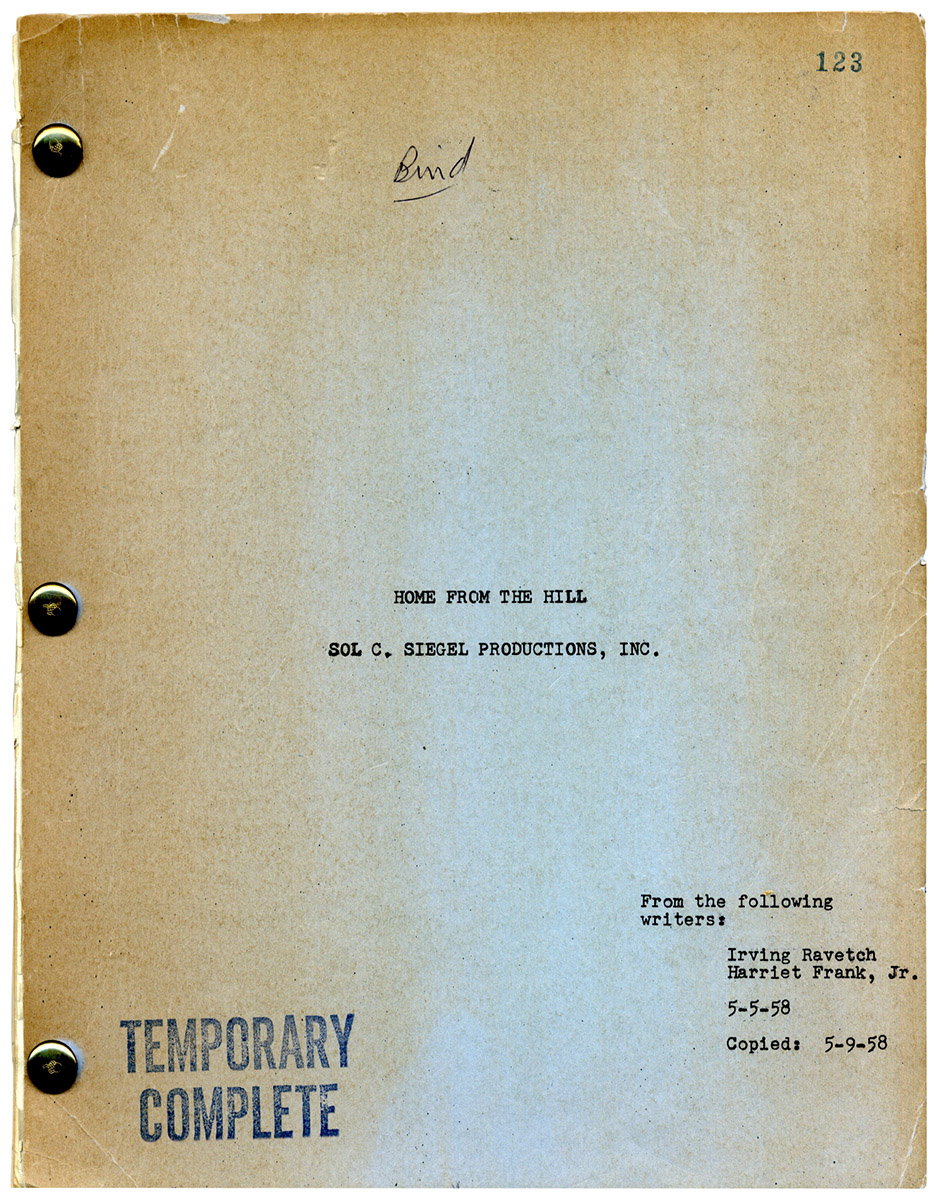

HOME FROM THE HILL (May 5, 1958) Temporary complete film script

Vincente Minnelli (director) [Los Angeles: Sol Siegel Productions], 1958. Vintage original film script, 11 x 8 1/2″ (28 x 22 cm.), [2], 152, [1] pp. Gray titled wrappers, brad bound, mimeograph, small tear and light scattered tanning to front wrapper, fine in near fine wrappers.

Irving Ravetch (1920-2020) and Harriet Frank Jr. (1923-2020) were an Academy Award-nominated screenwriting couple best known for a their three-decade collaboration with director Martin Ritt, including the screenplays for HUD (1963), HOMBRE (1967), NORMA RAE (1979), MURPHY’S ROMANCE (1985), and STANLEY AND IRIS (1990). They were apparently selected to adapt William Humphrey’s Texas-based novel, HOME FROM THE HILL, based on the strength of the two William Faulkner adaptations they had scripted for Ritt, THE LONG HOT SUMMER (1958) and THE SOUND AND THE FURY (1959). Vincente Minnelli, who directed HOME FROM THE HILL, said it was “one of the few film scripts in which I didn’t change a word.”

