SLEEP ON THE ROOF (1967) Unproduced script based on the life of Margaret Sanger

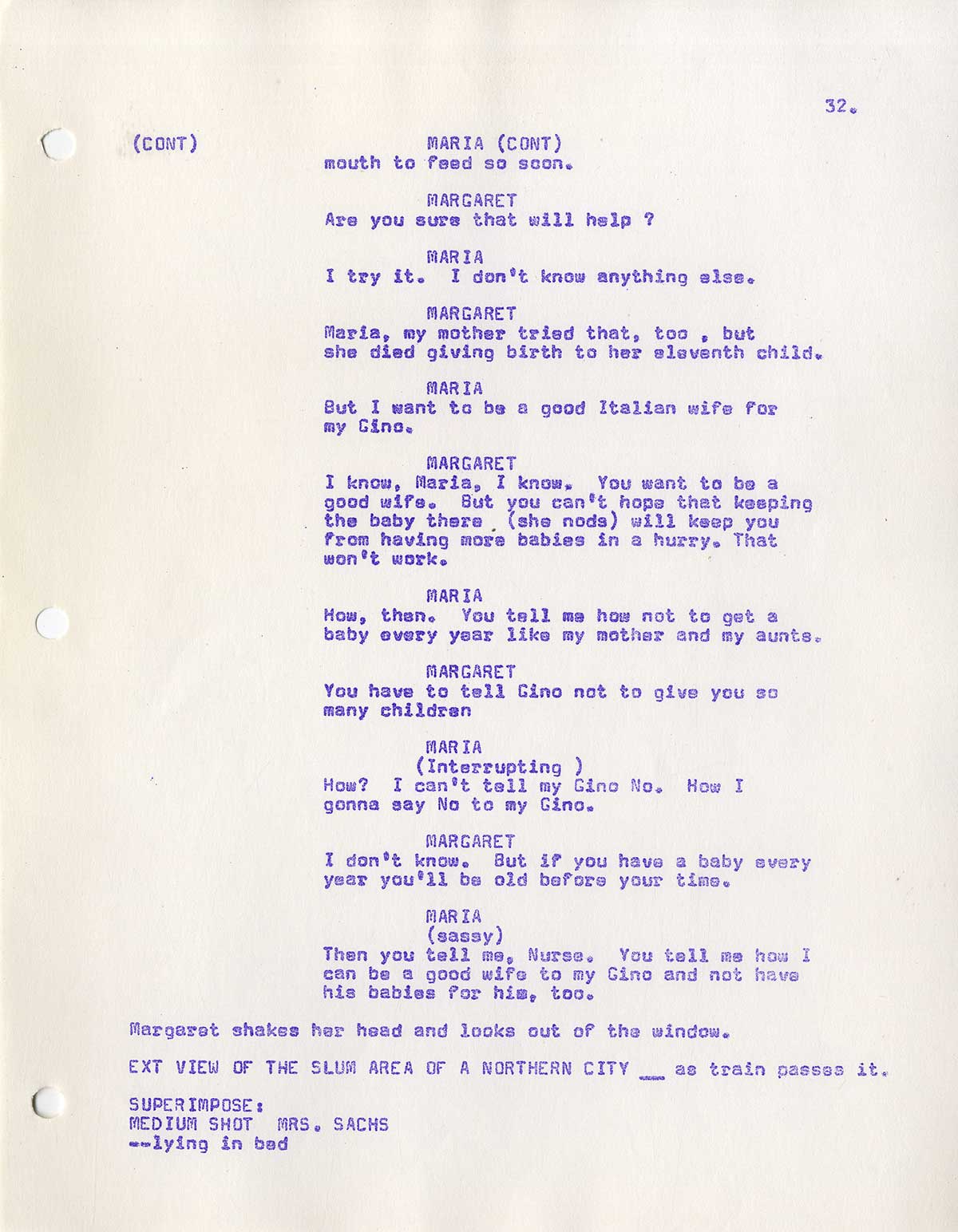

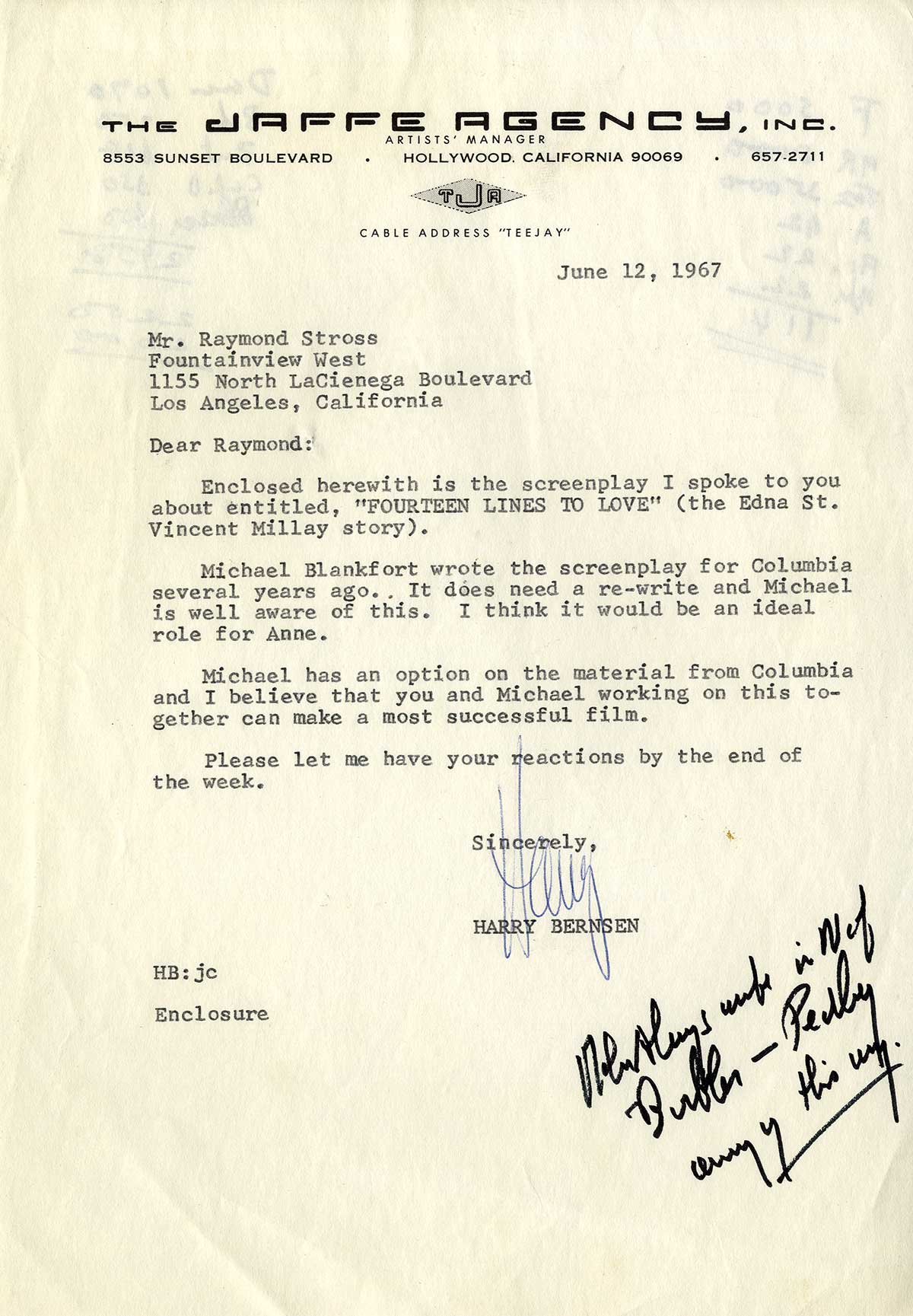

Margaret Sanger (subject) Story and Screenplay by Marcia F. Cohen dated May 19, 1967. Vintage film script, quarto. 128 pp., in plain stiff wrappers, bolt bound, with typed label affixed. Mimeograph on blue paper, with some scattered MS revisions in Cohen’s hand, and a few pages of revisions on onionskin paper, VERY GOOD.

