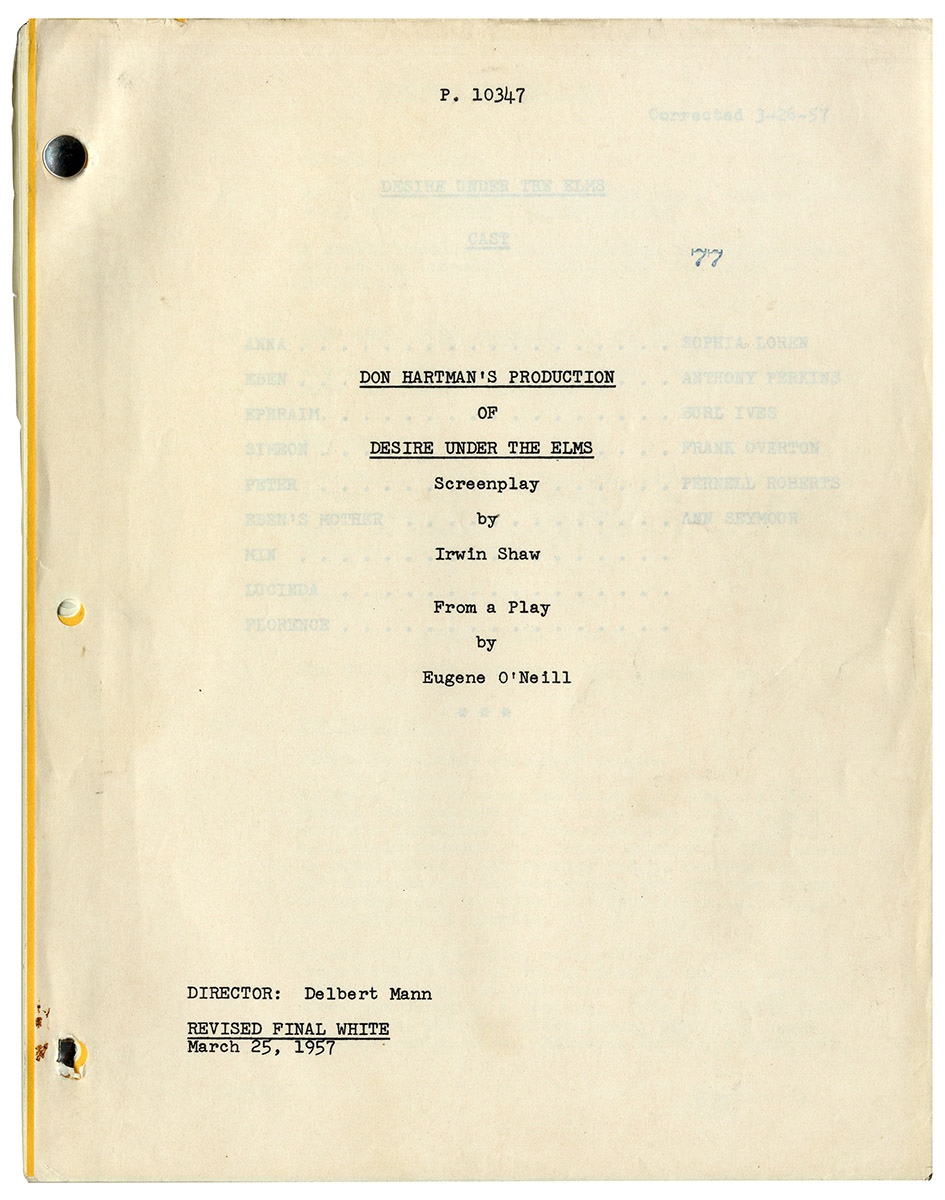

DESIRE UNDER THE ELMS (Mar 25, 1957) Revised Final White script by Irwin Shaw

[Hollywood: Paramount Pictures], 1957. Vintage original film script, 11 x 8.5″ (28 x 22 cm.) dated March 25, 1957, with one revision on orange paper dated March 29, 1957. Self-wrappers, brad bound, mimeograph, 123 pp. (pp. 34-36 are not present), just about fine.

By the time DESIRE UNDER THE ELMS premiered at New York’s Provincetown Playhouse in 1924, its author, Eugene O’Neill, had already established himself as America’s leading dramatist, having previously won Pulitzer Prizes for his first published play, BEYOND THE HORIZON, in 1920, and for the hit play, ANNA CHRISTIE, in 1922. Like his later great work, MOURNING BECOMES ELECTRA, DESIRE UNDER THE ELMS was O’Neill’s attempt to adapt the plot and themes of a Greek tragedy to a 19th century New England setting, in this case, the myth of Theseus, Hippolytus, and Phaedra, the story of a son who falls in love with his stepmother, his aging father’s new young wife.

