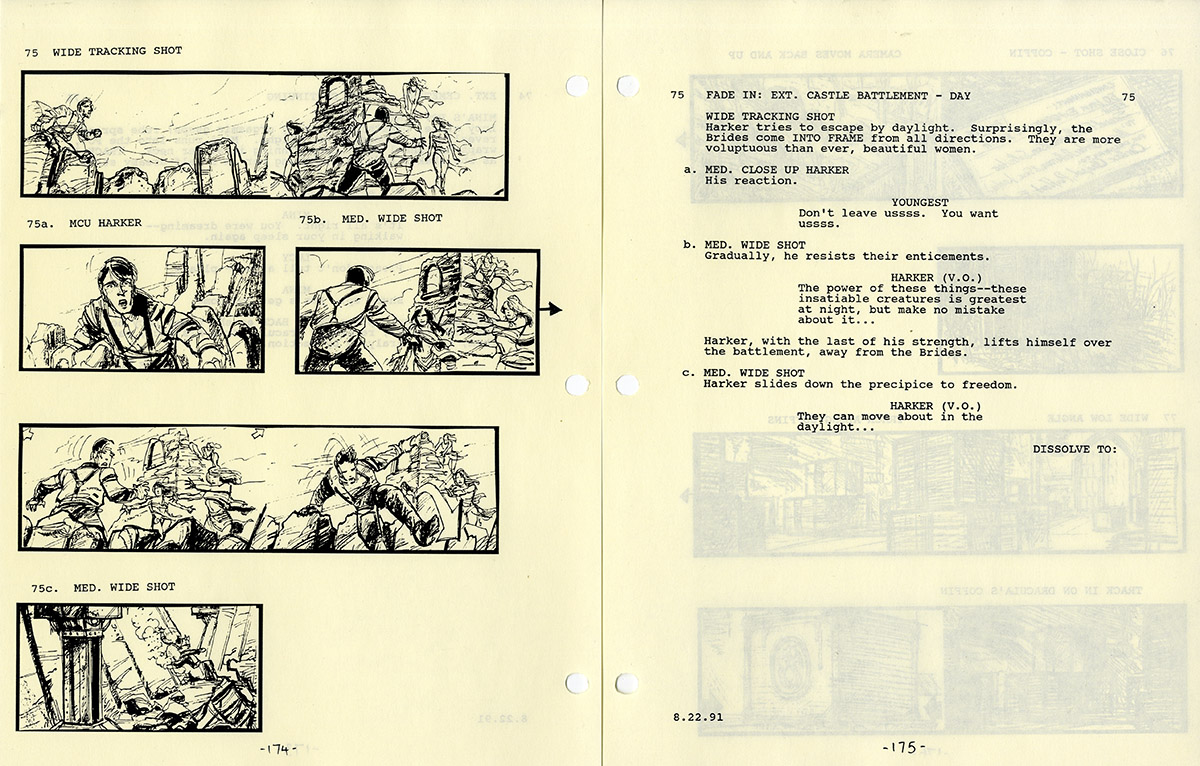

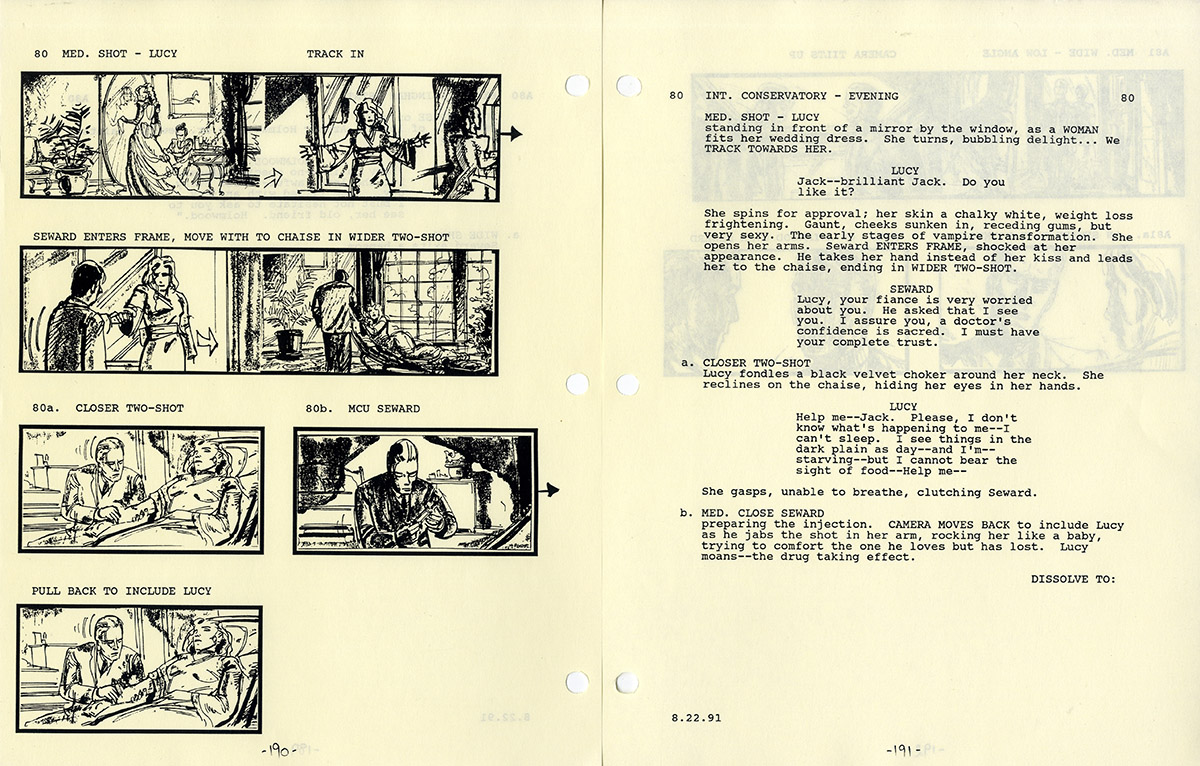

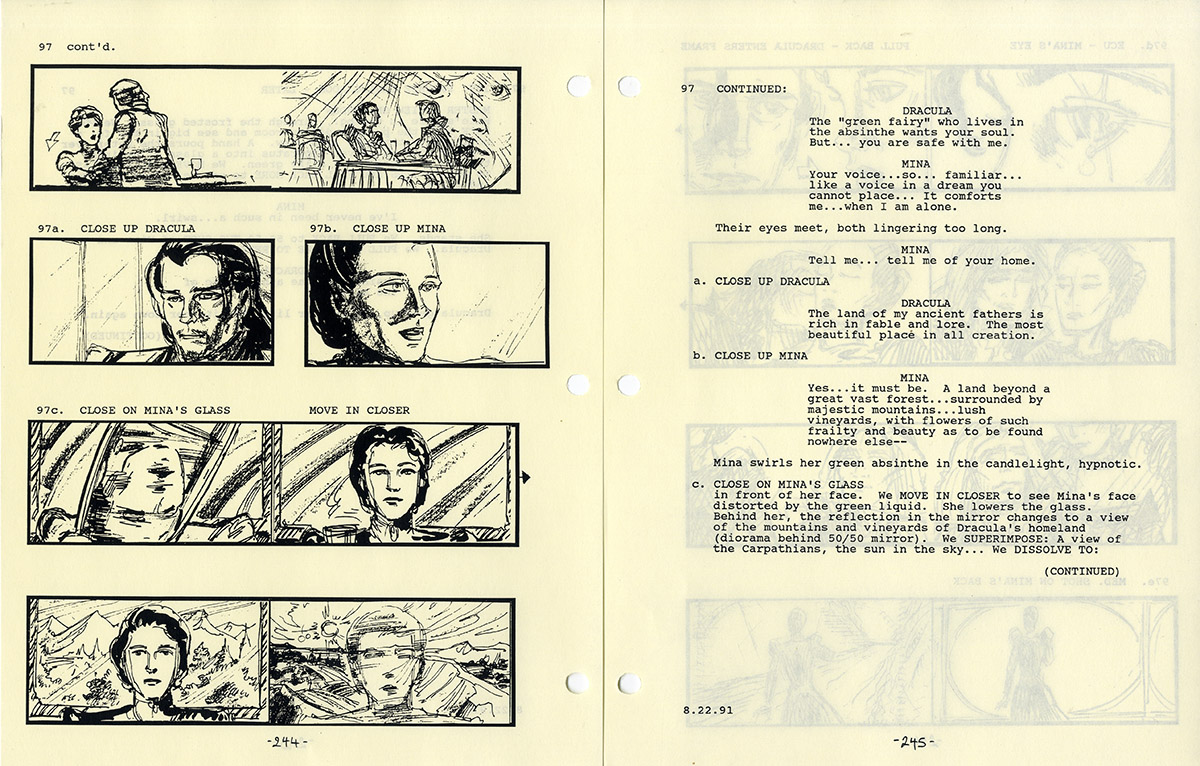

Bram Stoker’s DRACULA (1991-92) Revised film script with storyboards

San Francisco: American Zoetrope, 1991-1992. Vintage original film script, quarto, bound in a binder with three holes punched, 437 page script,1991, with storyboards bound behind each page of script in three hole punched binder, and with 12 pages of revisions (storyboards on versos) dated 11-18-91 laid-in. Also a 33 pp.SCENES REMAINING TO BE SHOT, dated 1-7-92. Near fine or better.