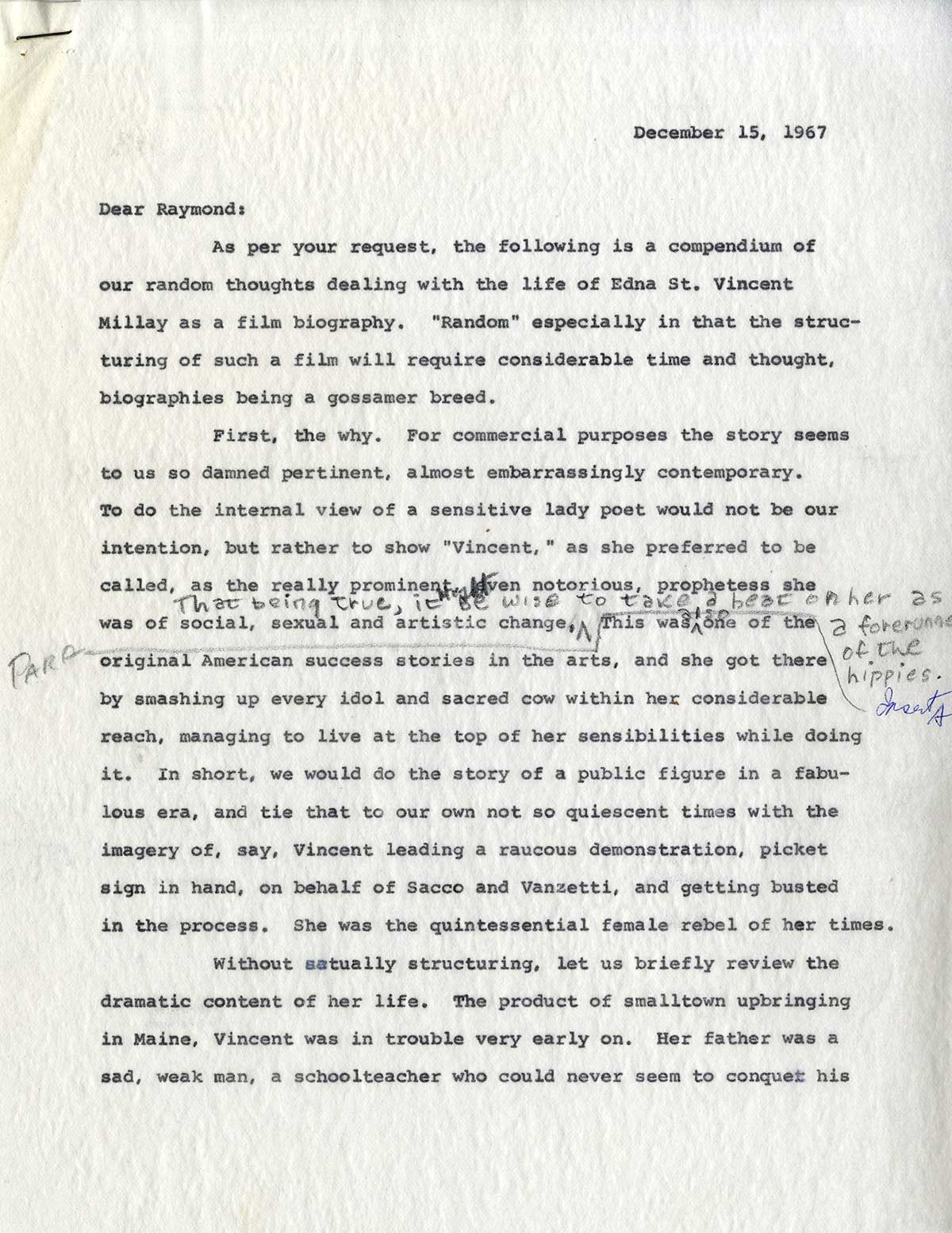

An unproduced screenplay for the life of Margaret Sanger.

Margaret Sanger (1879-1966) was an American nurse who became a birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and speaker. She opened the first birth control clinic in the United States and later established the organizations that evolved into Planned Parenthood. She is credited with popularizing the term “birth control.”

