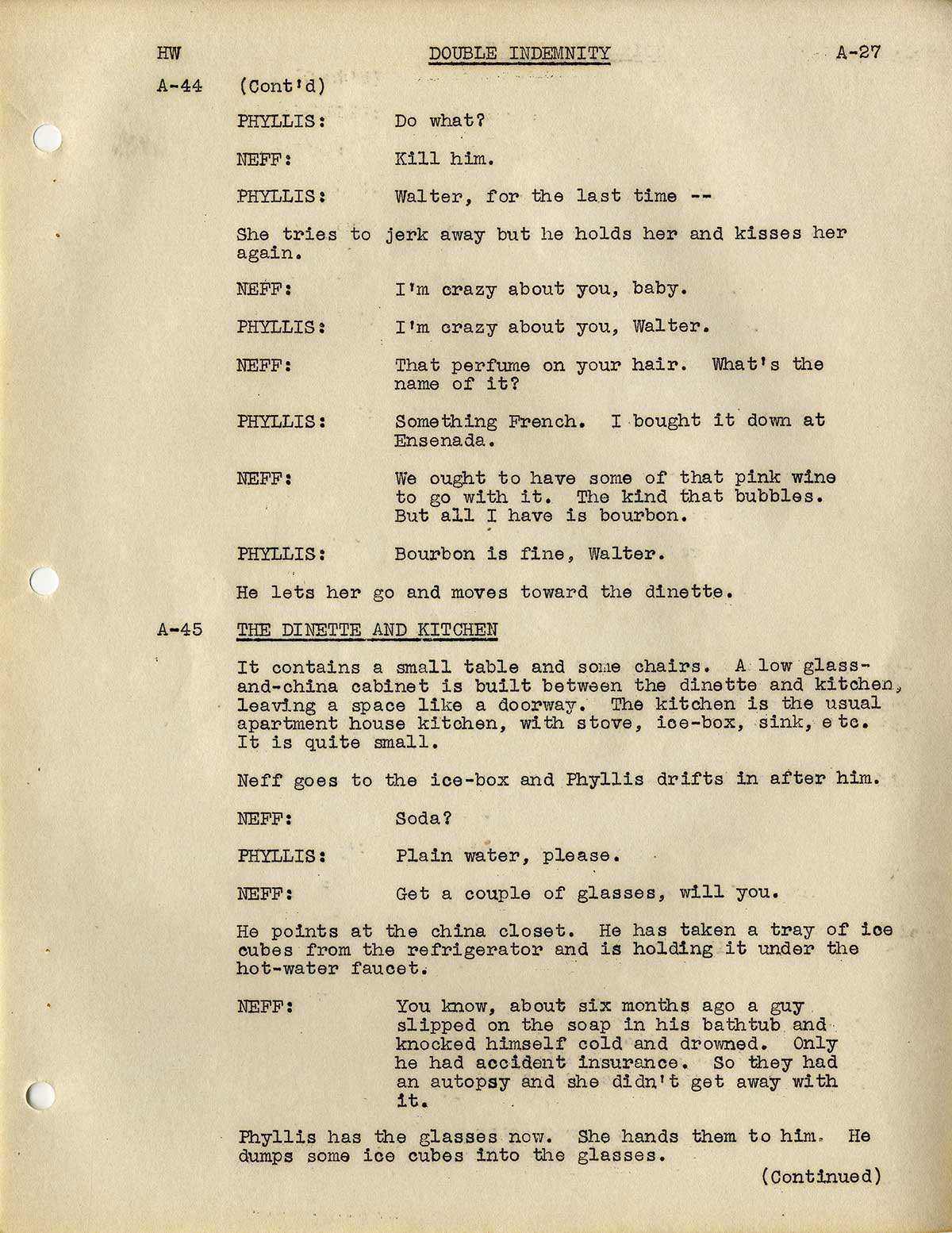

Chandler and Wilder’s clever screenplay structure gives us two interlocking character triangles. Triangle 1: Walter Neff, the salesman who thinks he’s smarter than he really is (MacMurray), Phyllis Dietrichson, the femme fatale who wants her husband murdered for his insurance money (Barbara Stanwyck), and Phyllis’s hapless husband. Triangle 2: Neff, Phyllis, and Neff’s best friend, who happens to be investigating the crime, Keyes. The relationship of Neff and Keyes is arguably the movie’s real love story.

