JOHNNY GOT HIS GUN (1971) Revised pre-production draft script by Dalton Trumbo [ca. 1968]

Dalton Trumbo (source, screenwriter) Vintage original revised pre-production draft film script, USA. Beverly Hills: The Bruce Campbell and Dalton Trumbo Company, [nd. but ca. 1968]. [1], v, 136 leaves plus lettered inserts. Quarto, mimeographed typescript, printed on rectos only of white, yellow and salmon stock. Brad bound. Chip from blank fore-edge of terminal leaf, not affecting text, otherwise very good or better.

An important anti-war script by the legendary Hollywood Ten member Dalton Trumbo, for the only film he ever directed.

An unidentified, undated, but revised pre-production draft of Dalton Trumbo’s own screenplay adaptation of his 1939 novel. A multitude of revises on various colored papers, as well as lettered inserted half-pages, suggests the script was still in flux, and a section preceding the opening of the script includes a brief history of the novel, and quotes international comments about it, clearly in an effort to generate studio interest in the project. We’ve handled two other drafts of this screenplay, both denoted “final” (but also with revises and similar collations), both dating from the first quarter of 1968. Trumbo also directed the 1971 release, starring Timothy Bottoms, Jason Robards, Donald Sutherland and Donald Barry. Trumbo won two awards at Cannes for his work on this film.

The anti-war novel Johnny Got His Gun by famously-blacklisted screenwriter, Dalton Trumbo (1905-76), was originally published in September 1939 (“three days before the beginning of World War II” as Trumbo himself notes in the introduction to this screenplay). Since the story takes place entirely within the mind of a wounded World War I soldier with no arms, no legs, no sight or hearing or any way to speak, it would seem an unlikely subject for a motion picture. Yet there was a 1940 radio adaptation by Arch Oboler with James Cagney in the role of the wounded soldier, and in 1964, Trumbo was approached by the renowned Spanish filmmaker, Luis Buñuel, to do a film version. There were script conferences with Buñuel in Mexico, “four-hour lunches which averaged out to about a bottle of wine an hour”, but “by the time I had the screenplay completed, the producer was out of money and Buñuel was back in Spain, broke.”

Then came the Vietnam War along with the mass protests against the war, and an American film production of Trumbo’s anti-war parable became suddenly viable. The present screenplay, said to have been completed by Trumbo in 1968, became the basis of a movie directed by Trumbo himself – his sole directing credit – and distributed in 1971.

Given the inherent difficulty of the material, the screenplay is something of a tour-de-force. It was roughly the 35th screenplay written by Trumbo, once a member of the Hollywood Ten, whose writing career – credited and uncredited – included such filmic landmarks as KITTY FOYLE, THIRTY SECONDS OVER TOKYO, A GUY NAMED JOE, Joseph H. Lewis’s GUN CRAZY, William Wyler’s ROMAN HOLIDAY, Otto Preminger’s EXODUS and Stanley Kubrick’s SPARTACUS.

The problem – how to make a movie out of a book that is essentially an interior monologue. Trumbo, now recognized as one of Hollywood’s greatest screenwriters, solves the problem with a wide variety of techniques, verging on the experimental – mixing fantasy with reality and flashbacks, stock footage with black and white and color footage – all of this indicated in Trumbo’s screenplay.

This draft screenplay is, in fact, significantly different from the movie ultimately made from it, and even more radically avant-garde. For example, in the screenplay the consciousness of Joe, the blind, deaf, quadruple amputee soldier (played in the film by Timothy Bottoms), is represented by a figure whom Trumbo refers to as the IMAGE – “He is Joe, completely nude and painted grey from head to foot. . . . It is visible as solid flesh to the audience at all times, but others who enter the room do not notice it because they cannot see it.” The IMAGE does not appear in the completed film.

