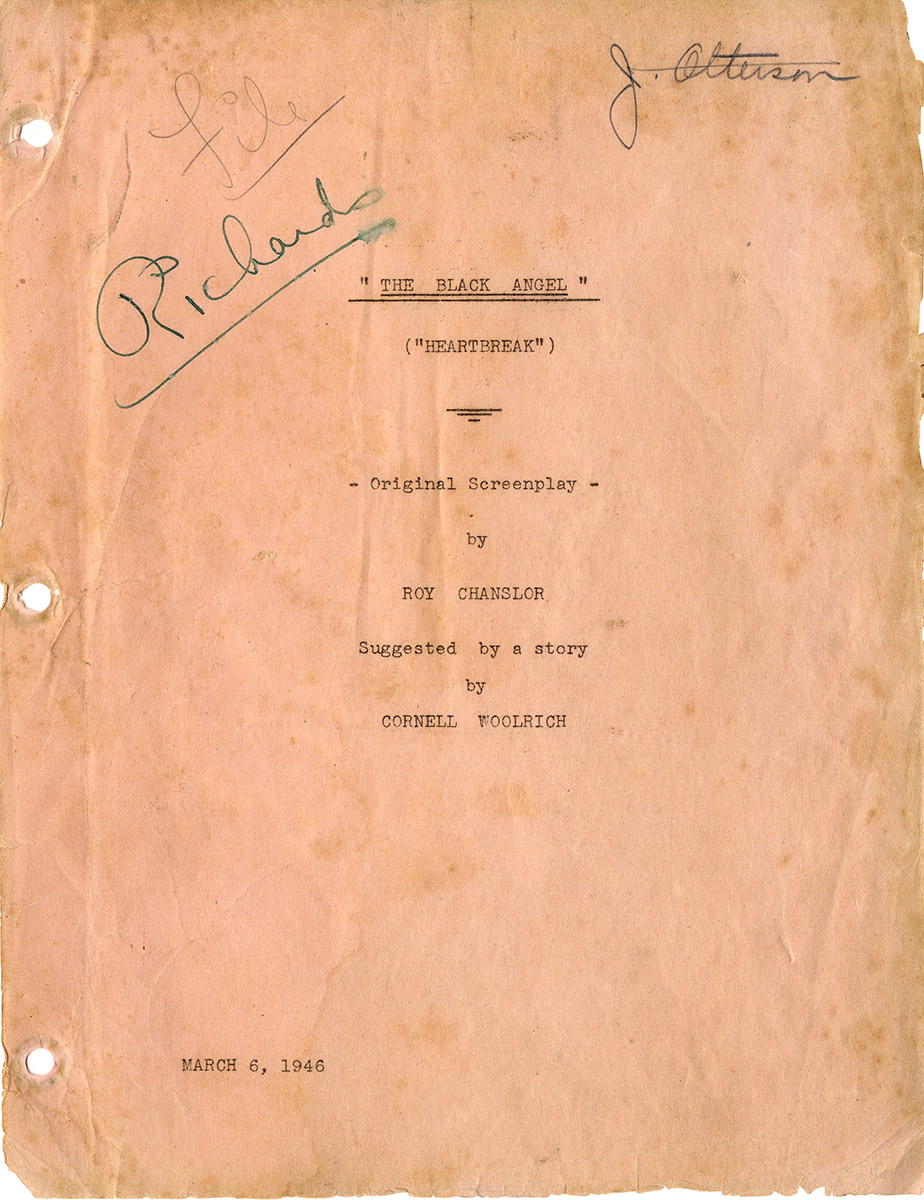

Cornell Woolrich (source) BLACK ANGEL (Mar 6, 1946) Film script

[Los Angeles: Universal Pictures], March 6, 1946. Vintage original film screenplay, 11 x 8 1/2″ (28 x 22 cm.), self-wrappers bound in plain stiff wrappers, mimeograph, on pink paper. There is a tiny bit of staining on the first few pages around the edges. The first interior page has some tiny paper loss down the right edge and has a plastic sleeve to protect it. The final leaf is intact and has also been placed in a plastic sleeve. Very good+.

