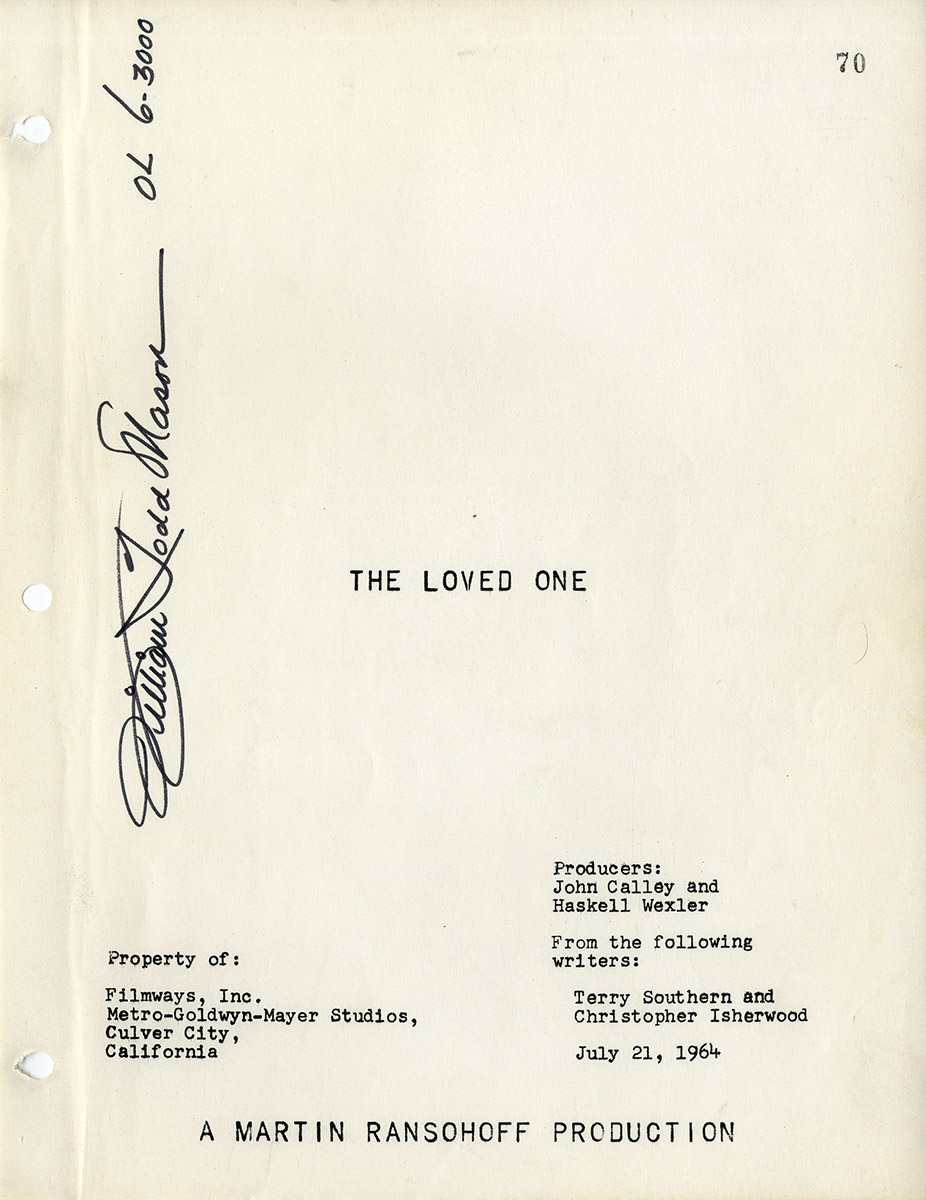

Evelyn Waugh (source), Terry Southern, Christopher Isherwood (screenwriters) THE LOVED ONE (1964) Film script

Culver City, CA: Filmways, Inc., 1964. Vintage original film script, 11 x 8.5″ (28 x 22 cm.), plain wrappers, brad bound, mimeograph, 154 pp. Script belonged to uncredited crew member William Todd Mason, with his name and phone number in holograph ink on the title page, and some brief penciled annotations on three pages. Laid in is a corner stapled, three-page staff and crew list, with two name additions in holograph red ink on the second page. