Billy Wilder (screenwriter, director) STALAG 17 (1951-52) Script archive including Wilder’s extensive holograph revisions

[Hollywood: Paramount Pictures, 1951-2]. Vintage original film script archive, quarto (with 1951 script bound into folio plain folder). consisting of:

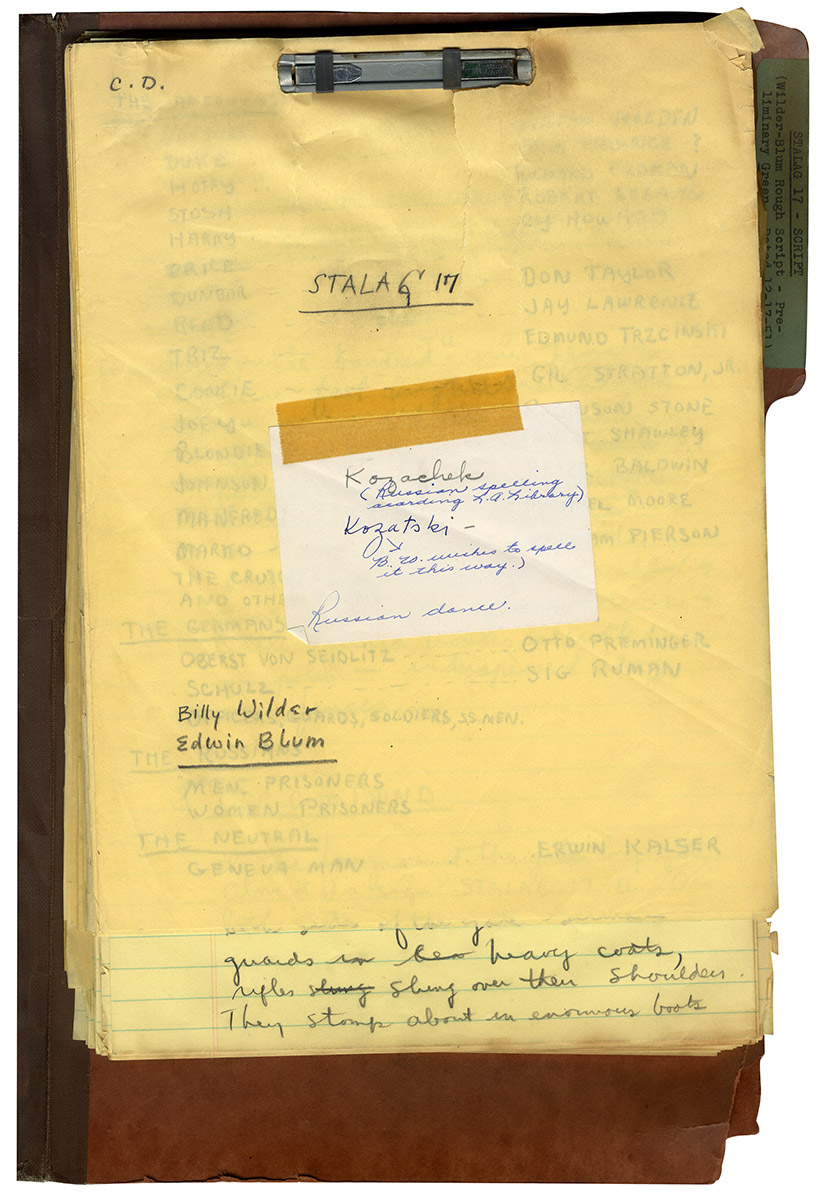

—Handwritten draft dated December 17, 1951. Mostly handwritten in pencil, but also incorporating several pages of typewritten script that have been heavily crossed out and rewritten in pencil, 118 pp., quarto. Tanning to the extreme blank edges (mostly visible on the blank backs of pages), scattered creasing. Bound into a blank folder with metal clasp at top. Generally very good or better.

—Set illustrations (pencil), 3 pp.