A massive script, with an utterly complete set of storyboards printed on the verso of each page, for Coppola’s visually compelling treatment of the story of Dracula.

According to director Francis Ford Coppola, James V. Hart’s DRACULA screenplay had already been written before he agreed to direct it. The screenplay was brought to Coppola by actress Winona Ryder while Coppola was completing GODFATHER III. Ryder was originally supposed to star in GODFATHER III, but had to drop out for health reasons, and she offered the DRACULA screenplay to Coppola as a way of making amends. As it happened, Coppola had always loved Bram Stoker’s novel and the movies made from it, so he was more than willing to tackle the project.

James V. Hart was a Texas-born novelist who had previously written the screenplay for Stephen Spielberg’s HOOK. His subsequent screenplays included BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA, MARY SHELLEY’S FRANKENSTEIN (produced by Coppola, but directed by Kenneth Branagh), and the Robert Zemeckis sci-fi epic, CONTACT.

Just as Coppola insisted on titling his Godfather films, MARIO PUZO’S THE GODFATHER, he decided to call his Dracula movie BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA out of respect for the source material. Though in many ways the movie is extraordinarily faithful to the novel, in some ways the most faithful film adaptation of Stoker’s book, Hart and Coppola added elements, including a prologue based on the real-life history of Vlad Tepes aka Vlad the Impaler, the Romanian warrior king who inspired Stoker’s vampire, and they also chose to elaborate the romantic/erotic aspects of the story, i.e., the relationship of Dracula and Mina who, in the Hart/Coppola retelling, is presented as the reincarnated version of Vlad’s original great love. (The reincarnation concept derives not from Stoker’s novel, but from the 1932 Universal film, THE MUMMY, directed by Karl Freund who had photographed the Tod Browning/Bela Lugosi DRACULA one year earlier.)

Due in part to the complexity of the special effects, almost all of which were done in-camera (the same way filmmakers created special effects in the 1920-30s), BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA was perhaps the most meticulously pre-planned of all of Coppola’s movies; and this pre-planning is reflected in the 437-page screenplay which includes printed storyboard illustrations of every shot in the film, facing the pages containing the scene descriptions and dialogue.

Notwithstanding the shot-by-shot pre-planning that we see in this illustrated screenplay, there are a number of noteworthy differences between the script and the completed film. For example, Winona Ryder’s part was built up in the prologue, so that the film has a shot of her 15th Century alter ego getting married (with Gary Oldman as Prince Vlad, and Anthony Hopkins, who also plays Dr. Van Helsing, as the Priest who marries them), and the movie adds a shot of her character in puppet form leaping from a tower to her doom after she hears the falsely reported news that her Prince is dead.

There is also some significant reordering of scenes. For example, in the screenplay the first scene taking place in the London present is that of Mina (Ryder) and her best friend Lucy (Sadie Frost) in a parlor discussing their respective boyfriends, whereas the film’s first scene after the prologue is mad Renfield (Tom Waits) in the insane asylum of Dr. Seward (Richard E. Grant). The movie has more Coppola-style cross-cutting than the screenplay, and some of the screenplay’s visual ideas were omitted from the film, for example, during the scene where Jonathan Harker (Keanu Reeves) is being seduced by Dracula’s vampire brides, a shot of the shadow of a woman “being decapitated on the silks, repeated over and over.” A sequence in which Jonathan is stalked outside by the three vampire brides during daylight is omitted. A scene in which Dracula and Mina make love in a coach prior to her marriage to Jonathan is also omitted from the film.

Shadows that move independently from the characters who cast them are a recurring visual motif. Anti-gravity and superimposition effects abound. Coppola self-consciously references the expressionistic horror of F.W. Murnau (NOSFERATU) and Carl Dreyer (VAMPYR) along with the surrealist poetry of Jean Cocteau (BEAUTY AND THE BEAST). The film’s references to the early days of cinema even include a visit by Mina and Dracula to a turn-of-the-century kinematograph (an early form of movie theater). The scene at the kinematograph is expanded in the movie to include interaction between Mina, Dracula, and a wild wolf loose in the theater – the beast likes her.

