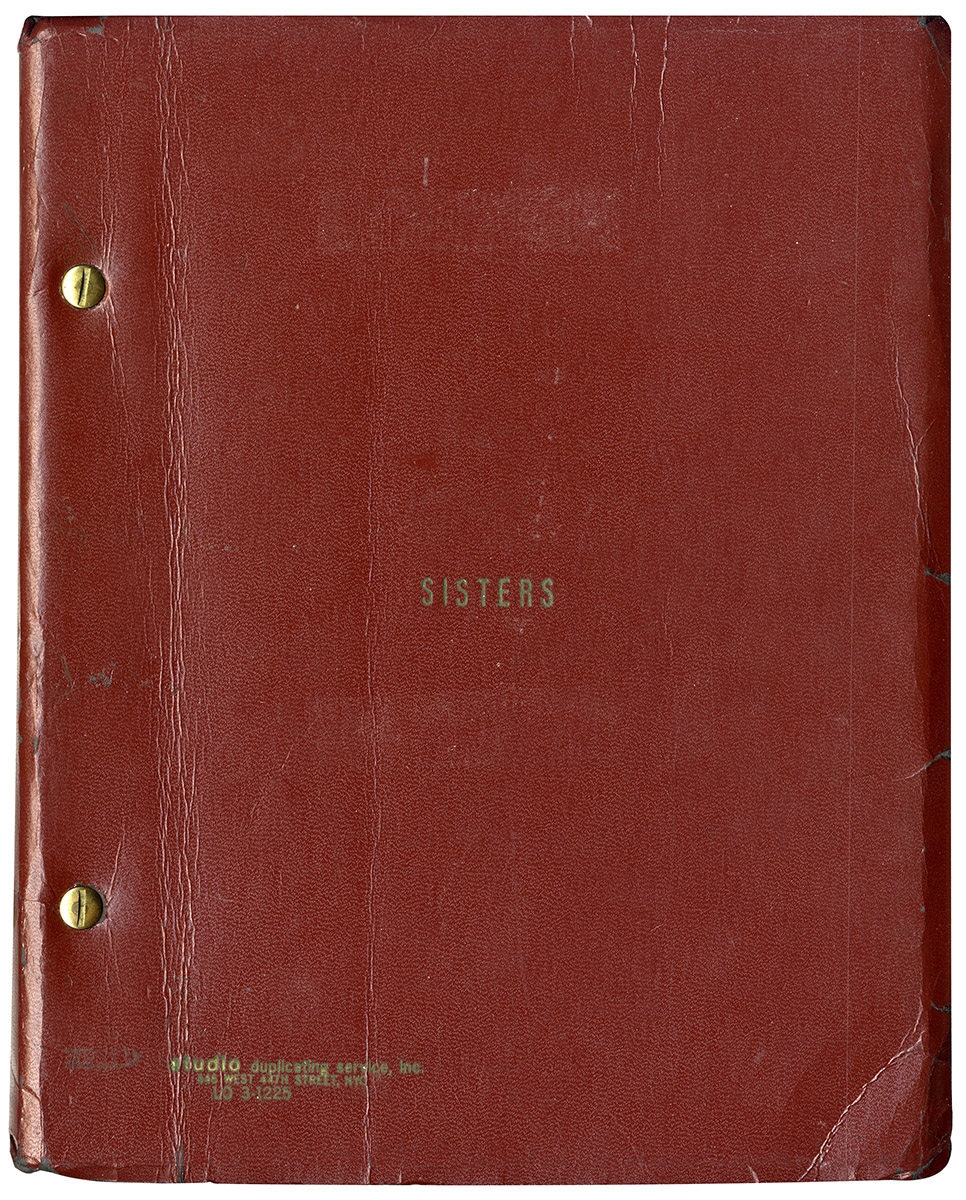

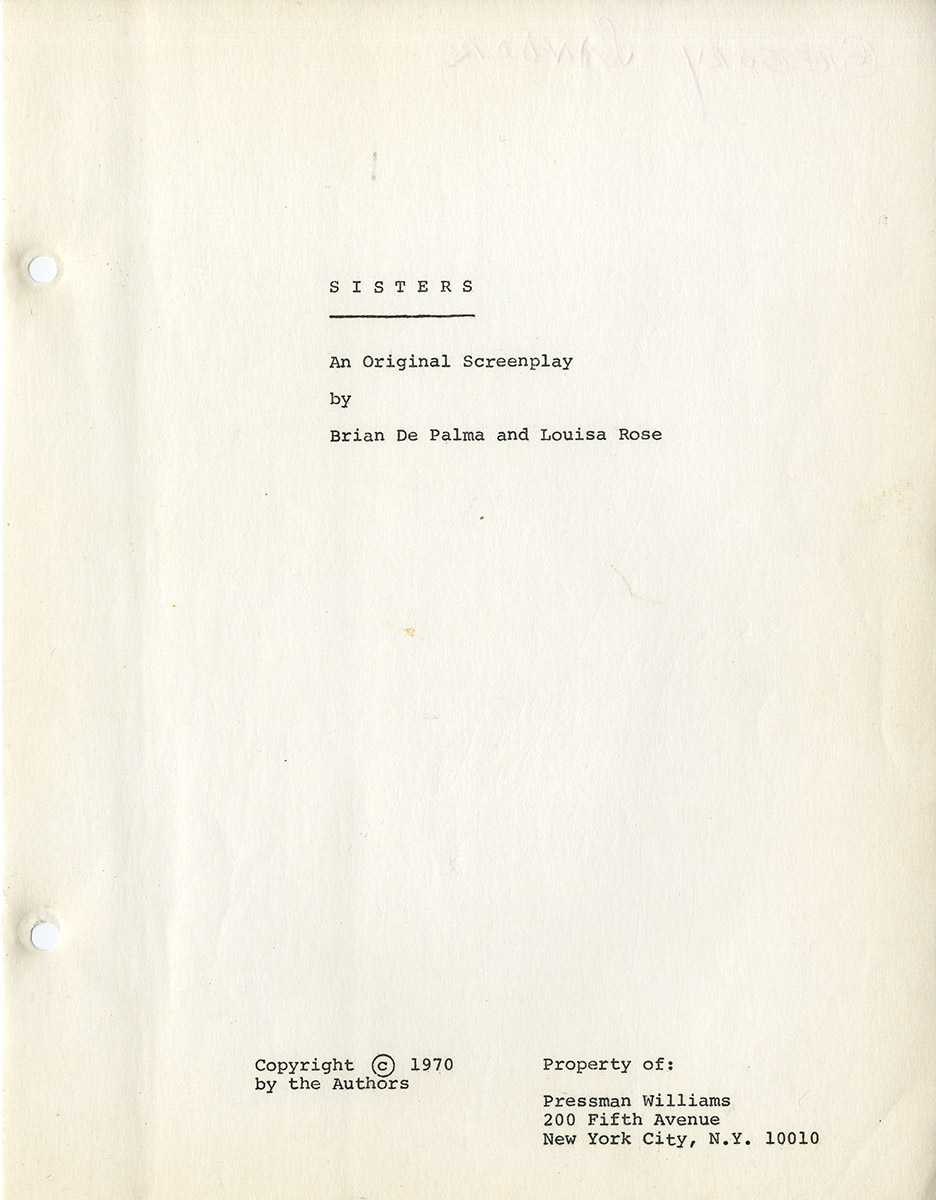

Brian De Palma (director, screenwriter) SISTERS (1970) Film script

New York: Pressman-Williams, 1970. Vintage original film script. Maroon titled wrappers. 138 leaves, with last page of text numbered 138. Near fine in very good+ wrappers, brad-bound. Copy belonging to cinematographer Gregory Sandor, with his name in holograph pencil on the verso of the title page, and holograph pencil annotations throughout. Missing page 83, likely as used or issued.

Sisters (1973) was the seventh feature film directed by Brian De Palma (born Newark, New Jersey, September 11, 1940) and his first major commercial success. After five independent features, including the cult classic Greetings (1968), and one prior Hollywood film, the little-seen Get to Know Your Rabbit (1972), Sisters was the first Hollywood film directed by De Palma in the Hitchcockian mode that would establish him as the “New Modern Master of the Macabre.” This is one De Palma script which turns up seldom and is definitely very scarce.