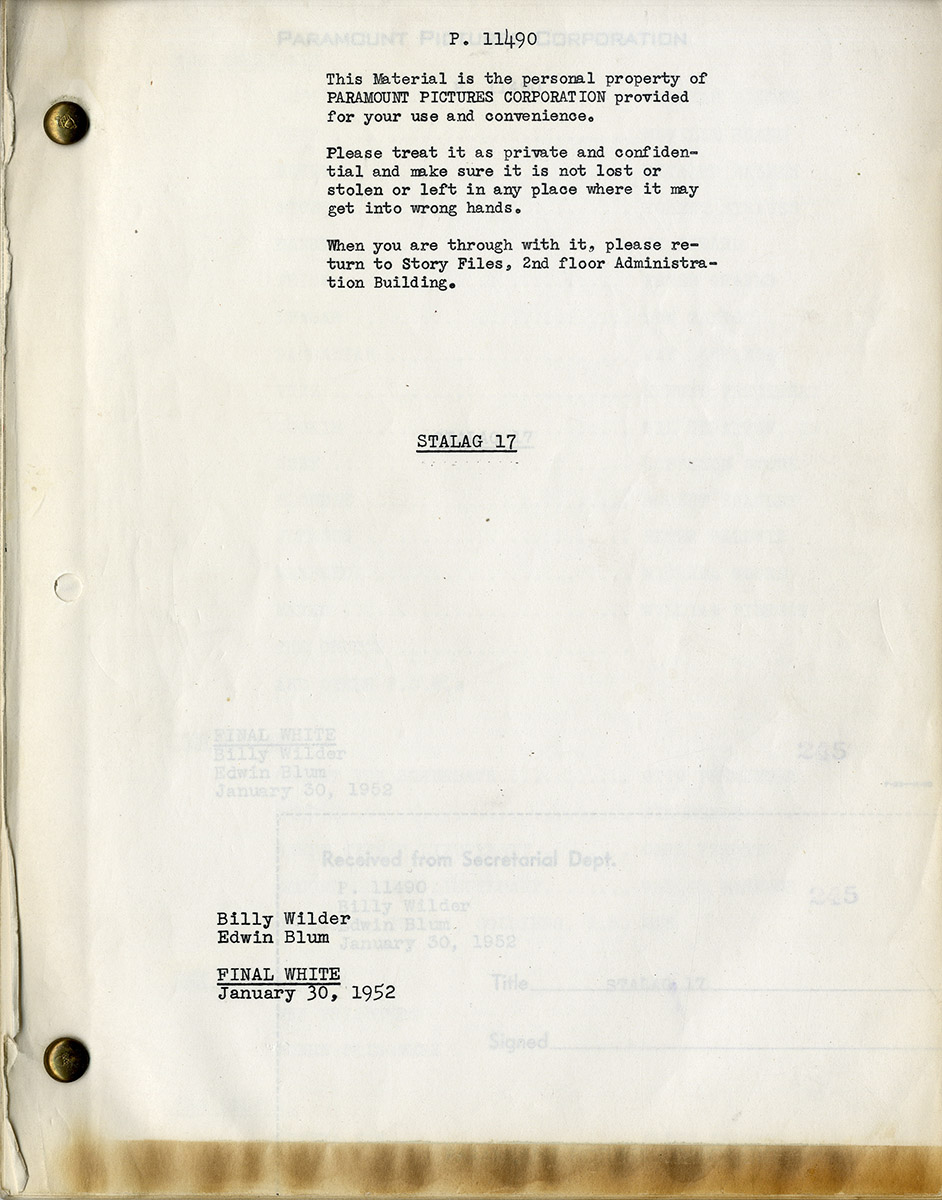

—Final White screenplay by Billy Wilder and Edwin Blum, dated January 30, 1952, 129 pp., self-wrappers, quarto, mimeograph, brad bound. Tanning at the blank bottoms of the first and last pages, overall near fine.

STALAG 17 can be considered the third film in an informal trilogy made by Billy Wilder in the early 1950s featuring cynical, opportunistic male protagonists. The first film in the trilogy, SUNSET BOULEVARD (1950), starring Gloria Swanson as a faded movie star and William Holden as the film’s cynical screenwriter protagonist, was a great critical and popular success, earning multiple Academy Award nominations and winning for Best Original Screenplay. The second film in the trilogy, ACE IN THE HOLE aka THE BIG CARNIVAL (1951), featuring Kirk Douglas as an opportunistic journalist, is perhaps the most cynical and misanthropic picture that Wilder ever made. It was a critical and box office disaster.