Cornell Woolrich (1903-1968) was one of the twentieth century’s leading novelists and short story writers in the genre we now call noir, and indisputably one of the most influential figures in film noir. By the time Black Angel was filmed in 1946, more than a half dozen of Woolrich’s works had been adapted to the screen, including The Leopard Man (Jacques Tourneur, 1943) and Phantom Lady (Robert Siodmak, 1944), and there would be dozens more, notably including Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) and François Truffaut’s The Bride Wore Black (1968) and Mississippi Mermaid (1969). The hallmark of a Woolrich noir is a loser protagonist caught in the cruel web of fate.

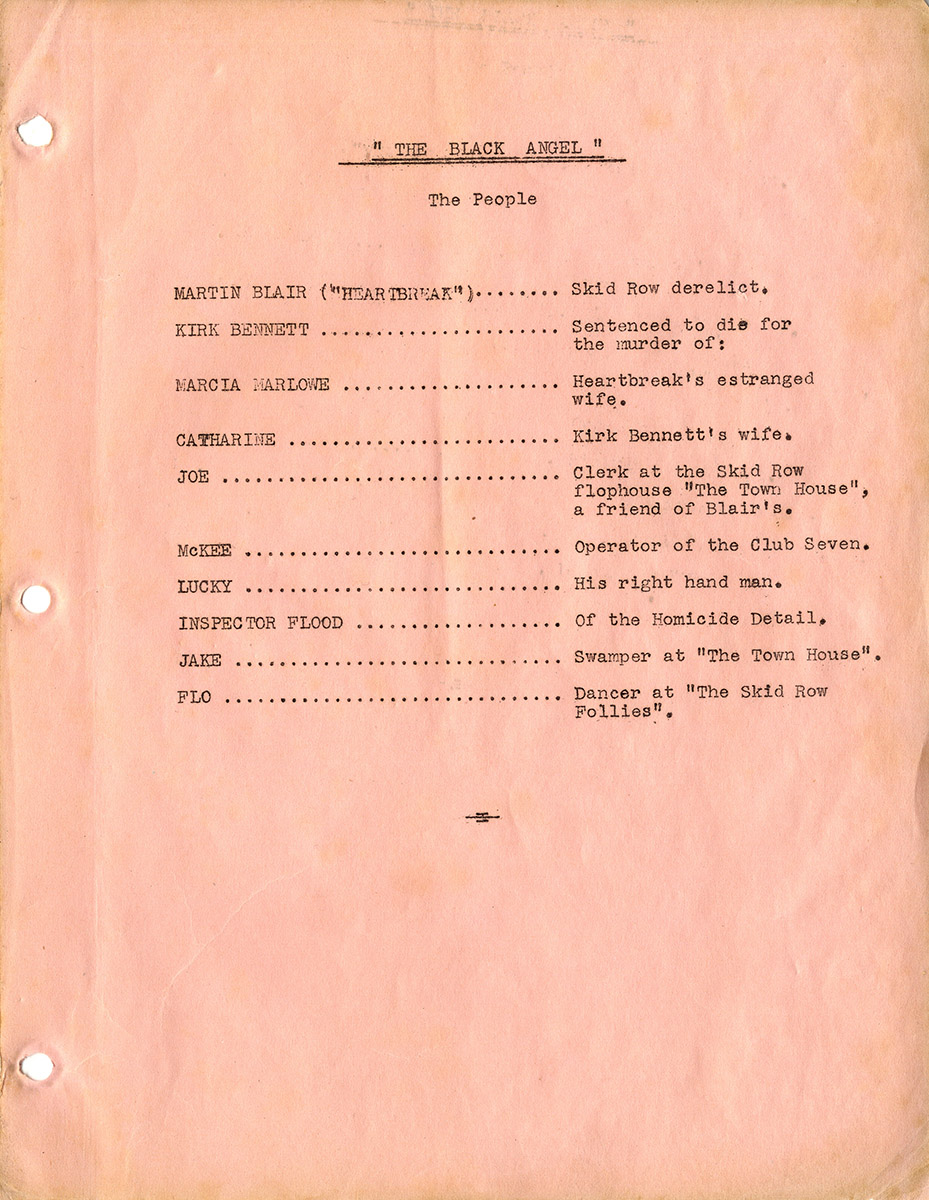

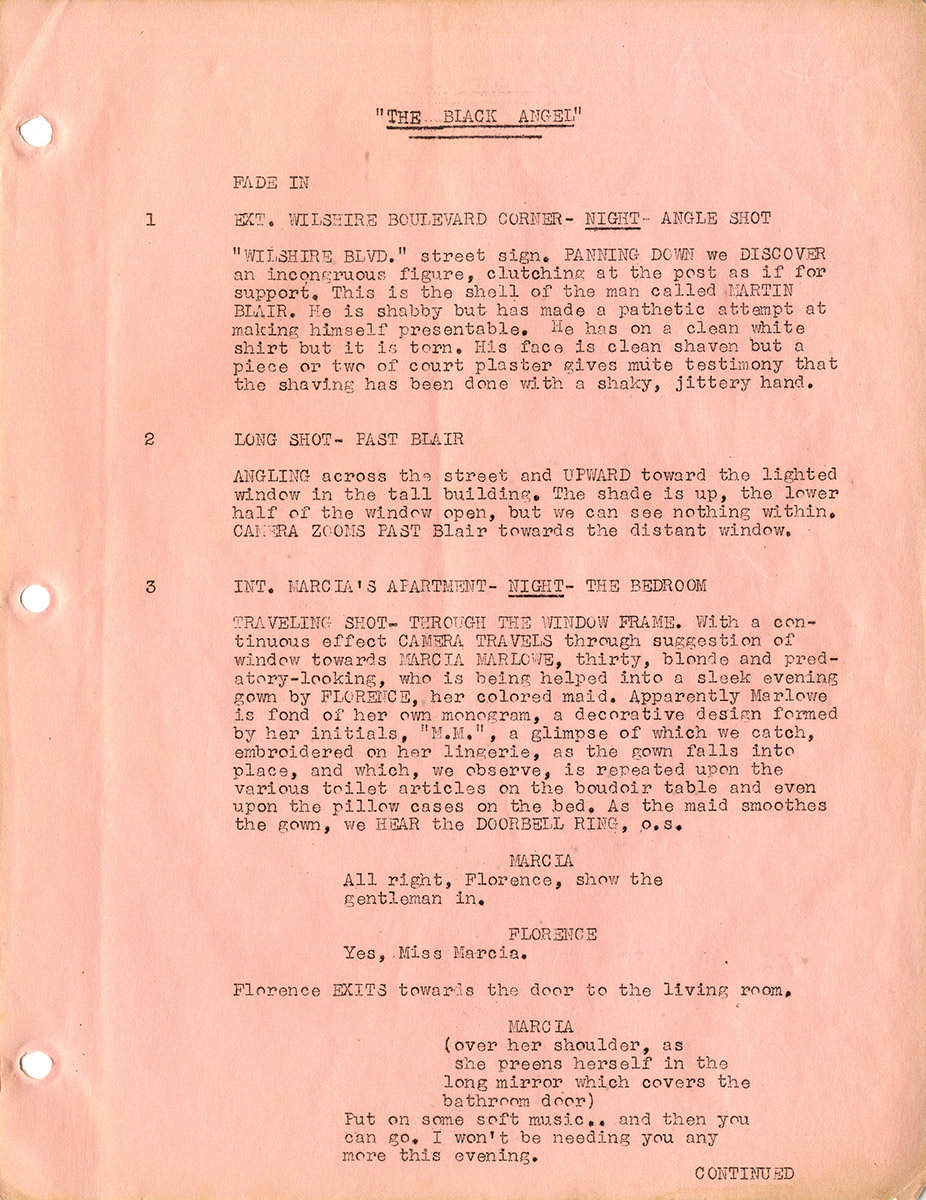

In Black Angel we have two loser protagonists. There is Kirk Bennett (John Phillips), a married man wrongfully accused of the murder of blackmailing femme fatale Mavis Marlowe (Constance Dowling). More centrally there is Martin Blair (Dan Duryea), a piano player/songwriter and ex-husband of the femme fatale, who teams up with Catherine Bennett (June Vincent), the loyal wife of the accused murderer, to clear the accused before he can be executed. Also critical to the plot are sinister nightclub owner Marko (Peter Lorre) and homicide detective Captain Flood (Broderick Crawford).