Likewise, there are a couple of overtly symbolic sequences illustrated in the screenplay by a series of sequential frame drawings. One sequence is part of a flashback that shows the departure of Joe from his girlfriend, Kareen, at a train station as he leaves for war. In Trumbo’s illustrated conception, the two lovers, separating in long shot, see nothing but each other, the distance between them depicted by a field of black that grows larger and larger as they move further apart. The other illustrated sequence, referred to in the screenplay as the “Giraffe fantasy,” shows the necks and heads of two standing giraffes – the “bad giraffe” kicks the “good giraffe;” the “good giraffe” is “astounded” and kicks back; and so on. Neither of these sequences appears in the finished film.

However, the film does retain the screenplay’s mixture of fantasy, reality, and flashbacks. The reality, the scenes set in Joe’s hospital room, is shot in black and white; the flashbacks are shot in pastel colors, the “color of memory” while the fantasy sequences, e.g. a carnival scene where Joe is exhibited as a freak while his father acts as barker, are shot in vivid color. While this mixture of fantasy, reality, and flashbacks may be reminiscent of 1960’s art films like Fellini’s 8 ½, it should be noted that the same mixture of fantasy, reality, and flashbacks appears in Trumbo’s original novel, published in 1939.

The screenplay has a more Brechtian opening than the film, with a curtain opening to reveal a black screen, underneath which we hear the sounds of rifle shots. This segues into stock footage from 1917 showing “PATRIOTS, PRINCES, MARCHING REGIMENTS, ANTHEMS, EXHORTATIONS” followed by the departure scene on the railway platform where we hear songs like “Over There” and “Johnny get your gun, get your gun, get your gun”, the latter of which provided Trumbo’s novel with its title. The movie opens differently – we get the stock footage, but not the songs, and the first scene we see with actors is the hospital room, shot in black and white, where Joe wakes up after being wounded. While many of the same fantasy sequences and flashbacks appear in both the screenplay and the film, in the film they are presented in a different order.

Two other notable differences between screenplay and film. In the screenplay there are repeated images of the German shell that ultimately wounds Joe as it is being manufactured and shipped to the battlefield, intercut with or superimposed over scenes of Joe going to war, as if to imply an unavoidable destiny. The shell does not appear in the completed film. The screenplay and film’s most sympathetic character is a young nurse (Diane Varsi) who appears late in the narrative. It is she who first attempts to communicate with Joe, spelling out the letters of M-E-R-R-Y C-H-R-I-S-T-M-A-S with her fingers on his chest. In the screenplay, but not the movie, she goes even further, compassionately putting her hand underneath Joe’s sheets to masturbate him.

How much of the screenplay, if any, can be attributed to Buñuel, is a matter of pure speculation. The most Buñuel-like scenes are the fantasy sequences involving Joe and Jesus Christ (played in the film by Donald Sutherland). They have a tone that is very similar to the scenes involving Christ in Buñuel’s THE MILKY WAY (1969). However, these same scenes, or scenes very much like them, appear in Trumbo’s original novel.

Despite it being as close as it is to his 1939 novel, Trumbo’s 1971 film of JOHNNY GOT HIS GUN inevitably reminds one of other anti-war art films released during the same Vietnam period: Richard Attenborough’s OH! WHAT A LOVELY WAR (1969) and George Roy Hill’s SLAUGHTERHOUSE-FIVE (1972).

Out of stock

Related products

-

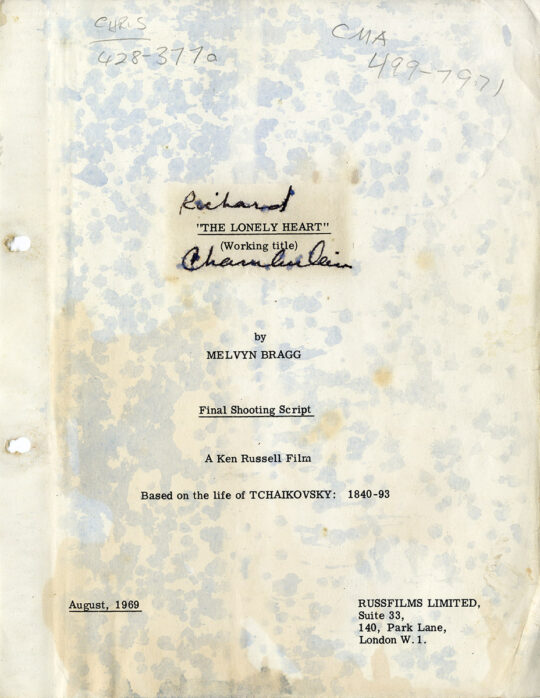

Ken Russell (director) THE MUSIC LOVERS [working title: THE LONELY HEART] (1969) Final shooting script