Like George Stevens’ GIANT (1956), HOME FROM THE HILL is an epic family melodrama set in modern-day Texas. It was one of a series of epic melodramas directed by Minnelli for MGM in the late ’50s and early ’60s, also including SOME CAME RUNNING (1958) and THE FOUR HORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE (1962).

However, the Minnelli film that most resembles HOME FROM THE HILL, thematically speaking, is his 1956 adaptation of the Broadway play, TEA AND SYMPATHY. Like TEA AND SYMPATHY, HOME FROM THE HILL is a story about a sensitive (some would say effeminate) young man in conflict with a world of toxic masculinity. Some have read TEA AND SYMPATHY as a kind of apologia for Minnelli’s own perceived effeminacy. HOME FROM THE HILL takes the theme much further in that all of the movie’s main characters are seen to be victims, in one way or another, of their community’s macho “code.”

HOME FROM THE HILL’s three principal characters are a wealthy Texas patriarch, Captain Wade Hunnicutt (Robert Mitchum), his “sensitive” legitimate son, Theron (George Hamilton), and his illegitimate son, Theron’s half-brother, Rafe (George Peppard). One of the remarkable things about the screenplay is that the character of the illegitimate son, Rafe — in many ways the film’s moral center — was a creation of the screenwriters Ravetch and Frank.

The screenplay announces its themes from the very start. It begins with Wade (Mitchum) in the wilderness hunting geese with his unacknowledged bastard son, Rafe (Peppard), when he is unexpectedly shot, not fatally, by another man who rightfully believes Wade has been sleeping with his wife. The doctor who treats Wade’s wound lays it all out for us:

CARSON

I’ll tell you where we small town Texans get our name

for violence. It’s grown men like you still playing guns

and cars. You never grow out of it. A man isn’t a man

around here unless he uses up a car a year, goes down

the road at a hundred miles an hour, owns six or seven

fancy shotguns, knows six or seven fancy ladies.

As noted, all three of the screenplay’s protagonists are the victims of this ideology. Wade is shot dead, not by the husband of someone he slept with, but, ironically, by the father of the girl, Libby, who his son Theron impregnated, a man who mistakenly believes that Wade was responsible. Theron’s fate is arguably even more tragic, going into self-imposed exile after impregnating his girlfriend and killing her father (Everett Sloane) in revenge for the death of his own. Indeed, all of Theron’s actions following his rite of passage from ‘boy’ to ‘man’ are socially conditioned, and he never acquires a true identity of his own. Rafe, the bastard, after — Christ-like — taking on the “sins” of his father and half-brother (i.e., by marrying the girl his half-brother impregnated) finally gets to see his status as son acknowledged on his father’s tombstone, but he never received that acknowledgment while his father was alive.

Ravetch and Frank’s screenplay is structured brilliantly around four hunting sequences. The first, already described, is the movie’s opening scene in which Wade is non-fatally wounded while hunting geese with Rafe. The second is the often-discussed “snipe hunt” scene where naïve young Theron is humiliated by the men of the town who send him off into the woods to hunt a nonexistent bird. The third is the story’s big coming-of-age scene in which Theron, after being trained how to hunt by his father and Rafe, successfully tracks down and kills a wild boar. The last, which echoes the other three, is the movie’s penultimate scene in which Theron tracks down and kills the man who murdered Wade — who turns out to be his girlfriend’s father (and therefore the grandfather of Theron’s child).

While Minnelli claims not to have changed a word of Ravetch and Frank’s screenplay, he did, in fact, substantially cut it. Not only is the dialogue trimmed in most scenes, but a number of scenes were cut altogether. For example:

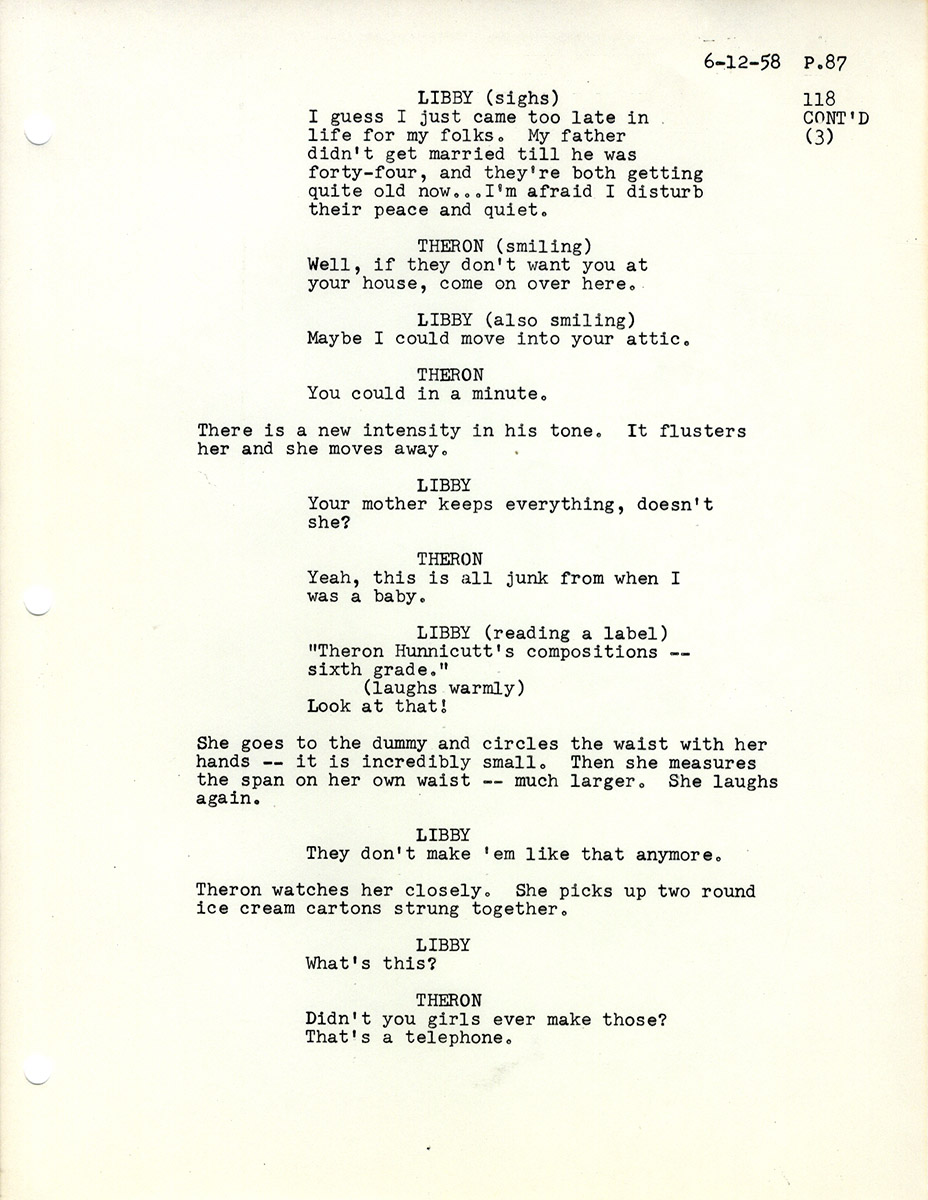

- A soda fountain scene with Theron, Libby, and one of her girlfriends, a scene that introduces Libby, establishes Theron’s attraction to her and his fundamental shyness.

- A scene where Rafe teaches Theron how to hunt squirrels.

- A scene where Melba, the family’s black cook, offers to use magic to help Theron with his girlfriend.

- A dialogue scene between Wade and one of his lovers, the town whore, taking place at the barbecue that celebrates Theron’s killing of the boar. In the movie, Minnelli establishes their relationship wordlessly with a glance.

- A scene between Rafe and Theron’s mother, Hannah (Eleanor Parker), that establishes the animosity between them, an animosity that will be reconciled in the movie’s final scene.

- Libby and Rafe’s marriage by a justice of the peace.

- A scene in which Theron secretly witnesses the baptism of his biological son after the marriage of Libby and Rafe. This scene echoes an earlier monologue by Rafe in which he described the feelings he had as a little boy outsider watching the baptism of Theron.

While the completed film runs 2 hours and 30 minutes, if the omitted scenes had been included it would very likely have run longer than 3 hours.

This script, although it bears a date of 5-5-58 on its front wrapper, is filled with revisions. After page 76, all the rest of the script is composed of revision pages, some on yellow revision paper, dated up through 6-20-58.

Out of stock

Related products

-

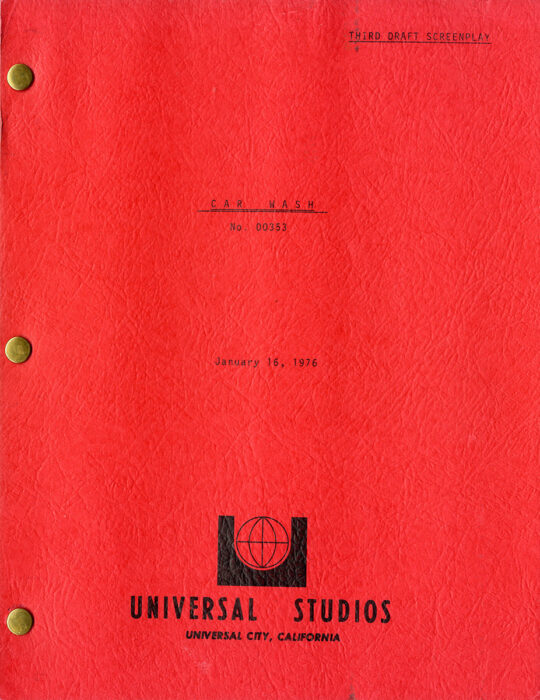

(African American film) CAR WASH (1976) Third draft film script by Joel Schumacher

$850.00 Add to cart -

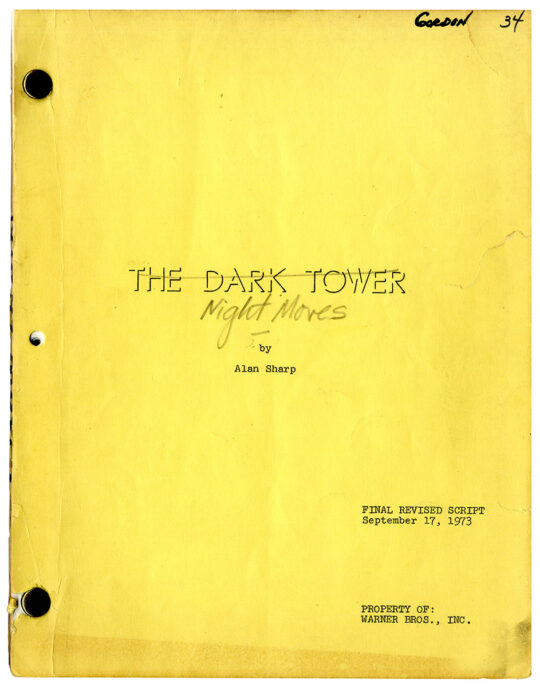

Arthur Penn (director) NIGHT MOVES [working title: THE DARK TOWER] (Sep 17, 1973) Final revised film script

$2,000.00 Add to cart -

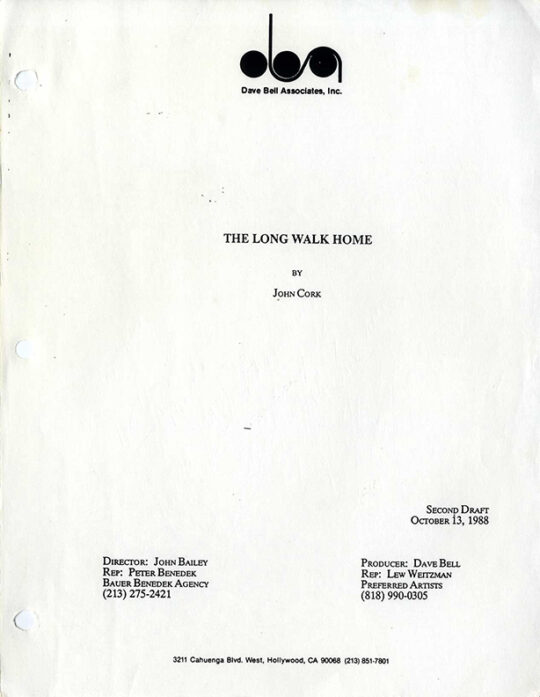

LONG WALK HOME, THE (Oct 13, 1988) Second draft film script by John Cork

$375.00 Add to cart -

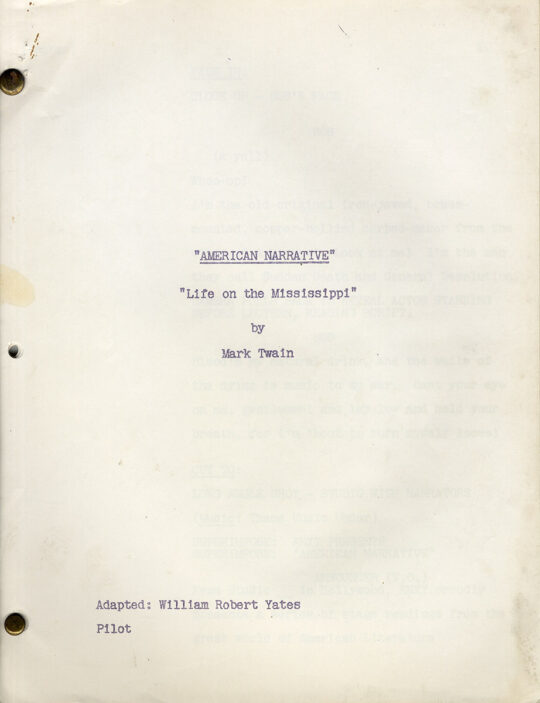

Mark Twain (source) LIFE ON THE MISSISSIPPI (ca. 1956) TV script adapted by William Robert Yates

$300.00 Add to cart