Cain approved of the changes Chandler and Wilder made to his plot structure:

“Wilder’s ending was much better than my ending, and his device for letting the guy tell the story by taking out the office dictating machine – I would have done it if I had thought of it.”

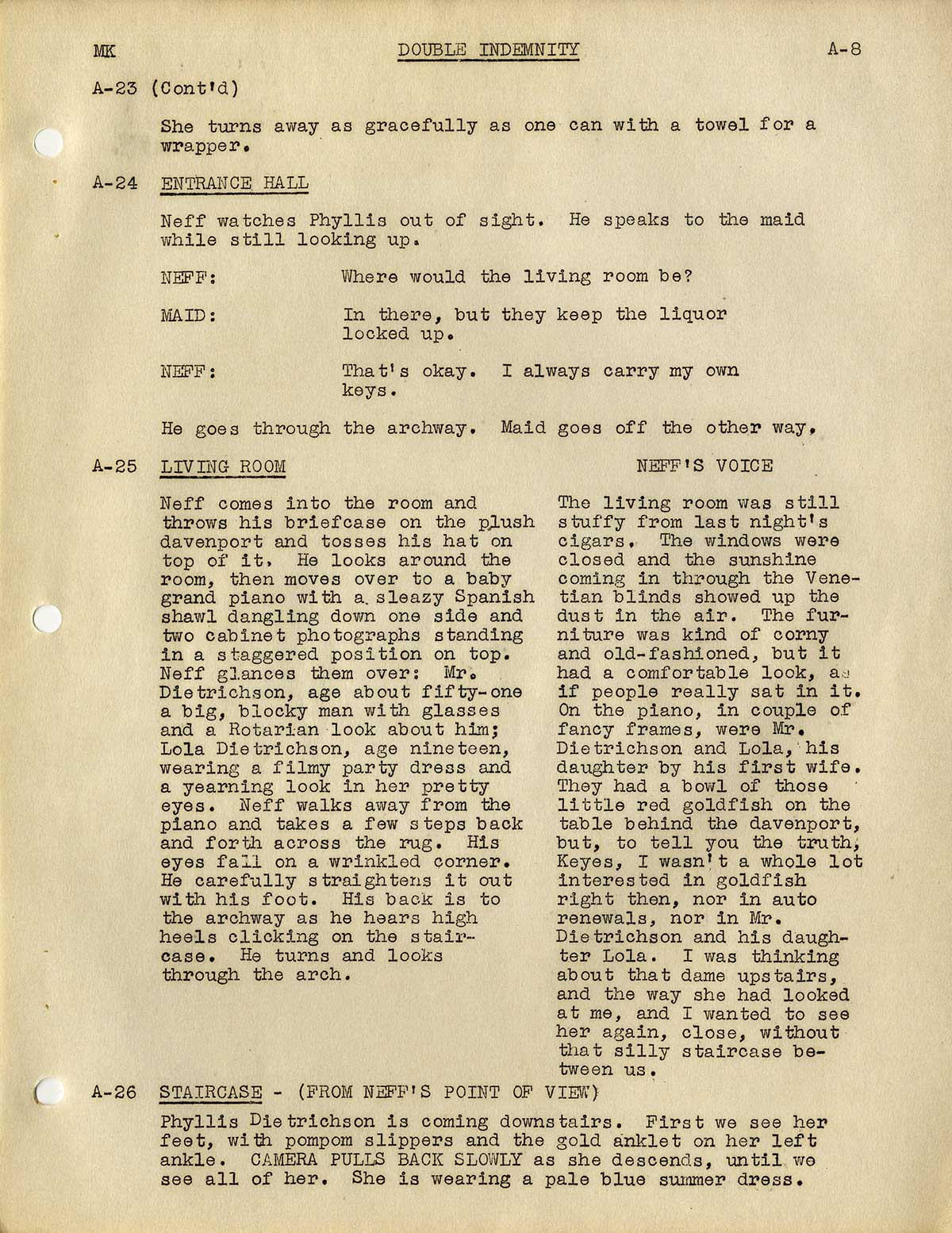

Cain’s dialogue was effective enough on the page, but apparently did not play well. Thus, Chandler’s other great contribution to the DOUBLE INDEMNITY screenplay was the sharpness of its Chandler-scripted dialogue. Consider this flirtatious exchange from Walter and Phyllis’s first meeting at her home (“Spanish craperoo in style,” per Chandler’s scene description), where Walter notices Phyllis’s gold anklet (a potent visual signifier of her sexual availability) and asks her what’s engraved on it:

PHYLLIS

Just my name.

NEFF

As for instance?

PHYLLIS

Phyllis.

NEFF

Phyllis. I think I like that.

PHYLLIS

But you’re not sure?

NEFF

I’d have to drive it around the block

a couple of times.

PHYLLIS

(Standing up again)

Mr. Neff, why don’t you drop by

tomorrow evening about eight-thirty.

He’ll be in then.

NEFF

Who?

PHYLLIS

My husband. You were anxious to talk

to him weren’t you?

NEFF

Sure, only I’m getting over it a little. If

you know what I mean.

PHYLLIS

There’s a speed limit in this state,

Mr. Neff. Forty-five miles an hour.

NEFF

How fast was I going, officer?

PHYLLIS

I’d say about ninety.

NEFF

Suppose you get down off your

motorcycle and give me a ticket.

PHYLLIS

Suppose I let you off with a warning

this time.

NEFF

Suppose it doesn’t take.

PHYLLIS