Sisters borrows the plot structure of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), but with a feminist twist. Just as Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) in Psycho has an alternate personality, that of his deceased mother Mrs. Bates, who murders people, Danielle (Margot Kidder) in Sisters has an alternate personality, that of her deceased Siamese twin sister Dominique, who is a murderess. However, if Danielle/Dominique is a monster, De Palma’s film squarely blames the creation of that monster on the patriarchal society that oppressed her “freakishness,” in particular, Danielle’s psychiatrist ex-husband, Emile Breton (William Finley), who killed Dominique when he surgically separated her from Danielle to fully possess the surviving twin.

Sisters also pointedly evokes Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954), again adding a feminist twist, with its other protagonist, the journalist Grace Collier (Jennifer Salt) who, like James Stewart in Rear Window, witnesses a murder through the window of the apartment facing hers, specifically, the murder of a young black man (Lisle Wilson) by Danielle/Dominique, and, of course, no one in the male establishment believes her. Film critic and scholar Robin Wood, who called Sisters “De Palma’s finest achievement prior to Blow Out and one of the great American films of the 70s,” observed that Sisters “analyzes the ways in which women are oppressed within patriarchal society on two levels, the professional (Grace) and the psychosexual (Danielle/Dominique).”

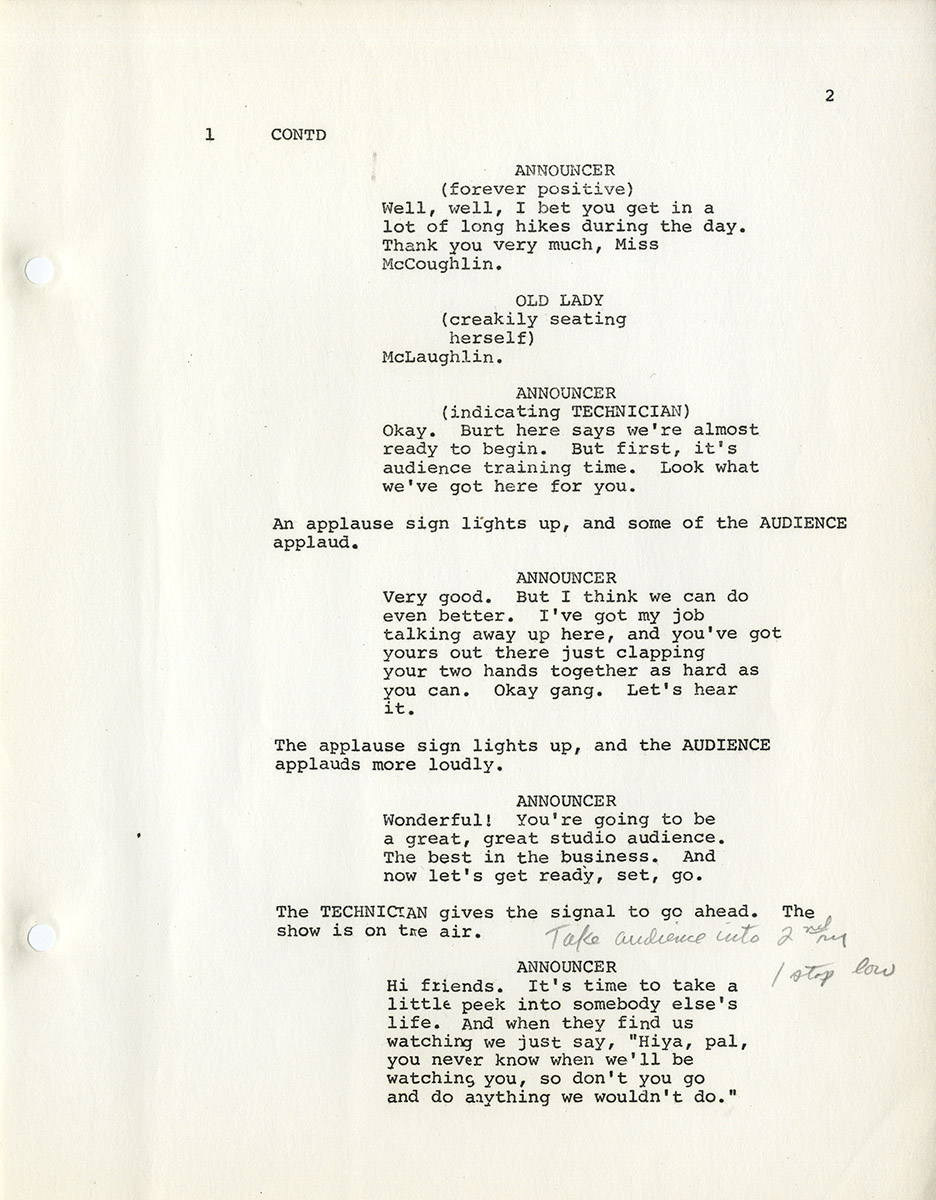

The 1973 film version of Sisters, while preserving the characters and structure of the 1970 screenplay, is a considerably more polished and developed version of that screenplay. Unlike the screenplay, the film begins with a gripping title sequence, demanded by the film’s composer, Bernard Herrmann (who also composed the score of Psycho). The 1970 script begins with an elaborate sequence, shot inside a TV studio, of a comic announcer “warming up the audience for a live broadcast of Peeping Toms, a local version of Candid Camera.”

The film, on the other hand, begins (following the Herrmann title sequence) with a sustained suspenseful shot of a pretty, apparently blind, young woman (Kidder) starting to undress in a changing room, in the presence of a young black man (Wilson) of whom she seems to be unaware. Only then does the frame freeze, and we hear the voice of an announcer indicating that we are watching a Candid Camera-type TV show. (In short, the script begins with comedy, while the film begins with suspense.)