$3,000.00 Add to cart -

![MON ONCLE D'AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French screenplay](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/MonOncleDAmeriqueFR-SCR_a-540x745.jpg)

Alain Resnais (director) MON ONCLE D’AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French film script

$2,500.00 Add to cart -

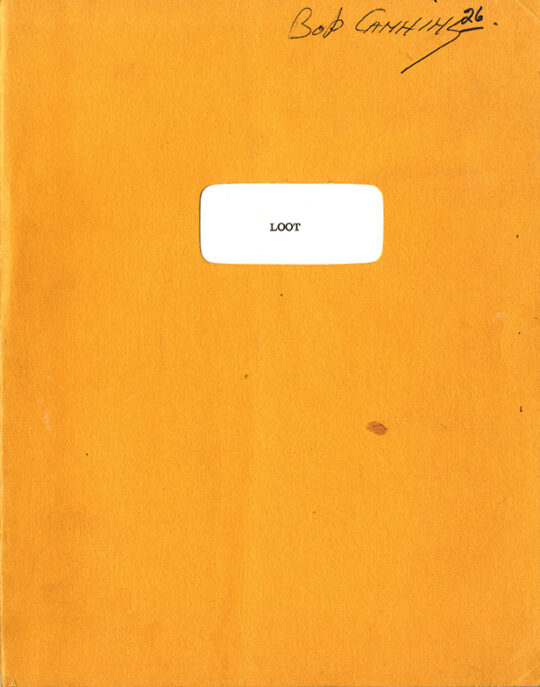

LOOT (ca. Sep 1969) Final Draft screenplay

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

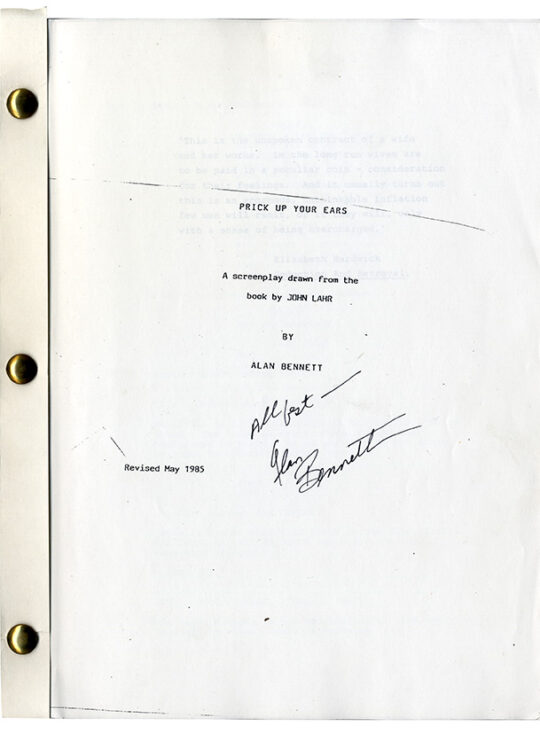

PRICK UP YOUR EARS (May 1985) Revised film script

$650.00 Add to cart

![JOHNNY GOT HIS GUN (1971) Revised pre-production draft script by Dalton Trumbo [ca. 1968]](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/JohnnyGotHisGunSCR.jpg)

![JOHNNY GOT HIS GUN (1971) Revised pre-production draft script by Dalton Trumbo [ca. 1968] - Image 2](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/JohnnyGotHisGunSCR_c.jpg)

![JOHNNY GOT HIS GUN (1971) Revised pre-production draft script by Dalton Trumbo [ca. 1968] - Image 3](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/JohnnyGotHisGunSCR_b.jpg)