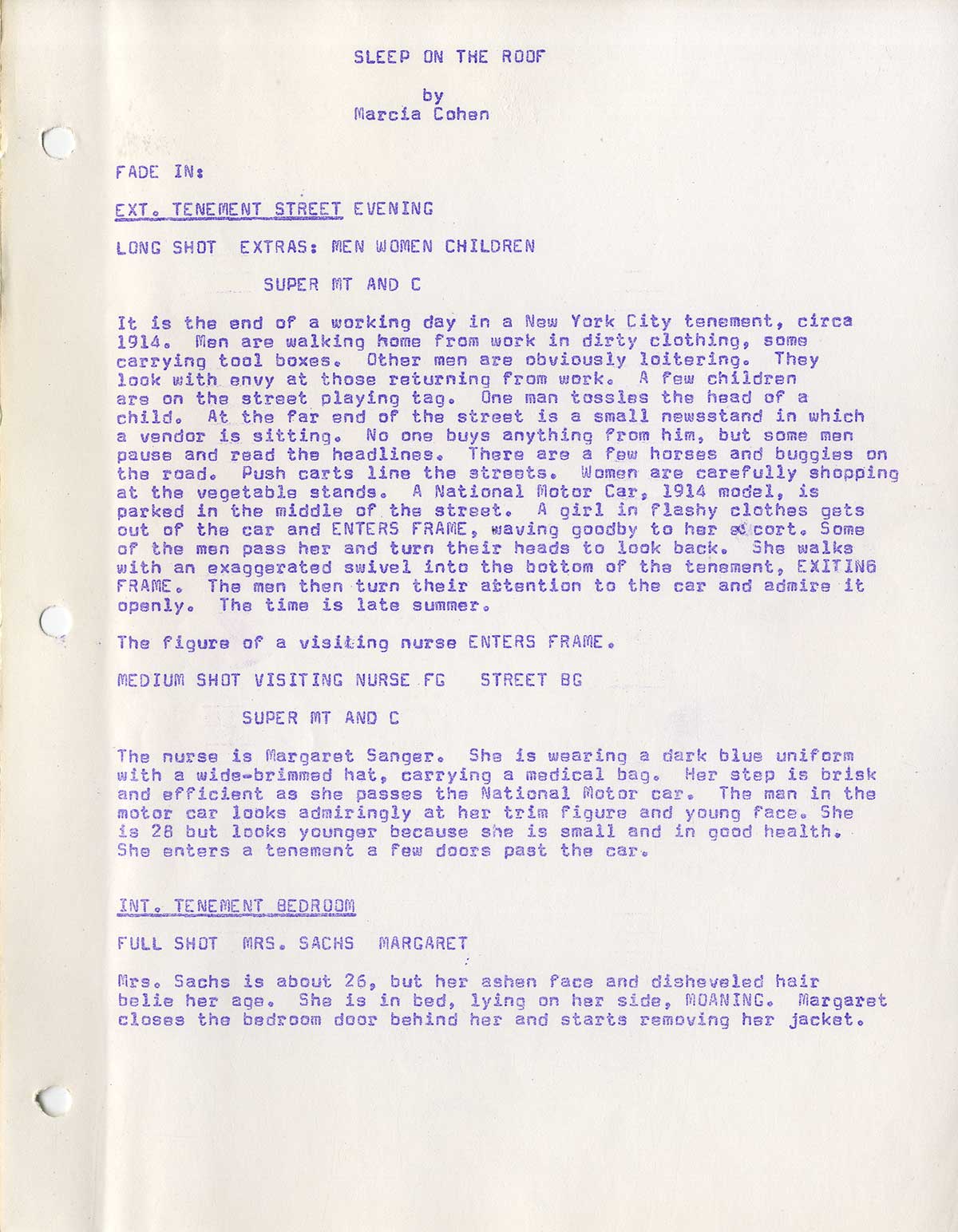

Marcia Cohen’s screenplay dramatizes Sanger’s life from roughly 1914 through 1916, the period when she first became a public figure. The screenplay begins in a New York City tenement in 1914 where young nurse, Margaret Sanger, is treating a married woman who is dying due to a self-administered abortion. The dying mother, a European immigrant, asks a doctor who is present if there is any way she can prevent another pregnancy, so that there will be, “No more babies for my Jake to feed.” The doctor responds:

For one thing, you could tell Jake to sleep on the roof!

Hence, the screenplay’s title. We learn that during this period it was illegal for doctors to give contraceptive advice: “Not one word. It’s against the law.”

The death of the young immigrant mother due to an abortion is an incident that impresses Margaret deeply, and we flash back to it several times during the course of this screenplay.

In the following scene, we meet the story’s principal antagonist, Anthony Comstock (1844-1915), a United States Postal Inspector and secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, who is dedicated to upholding Victorian morality. Part of his crusade as a Postal Inspector is to suppress the distribution of any material that refers, in even the most oblique manner, to the sexual act.

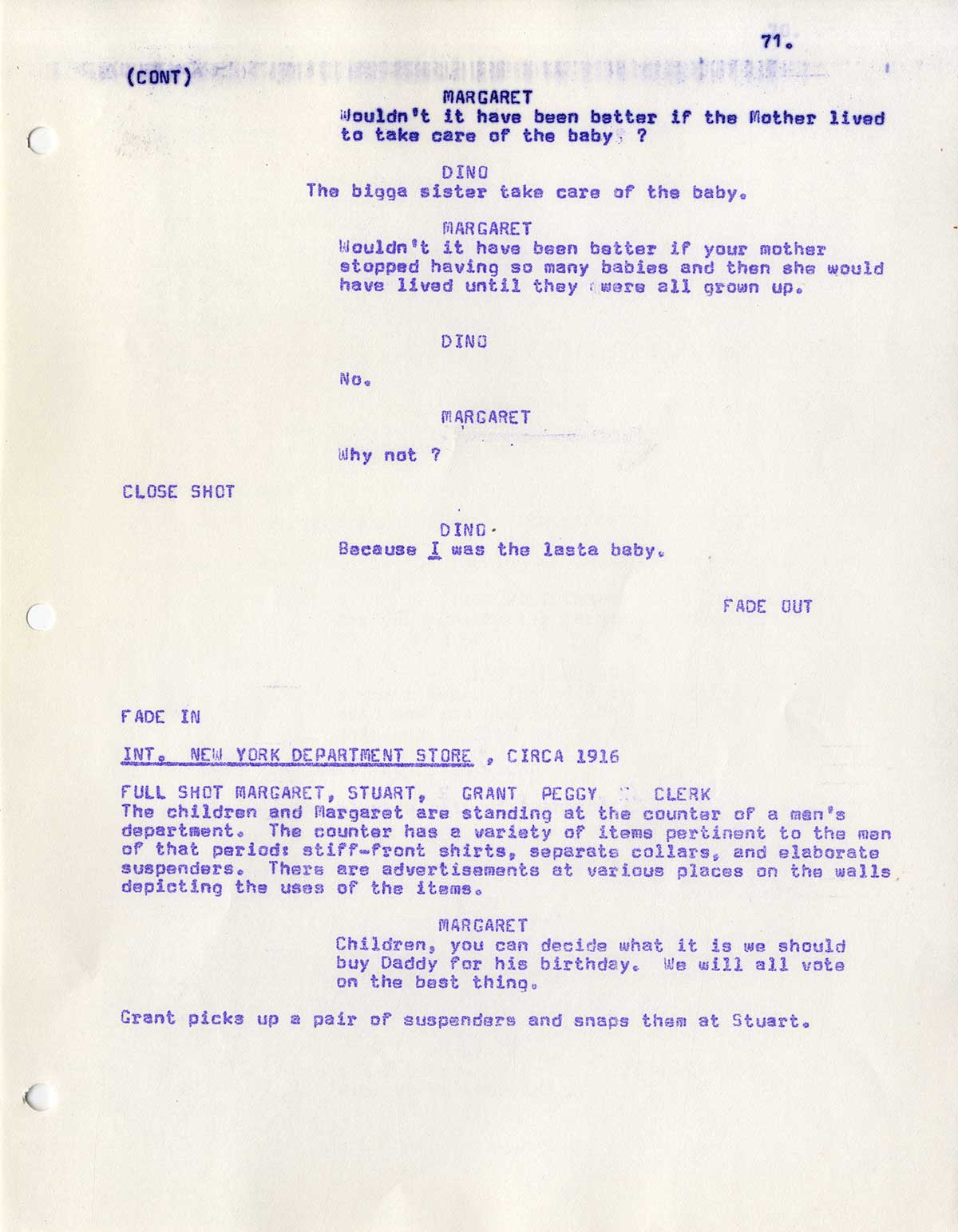

Next, we meet Margaret’s family: her husband, Bill Sanger, a successful architect, and her children, Stuart, Grant, and Peggy. We see Margaret preparing to make love:

Margaret reaches up on the bathroom shelf for the diaphragm container. She unwinds the top.

FILTERED SHOT

Through the shadow of the curtain the CAMERA REVEALS Margaret —in shadow— bending over and inserting the diaphragm. She lifts her leg to the toilet seat and bends her arm toward her pelvis.

Margaret’s public life begins when her friend Anita, a magazine editor, invites her to write a column for the “number one woman’s magazine,” THE CALL:

I want you to teach the women of America. how to be better mothers and how to keep up the health of their families.

As a nurse, Margaret continues to be asked by the slum women she treats how they can please their husbands without becoming pregnant again. During a strike, Margaret, Anita, and other activist women set up a service to feed the children of the striking workers. Margaret observes the problem of families with too many children and not enough income to feed them – with children as young as 7 being forced to work jobs to help support their families. This leads to a series of cover-featured articles in THE CALL:

FEB. WHAT EVERY GIRL SHOULD KNOW: THE SEX FUNCTION

MAR. WHAT EVERY GIRL SHOULD KNOW: ABORTION

And after Postal Inspector Comstock becomes aware of what they are doing:

APRIL WHAT EVERY GIRL SHOULD KNOW:

N

O

T

H

I

N

G

!

By Order of the

POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

Since the CALL magazine can’t get any more explicit about contraception without being shut down, Margaret does something even more radical. She withdraws all the money from her and her husband’s joint bank account and takes it to a private printer in order to publish a monthly newsletter THE WOMAN REBEL, promoting contraception, which in turn directs its readers to a pamphlet called FAMILY LIMITATION that is a factual how-to guide concerning birth control (describing the “rhythm method” and the use of diaphragms).

Inevitably, what Margaret is doing becomes associated with the other feminist movements happening at this point in history, equality and women’s suffrage, even though Margaret herself says:

I am not a suffragette. I am a nurse.

Margaret’s husband William does not approve of what she is doing – is doubly shocked when she withdraws all of their money for her cause – yet he continues to love and support her personally. Margaret is subpoenaed to appear in court. While she is in Holland, gathering information on Dutch methods of birth control, her disapproving husband is caught in a sting operation by Postal Inspector Comstock – there are copies of Margaret’s “obscene” pamphlets in their home – and is jailed. Margaret and her friends open up what is essentially the world’s first birth control clinic.

Eventually, Margaret herself goes on trial. What to her was fundamentally an issue of health and combating the evils of poverty has now become a free speech issue. Does Margaret have the right to print and say what she has been printing and saying? There is a lengthy courtroom scene in which Margaret’s ideas are debated, and the screenplay concludes with Margaret being found guilty and sentenced for thirty days to the workhouse.

In fact, this was just the beginning of Margaret Sanger’s multi-decade career as a birth control activist. In later years, she would remarry – a man named Noah Slee who became the first legal manufacturer of diaphragms in the United States – and she would found the organization that became “Planned Parenthood”.

Marcia Cohen’s screenplay, SLEEP ON THE ROOF, is an effective dramatization of Sanger the activist’s early years.

In stock

Related products

-

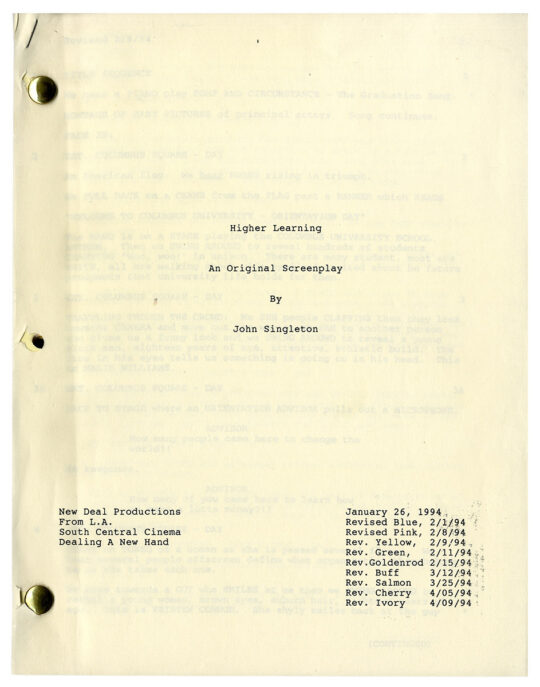

John Singleton (writer, director) HIGHER LEARNING (Jan 26, 1994) Rainbow film script