Suppose I have to whack you over the

knuckles.

NEFF

Suppose I bust out crying and put my

head on your shoulder.

PHYLLIS

Suppose you try putting it on my

husband’s shoulder.

The completed film version of DOUBLE INDEMNITY follows this Chandler/Wilder screenplay draft quite closely – including even the evocative screen descriptions written in Chandler’s distinctive voice. (Example: “They look at each other. The look is like a long kiss.“)

The biggest difference between the screenplay and the completed film is the legendary final scene – shot, but omitted from the final cut – of Neff’s execution in the gas chamber, witnessed by his friend, Keyes. Most film buffs agree that the ending of the film as it was released (Neff in the office, dying from a bullet wound, to Keyes: “I love you, too.”) is perfect as it is. However, in the “Alternate Ending” scripted by Chandler and Wilder, we see Neff marched into the gas chamber as Keyes watches. Neff is strapped into a chair. A lever is pushed to release the lethal cyanide gas. A doctor confirms Neff’s death. Keyes is the last to file out:

His hands, in the now familiar gesture, begin to pat his pockets for matches.

Suddenly he stops, with a look of horror on his face. He stands rigid, pressing a hand against his heart. He takes the cigar out of his mouth and goes slowly on towards the door, CAMERA PANNING with him. When he has almost reached the door, the guard stationed there throws it wide, and a blaze of sunlight comes in from the prison yard outside.

Keyes slowly walks out into the sunshine, stiffly, his head bent, a forlorn and lonely man.