In the movie, the girl pretending to blind is named Danielle Breton and she is French-Canadian. In the script, her name is Ava Kirst and she is Swedish. In the script, after the game show, the girl and Phillip, the black man, dine at the “Shoreham Motor Lodge Pancake House.” In the movie, they dine at the “African Room,” a ludicrously jungle-themed restaurant which emphasizes the theme of race. At this point in the film, we meet the girl’s ex-husband, Emile Breton, also French-Canadian, who has been stalking her. In the script, he is named Eric Roamer (like the French filmmaker Eric Rohmer) and he is Norwegian. Subsequent scenes in the script taking place in a skating rink, a coffee shop, a car, and a drive-in are completely omitted from the film. When Phillip goes to Ava’s apartment to make love to her, and hears, but does not see, Ava talking to her twin sister, we learn the sister’s name is Elsa, not Dominique as in the film.

There are many more substantial differences between the script and the film. The script is much talkier, more dependent on dialogue, than the film. In both the script and the film, Grace hires a private detective (Charles Durning) to find Philip’s body which her ex-husband has hidden in a foldaway couch. However, in the script, the detective is murdered by Ava/Elsa (like Detective Arbogast in Psycho). In the movie, there is no attempt on the detective’s life. The last shot described in the script is of the couch with the dead detective’s hand protruding from it. The last shot of the film has the private detective observing the couch from atop a telephone pole. The script takes place in Hartford, Connecticut. The film was shot on location in Staten Island.

One of the most distinctive and highly praised aspects of Sisters, the film, is De Palma’s use of split-screen, and this is laid out in the 1970 script. When Grace witnesses the murder of Phillip from across the way, the script splits into two columns representing the splitting of the screen, the left column describing what the twin is doing, left screen, joined by her ex-husband as they try to clean up after the murder, and the right column describing what Grace is doing as she calls the police and tries to get them to accompany her to the apartment to apprehend the murderess.

Aside from splitting, twins, and doubles, the script and film’s other major motif is looking. The story begins with the PEEPING TOMS show, the audience looking at Phillip looking at the apparently blind Danielle as she is about to undress. The psychiatrist stalks and spies upon his ex-wife. Then we have Grace looking through her window at the murder occurring across the way. There is a hallucination sequence which, per Robin Wood, “is introduced by Emile’s telling [Grace, under the influence of a hypnotic drug] that, as she wanted to see, she will now be forced to witness everything, and is punctuated by huge close-ups of her terrified eye.” Finally, the film ends with the detective looking with his binoculars from atop the telephone pole at the couch containing the murder victim, futilely waiting for the owners of the couch to pick it up.