After the failure of ACE IN THE HOLE, producer/director Wilder played it safer with his next project, STALAG 17 (1953). The screenplay was adapted from a successful Broadway play written by Donald Bevan and Edmund Trzcinski, based on their war-time experiences as prisoners in an actual Austrian Stalag. This time around, Wilder and his co-screenwriter Edwin Blum chose to emphasize the story’s comic aspects and play down its darker side, reserving most of their vitriol for the Germans who run the prison camp. Once again, William Holden was cast as the cynical opportunistic lead, and once again Holden retained the audience’s sympathy as he had done in SUNSET BOULEVARD, this time winning the Academy Award for Best Actor.

The screenplay of STALAG 17 is nonetheless a daring mixture of dark and light tones. It begins with the grisly death of two American soldiers, machine-gunned while attempting to escape from the camp, and ends with a successful escape. In between, there are scenes of prisoners enduring hunger, cold, and, in one case, torture. Though Holden’s character is the nominal lead, the story is truly an ensemble piece, with each of the main prisoner characters vividly defined and some of them getting as much or more screen time as Holden gets. It was director/writer Wilder’s first collaboration with screenwriter Edwin Blum (DOWN TO EARTH, THE CANTERVILLE GHOST), after making five films in a row with producer/writer Charles Brackett, and since Wilder and Blum had a particularly abrasive relationship during the writing of STALAG 17, it would prove to be their last.

What drives the screenplay’s story is the mystery of who among the prisoners is an informant, telling the Germans everything they need to know about the prisoners’ escape plans. Since Holden’s character, Sefton, a natural-born hustler, has been making a pretty good living as a prisoner running rackets for the other prisoners like gambling and a distillery, and is generally considered to be out for himself alone, the other prisoners wrongly assume that he is the informant and beat him nearly to death based on that suspicion. This is Wilder’s oblique criticism of the McCarthy Era when anyone could be considered “guilty by suspicion”, and it is the heart of the film.

The darker aspects of the story are balanced by the broad comedy provided by the two clowns of the ensemble, Robert Strauss as “Animal”, defined by his outlandish appetite for food and “broads”, and Harvey Lembeck as Harry, Animal’s self-appointed keeper. Strauss and Lembeck had played these same roles in the original Broadway production of the play which Wilder had probably seen. Among the pair’s more memorable antics — Harry and Animal, carrying a bucket of paint and a brush, paint a white line down the middle of the road leading toward the Russian compound and conveniently make a sharp turn directly toward the shack where the Russian women prisoners are being deloused. They make it as far as the steamed-up window of the delousing shack. When caught in the act by a German guard, they quickly paint over his glasses and scamper away madly like Laurel and Hardy or the Three Stooges. This is not something that the two of them could have done on stage, where all the action was confined to a barrack. Though Wilder as a writer was known primarily for his verbal wit, the screenplay has more than its share of visual humor. A scene with Harry in semi-drag foreshadows the cross-dressing in SOME LIKE IT HOT.

While the play was significantly expanded and altered in its transition from stage to screenplay, there are almost no significant differences, aside from a few cut lines, between this “Final White” screenplay and the movie that was made from it. It is virtually a shooting script. STALAG 17 was a critical and popular success, establishing a template for the further Wilder hybrids of comedy and drama that were to come.

EARLIER HANDWRITTEN DRAFT

This is an earlier draft, dated December 17, 1951, of Billy Wilder and Edwin Blum’s STALAG 17 screenplay, mostly handwritten in pencil on lined yellow paper. The handwriting is clearly Wilder’s. It also incorporates 40 or more pages of typewritten film script which have been heavily crossed out and rewritten.

It begins with a hand-printed cast list which is mostly, but not entirely, the same actors who appear in the film. William Holden is at the top of the list as Sefton, but this list also shows Jack Palance (with a question mark) as Duke, a part that was played in the film by Neville Brand. Likewise the list indicates Cy Howard as Harry, a part eventually played by Harvey Lembeck. Edmund Trzcinski, cast as “Triz”, was one of the authors of the original Broadway play based on his own P.O.W. experiences..

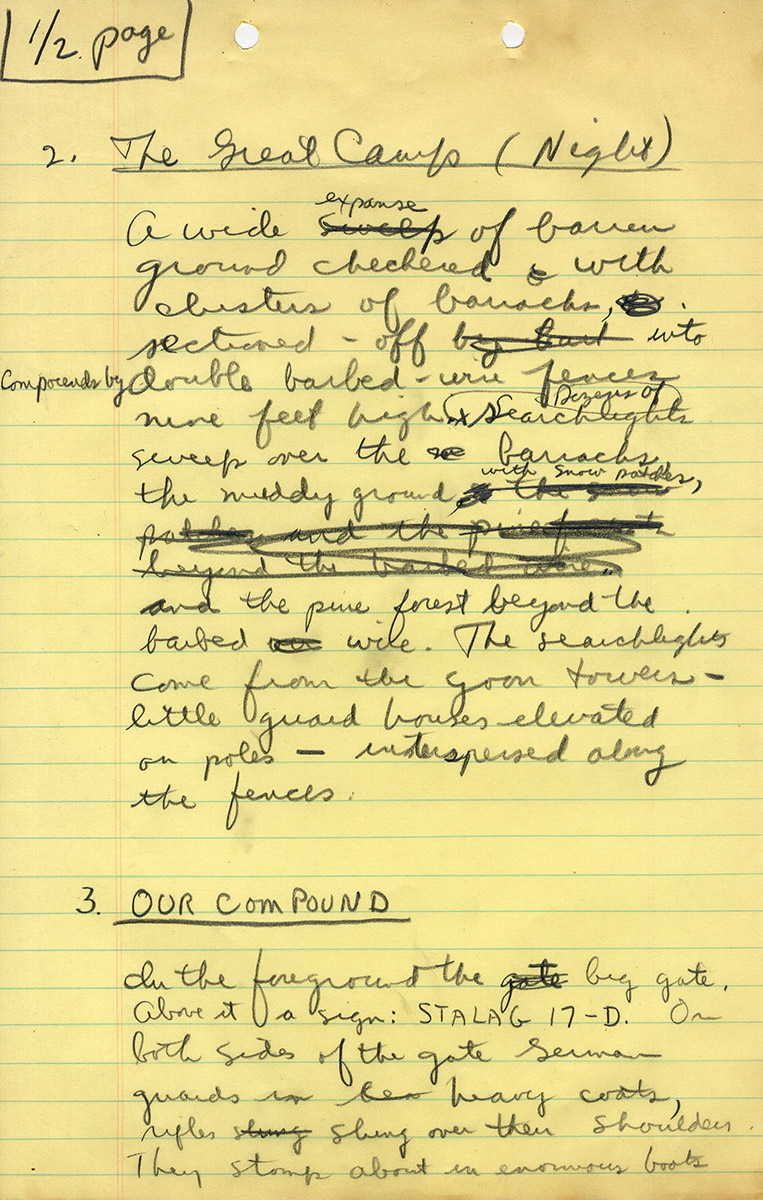

This handwritten draft begins, like the “Final White” screenplay with detailed descriptions of the camp and then the barracks, but unlike the “Final White” screenplay, these descriptions are not broken down into separate shots. Unlike the “Final White” screenplay, there is no indication of voiceover narration. After four pages of handwritten action description and virtually no dialogue, there is a page of typewritten description in script form which does have a column of Cookie’s (Gil Stratton, Jr.’s) voiceover narration — also typewritten — scotch-taped to it. (The narration has the penciled annotation “borinnnnng!” but it is more or less the same voiceover narration we hear in the completed film.)