The film version of Black Angel was produced and directed for Universal by Roy William Neill, the last film he made before retiring. Neill was a stylish journeyman of a filmmaker, credited with directing well over 100 features, 55 of them silent. His most significant film, apart from Black Angel, is the 1934 pre-Code horror/noir Black Moon, about a young woman who brings back her knowledge of voodoo to the United States.

Neill also brought his talent for moody direction to no less than fourteen of the Basil Rathbone Sherlock Holmes features, including Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon, Sherlock Holmes in Washington, Sherlock Holmes Faces Death, The Spider Woman and The Pearl of Death. Roy Chanslor, who authored the screenplay adaptation of Black Angel, is best known for writing the novels on which the movie Westerns Johnny Guitar and Cat Ballou were based.

Chanslor’s March 6, 1946 screenplay is a less polished version of what was ultimately filmed. Among the changes: the name of the femme fatale is changed from Marcia in the screenplay to Mavis in the film; the name of the club proprietor (Peter Lorre’s character), is changed from McKee in the script to Marko in the film; and the name of the club is changed from Club Seven in the script to Rio’s in the film.

Some scenes have been modified or rearranged. A scene with homicide detective Flood in the script has been replaced by a scene where Marty and Catherine visit Catherine’s husband in jail. In the script, Catherine is a more active and aggressive character: it is her idea that she and Marty investigate the murder by getting jobs in the nightclub as the performers Martin (piano player) and Carver (singer), whereas in the movie it is Marty’s idea (one of the movie’s incidental pleasures is that Duryea does his own piano playing, and June Vincent does her own singing).

One amusing change: in the script, a newspaper columnist entices the nightclub proprietor to leave his club by offering him tickets to an Abbott and Costello preview; in the film it’s a Shostakovich concert (an event clearly more appropriate for an actor with the sophisticated persona of Peter Lorre).

There’s a romantic poignance at the heart of this story. When Marty and Catherine are operating as a team — investigating the murder or performing together as Martin and Carver — they seem made for each other, and Marty is able to rise above his former alcoholism. He seems much better suited for Catherine than her husband. Sadly, since this is a film noir, there will be no happy ending for Marty.

This is one of those films, like Vertigo, Psycho or The Sixth Sense, that becomes an entirely different — and richer — experience when viewed a second time, with knowledge of its surprising twist ending. In the case of Black Angel [spoiler], the twist is that the real murderer Catherine and Marty are looking for is, in fact, Marty himself, who has no memory of killing Mavis due to a condition of alcoholism-related amnesia that the movie refers to as “Korsakoff’s psychosis”. Chanslor’s screen adaptation differs in several respects from Woolrich’s book, and the film was apparently disliked by Woolrich himself. Regardless, Black Angel is now considered to be one of the finest of Woolrich-inspired noir films — faithful to the spirit, if not the letter, of his novel, its self-destructive protagonist and bleak ending an expression of pure unadulterated Woolrich.

Out of stock

Related products

-

CROSS CREEK (Feb 9, 1982) Rev Final Shooting script by Dalene Young

$750.00 Add to cart -

LOOT (ca. Sep 1969) Final Draft screenplay

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

![MON ONCLE D'AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French screenplay](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/MonOncleDAmeriqueFR-SCR_a-540x745.jpg)

Alain Resnais (director) MON ONCLE D’AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French film script

$2,500.00 Add to cart -

LONG WALK HOME, THE (Oct 13, 1988) Second draft film script by John Cork

$375.00 Add to cart