The screenplay for the 1958 film adaptation, directed by Delbert Mann, was written by Irwin Shaw, a novelist and screenwriter best known for his novels, The Young Lions, Two Weeks in Another Town and Rich Man, Poor Man, each of which was successfully adapted to the screen. The film version of DESIRE UNDER THE ELMS starred Burl Ives as Ephraim Cabot, the father, Anthony Perkins as Eben Cabot, the son, and Sophia Loren as Anna, the stepmother.

Irwin Shaw’s screenplay is faithful to the spirit of O’Neill’s play but quite free in its adaptation to the film medium. For example, where the play begins outside the Cabot farmhouse, a scene involving young Eben and his two stepbrothers building a fence out of rocks, Shaw’s screenplay begins by illustrating the drama’s backstory. We see Eben as a young boy with his mother, his father’s second wife, a character who is spoken of but never appears in the play. Specifically, we see her pointing out to the boy the spot where his father buries his gold. We then dissolve to 24-year-old Eben standing over his mother’s grave. All of this precedes the action in O’Neill’s play. Whereas the stepmother, Ephraim’s third wife, named Abbie in the play, is a hardened but sensual woman of 35, in the movie she is renamed Anna and written as a 27-year-old Italian woman to accommodate the talents and persona of Sophia Loren who portrays her.

The movie’s most memorable scene, the seduction of Eben by Anna, is presented almost exactly as it was written in O’Neill’s original play. On the other hand, the screenplay adds a Hitchcockian suspense scene. Anna and Eben are in a hayloft, making love while old Ephraim is supposed to be in town purchasing supplies. Ephriam, unfortunately, returns earlier than expected. We see him below entering the barn, while on the upper left of the screen we see Anna and Eben cowering in the loft about to be discovered as Ephraim starts to ascend the ladder leading up to it. At the last second, however, he turns back.