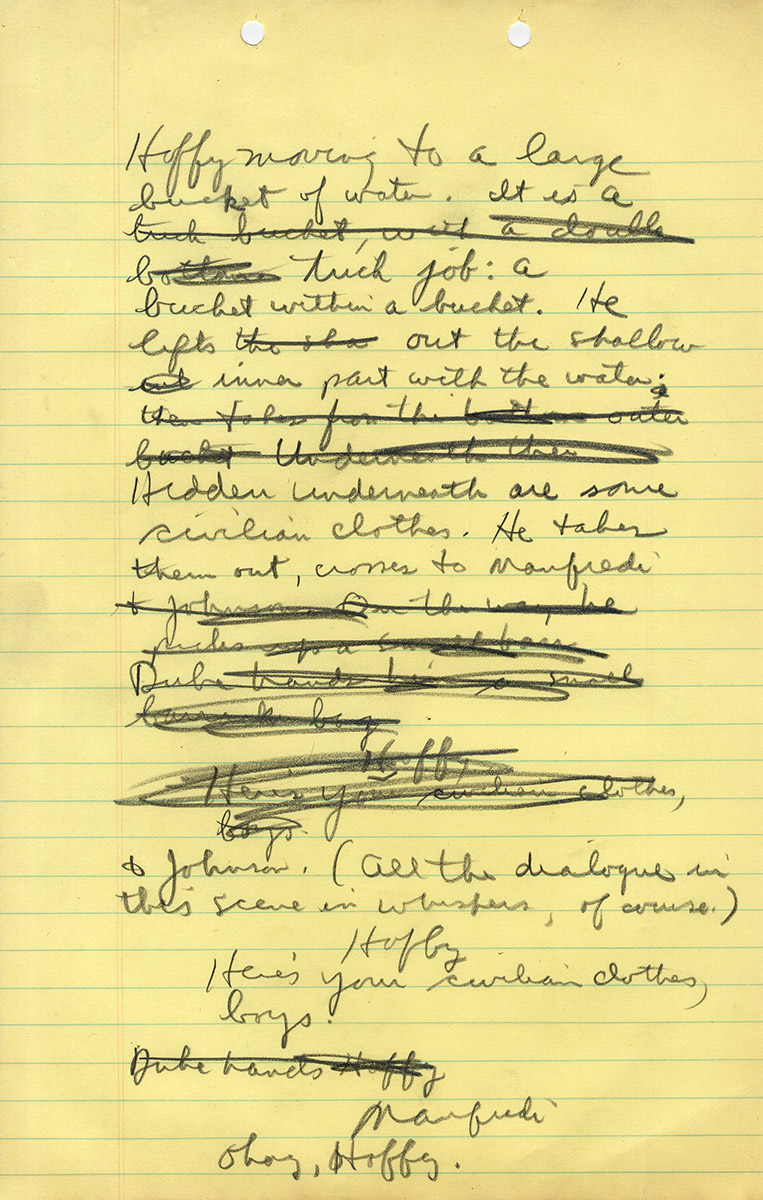

Though handwritten, this is not a treatment, but very close to a shooting script, including dialogue and the occasional indication of a camera angle. To create a workable shooting script from this draft, all a secretary would need to do would be to type it up and add shot numbers. It is, in fact, remarkably close to the “Final White” screenplay. Like the “Final White” version, it is broken down into sequences, “Sequence A”, for example, consisting of our introduction to the setting and the characters and the failed escape attempt of Manfredi and Johnson. Readers interested in Wilder’s creative process can see how certain lines are crossed out and rewritten, for example, “He’d bet on his mother having a stroke” is rewritten as “He’d make a book on his own mother getting hit by a truck!”

Impressively, for an immigrant artist born and raised in Austria, Wilder writes English fluently, with no noticeable errors in grammar or spelling, and a sure grasp of American idiom.

As noted, this handwritten draft, aside from some tweaking of the dialogue and narration, is not that much different from the “Final White” screenplay, and the “Final White” is very close to the completed film. One interesting difference is the omission of an oblique reference to the Holocaust which appears in the typed portion of the handwritten draft. It has Schulz, one of the guards, saying to the prisoners, “I wish I could invite you to my house for a nice German Christmas” — a line that remains in the film — and the prisoner Harry, who is Jewish, saying, “Why don’t we accept, Animal? The worst that could happen is we end up a couple of lampshades.” In the film, the lampshade line is removed and replaced by Animal barking back, dog-like, at the German guard’s “Raus! Raus!”

The handwritten draft is not a complete screenplay. While it tracks very closely the “Final White” screenplay, scene by scene and line by line, it stops abruptly after the entrance of the downed flier, Lieutenant Dunbar (Don Taylor), whom Sefton will eventually help to escape. In other words, it stops exactly at a point equivalent to page 63 of the “Final White” screenplay, and 54 and ½ minutes into the completed film.

Regardless, this is a fascinating document. For one thing, there is significantly more description than dialogue, all of it quite clear and functional, none of it superfluous, showing that Wilder was essentially a visual director, notwithstanding his reputation for clever repartee. The STALAG 17 screenplay, as much as anything that Wilder has written, shows his unique ability to employ broad comedy in the midst of a grimly serious situation.