$500.00 Add to cart -

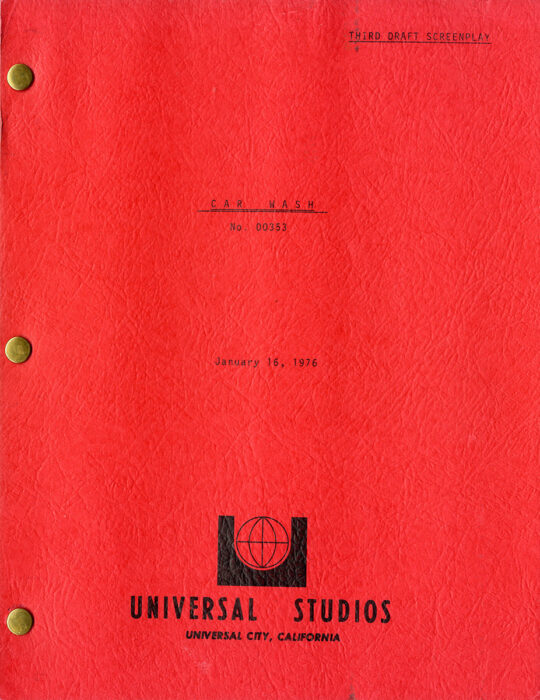

(African American film) CAR WASH (1976) Third draft film script by Joel Schumacher

$850.00 Add to cart -

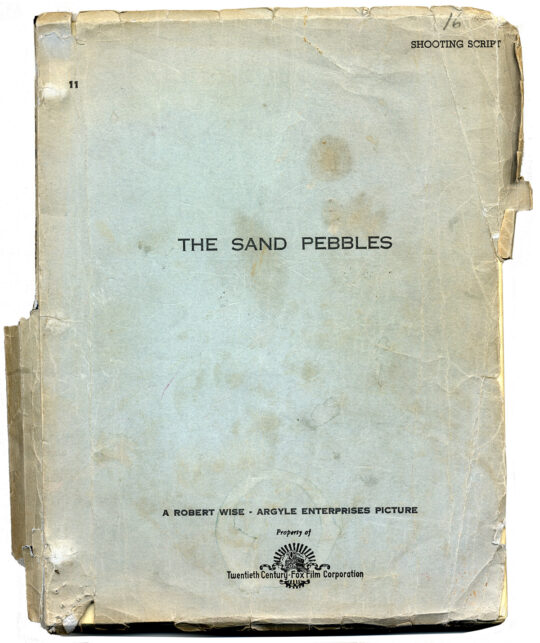

SAND PEBBLES, THE (Nov 1, 1965) Shooting script by Robert Anderson

$1,150.00 Add to cart -

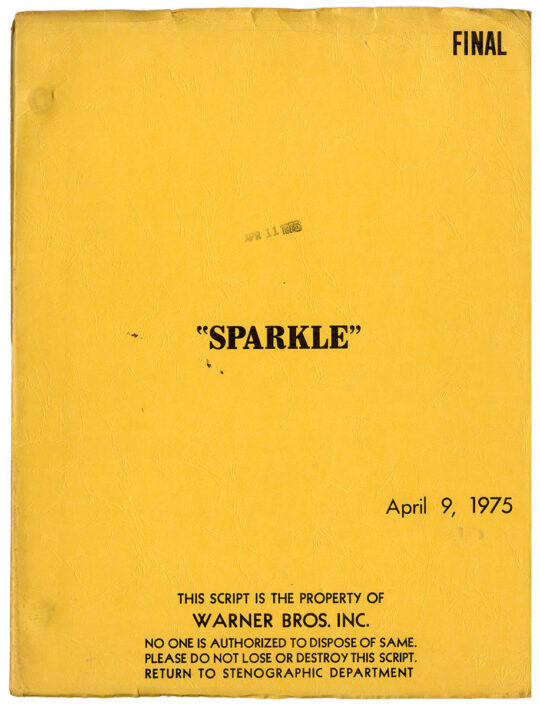

(Blaxploitation film) SPARKLE (Apr 9, 1975) Final Draft film script by Joel Schumacher

$750.00 Add to cart