BONE [under working title UNREAL] (1972) Shooting script signed by writer-director Larry Cohen

(African American film) Larry Cohen (writer, director) [Los Angeles, 1972]. Vintage original film script, 11 x 8 1/2″ (28 x 22 cm.), printed wrappers, 119 leaves. Signed twice by Larry Cohen, on front wrapper and title page. With numerous MS annotations in Cohen’s hand scattered through the script.

It is often true that a writer/director’s first feature is his most ambitious (see, for example, Orson Welles and CITIZEN KANE). Such is the case with Larry Cohen’s 1972 directorial debut, BONE, a self-produced independent movie that combines elements of black comedy, art film, satire, and theater of the absurd.

Prior to writing and directing BONE, Larry Cohen (1936-2019) had been a prolific television and motion picture writer, working on everything from KRAFT TELEVISION THEATER to THE DEFENDERS, and was responsible for the creation of two successful TV series, BRANDED (1965-1966) and THE INVADERS (1967-1968). He would later make a name for himself as a director of horror (IT’S ALIVE, GOD TOLD ME TO) and blaxploitation films (BLACK CAESAR, HELL UP IN HARLEM). BONE foreshadows elements of both genres.

In fact, the eclectic nature of BONE made it an extremely difficult film to market. Its onscreen title was BONE, A BAD DAY IN BEVERLY HILLS (suggesting the movie’s essentially comedic nature), but distributors tried selling it under titles as varied and misleading as HOUSEWIFE (attempting to market it as a sex film) and its British title, DIAL RAT FOR TERROR (attempting to sell it as a horror film). It’s essentially a home invasion story — a black man coming from nowhere, disturbs the lives of an affluent Beverly Hills couple — but there are also elements of surrealism and fantasy. Hence, the screenplay’s original title, UNREAL.

Clearly, the principal themes addressed by the movie are race and class, while also commenting on issues of consumer capitalism and sex. The four main characters are the white couple, Lenneck (Andrew Duggan) and his wife, Bernadette (Joyce Van Patten), Bone, the black intruder (Yaphet Kotto), and the girl Lenneck meets at a bank, referred to in the screenplay simply as “She” (Jeannie Berlin). As filmmaker Cohen points out in an audio commentary, each of the characters is in some way a fantasy of the others. For Lenneck and Bernadette, Bone embodies their fantasy of the stereotypical black intruder/rapist — hence, one of the screenplay’s key lines:

BONE

I’m just a big black buck doing what’s expected of him.

For Bone, Bernadette embodies his fantasy of the horny white housewife. For Lenneck, “She” embodies his fantasy of having sex with a younger woman. For “She,” Lenneck embodies her fantasy of having sex with the older man who molested her when she was an 11-year-old in a Loew’s movie theater balcony.

The screenplay begins with the following image which plays under the movie’s title credits:

CLOSE UP

A bare light bulb dangling by a frayed cord. It burns brightly — insistently — blindingly —

As we learn later, the bulb hangs in a jail cell occupied by the white couple’s 18-year-old son — they tell everyone he’s a helicopter pilot in Vietnam, but he is actually incarcerated in a Spanish prison for selling hashish. The fact that the screenplay begins with the bare bulb and ends with the son smashing it suggests that the entire story might be his fantasy of his parents’ destruction.

The sequence that immediately follows the opening shot shows Lenneck — he owns a car dealership — standing in an automobile graveyard making a sales pitch to the camera:

LENNECK

(to us)

Hi friends. It’s me again, Bill. Bill Lenneck. Lenneck’s Auto Circus right out here where the friendly freeways meet.

Per the screenplay, the camera pulls back to show piles of wrecked cars, “some five stories high”, and inside the wrecked cars, the bloodied corpses of accident victims. This imagery, reminiscent of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1968 film WEEKEND, immediately sets us up for the mixture of satire, nightmare, and surrealism that is to follow.

Bone, searching the white couple’s house for money, discovers that they are, in fact, deeply in debt, although the husband has a secret bank account in which he has stashed $5,000. Bone threatens to rape the wife and slice her throat with a gold letter opener afterwards, if Lenneck does not go to the bank and return with the $5,000 within the hour. (It is significant that Bone carries no weapons himself other than his “blackness.”) While at the bank, Lenneck runs into “She” and digresses to have an affair with her, rather than returning home with the money, not at all disturbed by the likelihood that Bone will kill Bernadette during his absence. In the meantime, Bone and Bernadette become allies and plot to murder Lenneck, DOUBLE INDEMNITY-style. Most of the screenplay intercuts between scenes of the two couples — Bone and Bernadette; Lenneck and the eccentric grafter, “She”.

This particular copy of the screenplay was Cohen’s personal shooting script — the completed film follows the screenplay closely — and it is heavily annotated in pencil and ink by the writer/director. The annotations consist of notes on camera placement (“360′ camera turn around phone”), indications of business, lines underlined for emphasis, and additional dialogue. For example, when Bone and Bernadette find Lenneck’s life insurance policy, Bernadette comments, “From here on WE’RE IN GOOD HANDS,” to which Cohen has added in pencil, “I know all about them good hands.”

BONE is a prime example of 1970s New American Cinema. Cohen’s screenplay ends with Bernadette beating her husband to death on a sand dune, with no physical help from bystander Bone. And then Bone disappears as magically as he appeared in the first place — suggesting he never existed at all.

Out of stock

Related products

-

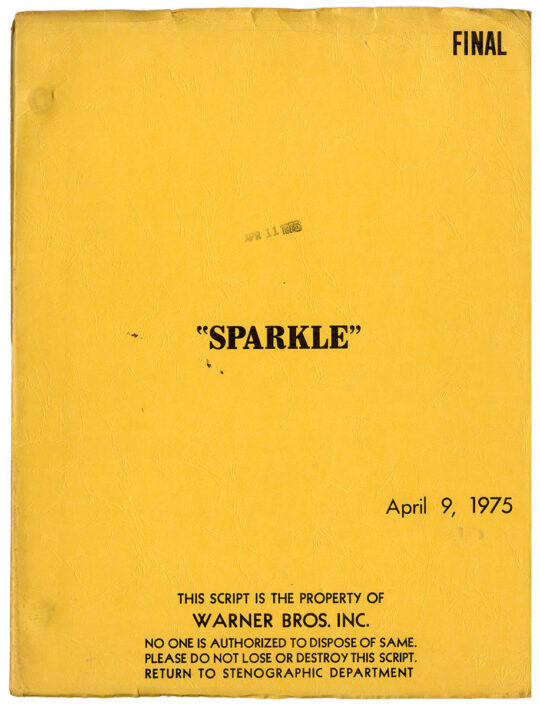

(Blaxploitation film) SPARKLE (Apr 9, 1975) Final Draft film script by Joel Schumacher

$750.00 Add to cart -

LOOT (ca. Sep 1969) Final Draft screenplay

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

![CHINATOWN [ca. 1973] Jack Nicholson's copy of early draft film script by Robert Towne](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/ChinatownSCR_a-540x693.jpg)

CHINATOWN [ca. 1973] Jack Nicholson’s copy of early draft film script by Robert Towne

$18,500.00 Add to cart -

![MON ONCLE D'AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French screenplay](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/MonOncleDAmeriqueFR-SCR_a-540x745.jpg)

Alain Resnais (director) MON ONCLE D’AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French film script

$2,500.00 Add to cart

![BONE [under working title UNREAL] (1972) Shooting script signed by writer/director Larry Cohen](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/BoneSCR_a.jpg)

![BONE [under working title UNREAL] (1972) Shooting script signed by writer-director Larry Cohen - Image 2](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/BoneSCR_b.jpg)

![BONE [under working title UNREAL] (1972) Shooting script signed by writer-director Larry Cohen - Image 3](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/BoneSCR_c.jpg)

![BONE [under working title UNREAL] (1972) Shooting script signed by writer-director Larry Cohen - Image 4](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/BoneSCR_d.jpg)