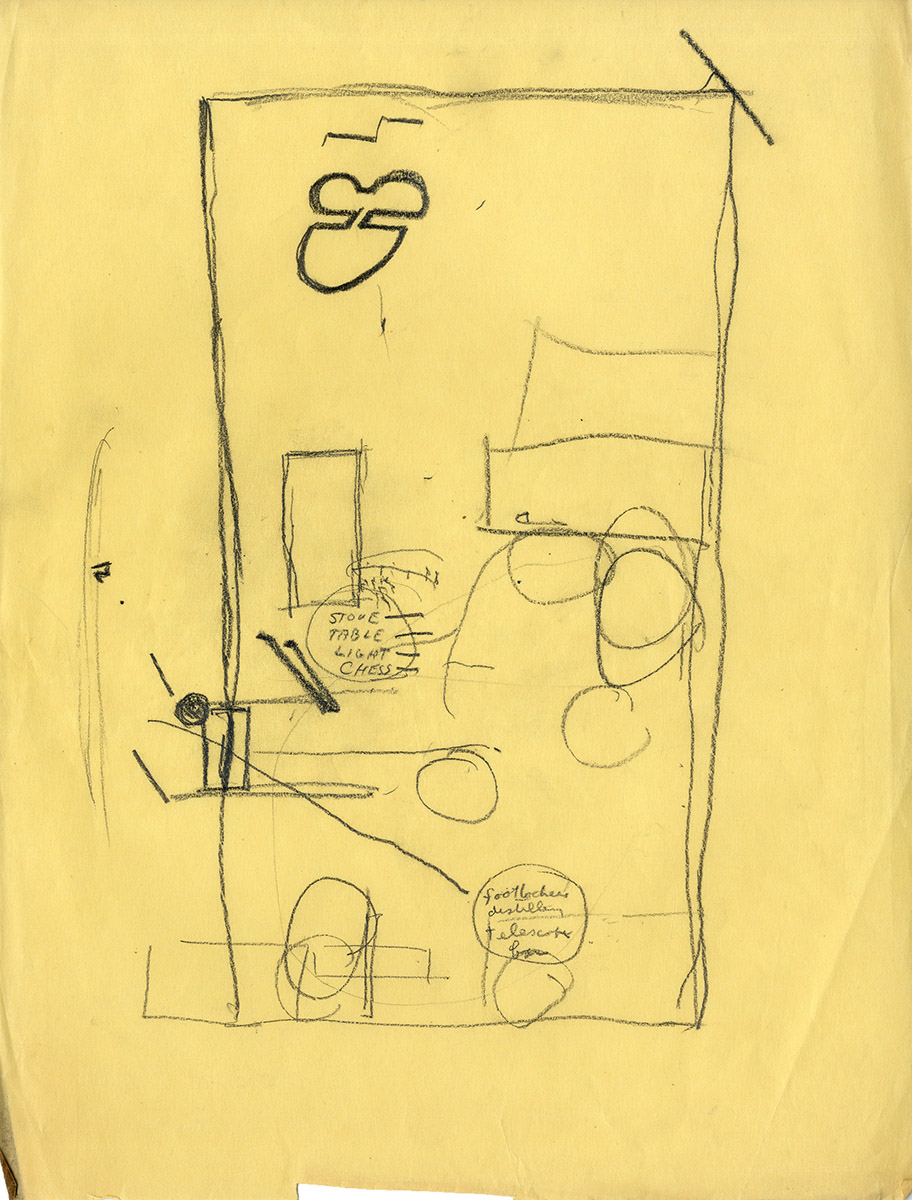

SET ILLUSTRATIONS

There are three simple set illustrations sketched clearly in pencil on yellow paper, probably by Wilder himself:

—Sketch 1: An exterior view of the barracks where our characters are housed. It shows four windows, two doors and a few steps leading up from the ground to each door.

—Sketch 2: An overhead view of the interior of the barracks where most of the action takes place. It shows the locations of the stove covering the escape trapdoor, and the chessboard with the lightbulb hanging above it that the informant uses to communicate information to the guards. In another corner of the barracks next to a window, the sketch indicates the position of Sefton’s distillery and the telescope that allows the occupants of the barracks to spy on the Russian women prisoners.

—Sketch 3: An overhead view, like the interior of the barracks, but not clear exactly what is being shown. Written annotations indicate, “Coffee. Candy. Toothbrushes. Hygienic paper.”

Out of stock

Related products

-

LOOT (ca. Sep 1969) Final Draft screenplay

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

LESBIANS AND BISEXUAL WOMEN IN FILM, THEATER & MUSIC (1901-2004) Archive

$40,000.00 Add to cart -

John Singleton (writer, director) HIGHER LEARNING (Jan 26, 1994) Rainbow film script

$500.00 Add to cart -

CROSS CREEK (Feb 9, 1982) Rev Final Shooting script by Dalene Young

$750.00 Add to cart