This is a film in which the costume designer, Eiko Ishioka, can be credited as one of its principal auteurs. (She received an Academy Award for her contribution). Screenwriter James V. Hart should be commended for creating the most complex of screen Draculas, a character who is noble and tragic as well as a monster.

Can Coppola be considered a true horror director? In light of his work on Roger Corman’s THE TERROR, DEMENTIA 13, DRACULA, and, more recently, 2011’s TWIXT, the answer is a definite yes. The horror genre frees a director like Coppola to be more experimental and romantically expressionistic than would be popularly acceptable in more “serious,” less dream-like genres.

BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA is one of Coppola’s finest and most underrated achievements. The director has often spoken of his admiration for British filmmaker Michael Powell, in particular his 1940 THIEF OF BAGDAD and 1951 THE TALES OF HOFFMANN. The combination of magic, eroticism, and visual lushness in BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA makes it the most Powell-like of Coppola’s features.

Revised Scenes – November 4, 1991. 8 pp. (light yellow)

- A slightly revised version of the scene with Quincey, Van Helsing, and Lucy lying in bed after she has been vampirised.

- A slightly revised version of the scene with Jonathan, Mina, and Van Helsing at supper as Van Helsing describes how he cut off Lucy’s head and drove a stake through her heart.

Revised Scenes – November 18, 1991. 12 pp. (orange) including storyboard illustrations facing dialogue and description

- A revised version of the scene where Dracula consummates his love with Mina by having her drink is blood. In this version, he hesitates before letting her drink, but she encourages him.

- A scene where Van Helsing trepinates (drills a hole in) Renfield’s head – not in the movie.

- A slightly revised version of the scene where Jonathan and Van Helsing confront Dracula as he is vampirising Mina.

SCENES REMAINING TO BE SHOT – January 7, 1992. 33 pp. plus title page (white, bound)

- Slightly revised version of the Prologue, Dracula’s victory over the Turks, Elizabeth’s suicide.

- Shots pertaining to Jonathan’s visit to Castle Dracula and his interactions with the Count. His seduction by the Brides.

- Dracula’s journey to London by sea. A wolf escapes from London zoo.

- Shots and inserts remaining to be photographed involving Lucy and Mina in London, and the final pursuit of Dracula by Van Helsing et al. as the vampire returns to his Romanian homeland, now including Van Helsing’s final movie line, “We have all become God’s madmen.”

Out of stock

Related products

-

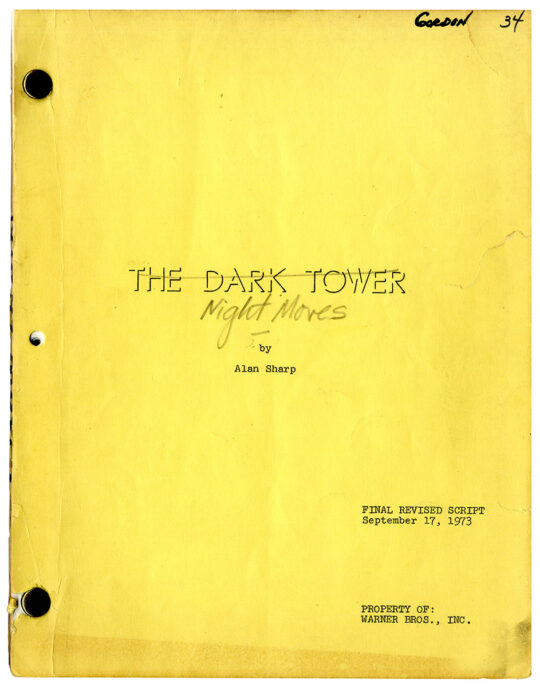

Arthur Penn (director) NIGHT MOVES [working title: THE DARK TOWER] (Sep 17, 1973) Final revised film script

$2,000.00 Add to cart -

LONG WALK HOME, THE (Oct 13, 1988) Second draft film script by John Cork

$375.00 Add to cart -

(Blaxploitation film) SPARKLE (Apr 9, 1975) Final Draft film script by Joel Schumacher

$750.00 Add to cart -

![ESCAPADE [working title for: A WARM DECEMBER] (Jun 11, 1971) Revised First Draft screenplay](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/EscapadeSCR_a-540x695.jpg)

ESCAPADE [working title for: A WARM DECEMBER] (Jun 11, 1971) Revised First Draft screenplay

$500.00 Add to cart