Out of stock

Related products

-

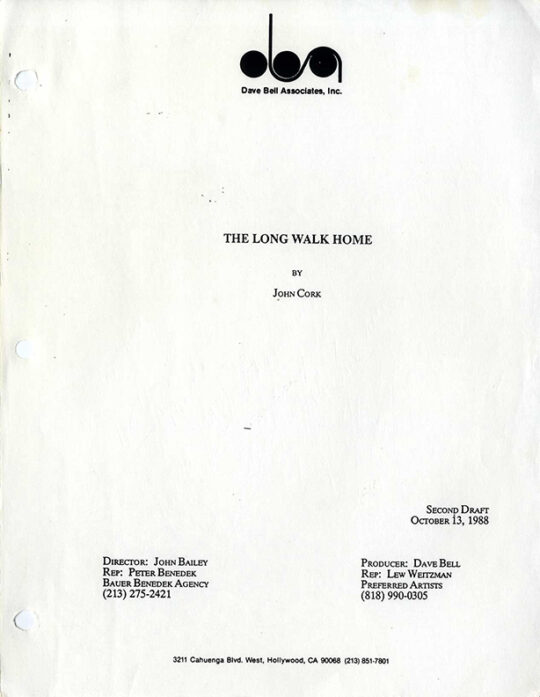

LONG WALK HOME, THE (Oct 13, 1988) Second draft film script by John Cork

$375.00 Add to cart -

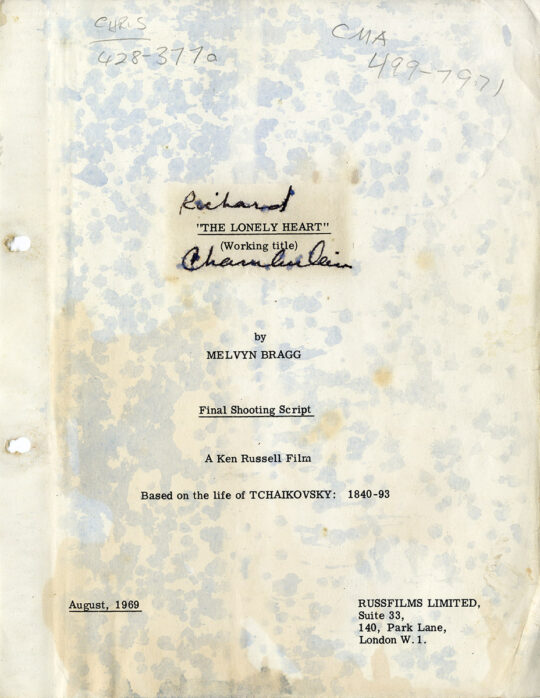

Ken Russell (director) THE MUSIC LOVERS [working title: THE LONELY HEART] (1969) Final shooting script

$3,000.00 Add to cart -

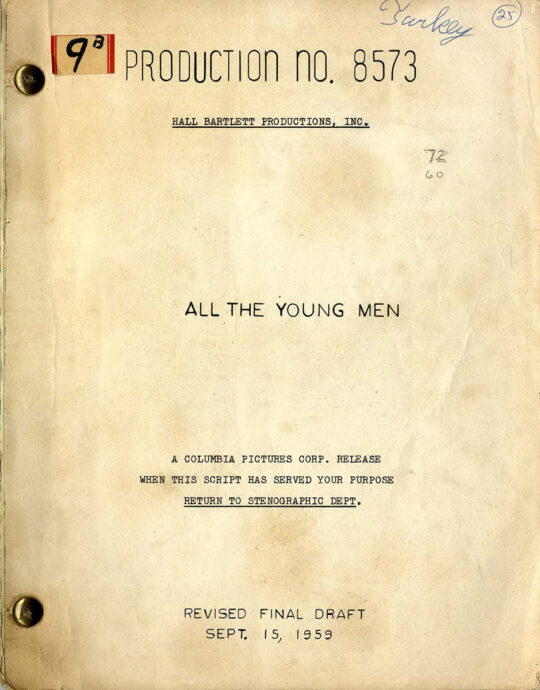

ALL THE YOUNG MEN (Sep 15, 1959) Revised Final Draft script by Hall Bartlett

$450.00 Add to cart -

![MON ONCLE D'AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French screenplay](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/MonOncleDAmeriqueFR-SCR_a-540x745.jpg)

Alain Resnais (director) MON ONCLE D’AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French film script

$2,500.00 Add to cart