FADE OUT

THE END

Out of stock

Related products

-

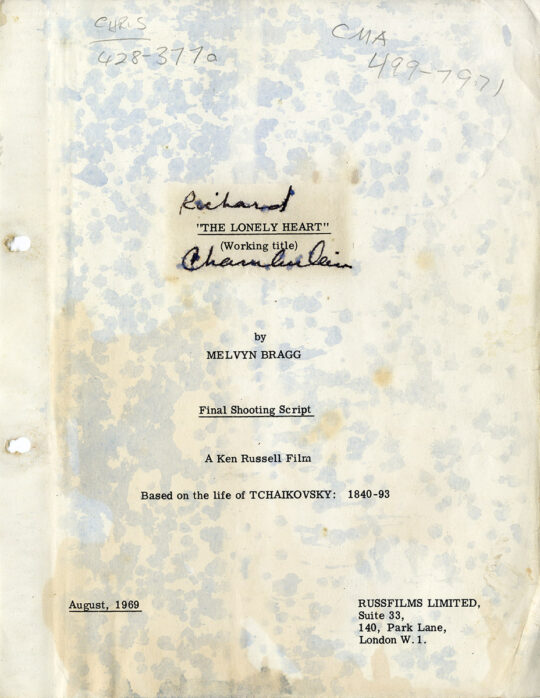

Ken Russell (director) THE MUSIC LOVERS [working title: THE LONELY HEART] (1969) Final shooting script

$3,000.00 Add to cart -

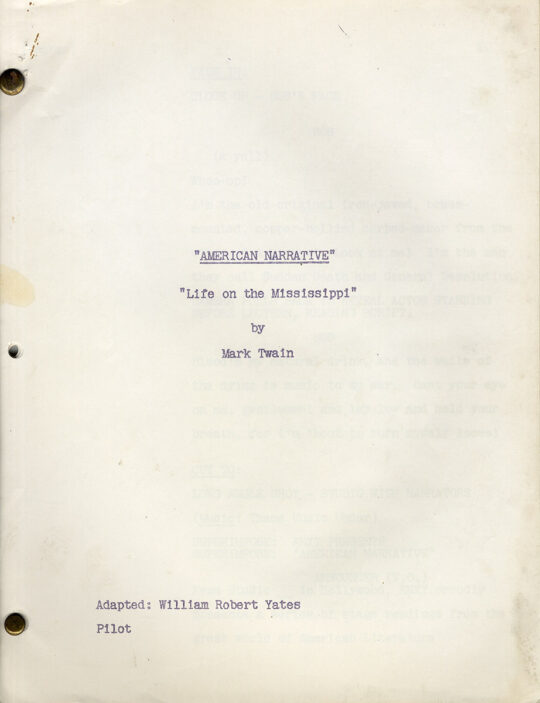

Mark Twain (source) LIFE ON THE MISSISSIPPI (ca. 1956) TV script adapted by William Robert Yates

$300.00 Add to cart -

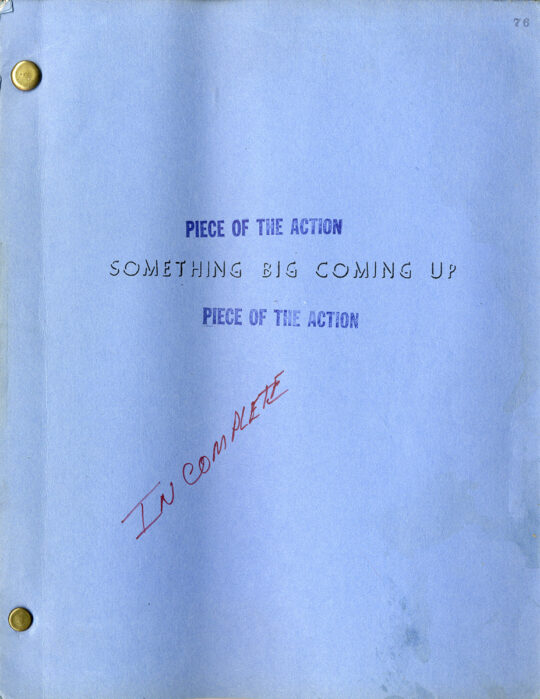

(African American film) A PIECE OF THE ACTION [working title: SOMETHING BIG COMING UP] (Nov 1, 1976) Film script

$750.00 Add to cart -

![MON ONCLE D'AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French screenplay](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/MonOncleDAmeriqueFR-SCR_a-540x745.jpg)

Alain Resnais (director) MON ONCLE D’AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French film script

$2,500.00 Add to cart