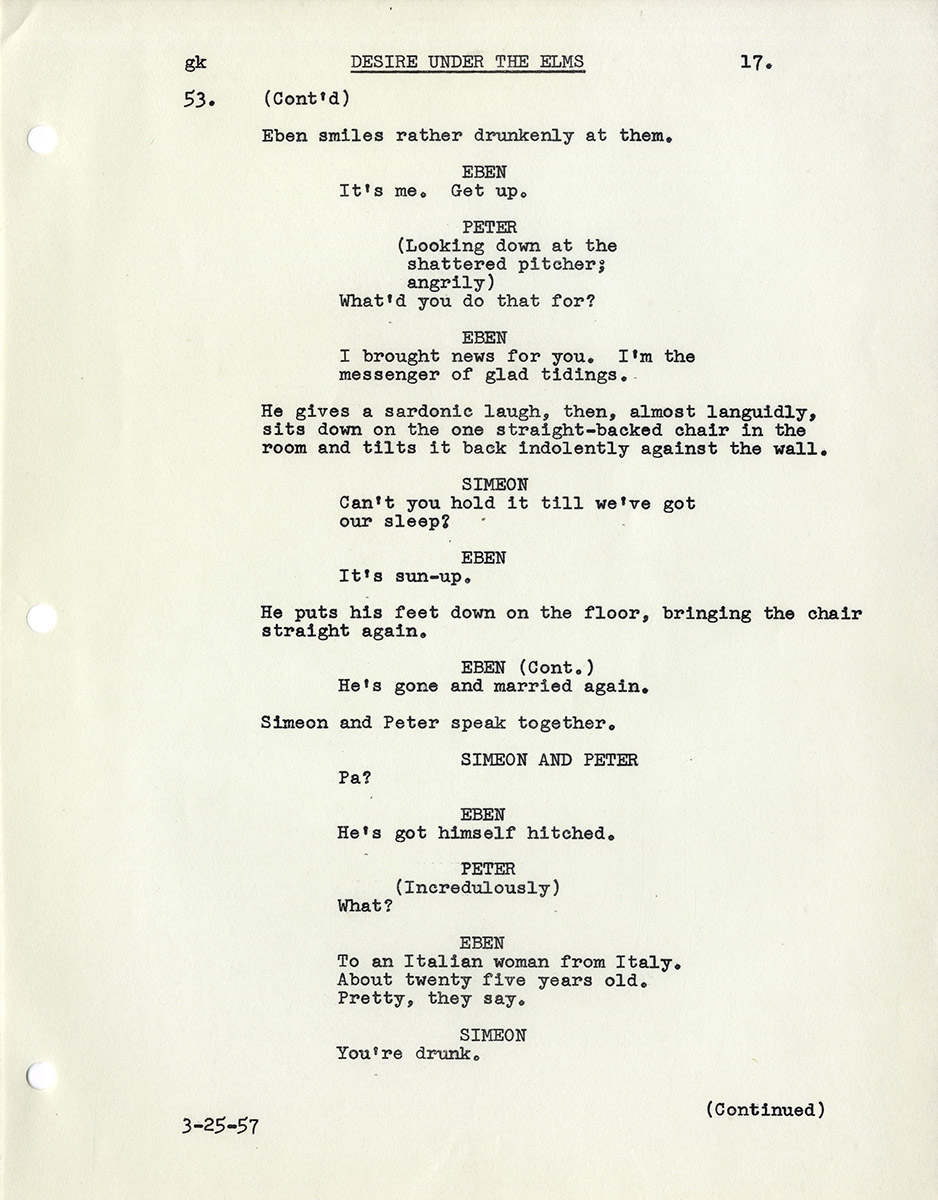

Another major difference between O’Neill’s play and Shaw’s screenplay: in the play’s first act, Eben’s two older stepbrothers leave for California to look for gold, never to return; in the screenplay, the two stepbrothers, having found gold, briefly return to the farm in the movie’s last act, accompanied by their wives, a pair of San Francisco gold digger types. It’s a credit to Shaw’s skills as a screenwriter that the dialogue he adds is indistinguishable from that written by O’Neill.

The drama’s essential theme is the struggle between Anna and Eben for ownership of the farm, a property that originally belonged to Eben’s mother. The old man promises he will bequeath the farm to Anna if she bears him a son. Accordingly, Anna seduces Eben to become pregnant, but in the course of their affair she falls genuinely in love with him. [SPOILER ALERT] Ultimately, to prove her love for Eben, to prove in fact that she didn’t become pregnant simply to secure ownership of the property, Anna murders the baby. The story ends with Eben accepting his complicity and guilt.

There are echoes, of course, of Sophocles’ MEDEA and OEDIPUS REX. In the great dramas of Euripides, HIPPOLYTUS (the Phaedra story) and THE BACCHAE, sex is presented as an overpowering force, impossible to resist, often leading to tragic consequences. DESIRE UNDER THE ELMS, both the original play and the film version, successfully reimagine Euripidean tragedy in modern terms.

On a more personal level, DESIRE UNDER THE ELMS deals with some of the same familial issues — O’Neill’s mixed feelings about his father, mother, and brother — that are dramatized in his late autobiographical play, LONG DAY’S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT.

Footnote: Anthony Perkins would replay the Theseus/Hippolytus/Phaedra situation in at least two more subsequent films, in Jules Dassin’s PHAEDRA (1962) with Raf Vallone as the father, and in Claude Chabrol’s TEN DAYS WONDER (1971) with Orson Welles as the domineering dad.

Out of stock

Related products

-

Sidney Lumet (director) PRINCE OF THE CITY (Jan 1980) Final Draft film script

$950.00 Add to cart -

(Jewish American film) THE CHOSEN (Jul 25, 1980) Film script

$400.00 Add to cart -

SEARCHING WIND, THE (Nov 7, 1946) Final White script by Lillian Hellman

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

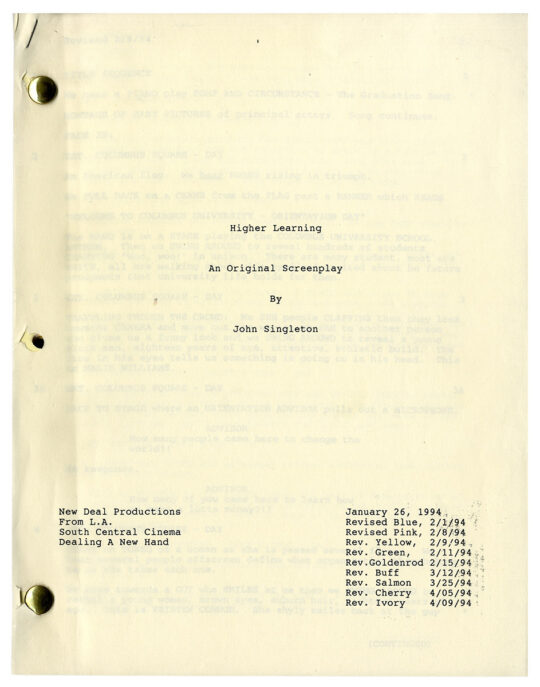

John Singleton (writer, director) HIGHER LEARNING (Jan 26, 1994) Rainbow film script

$500.00 Add to cart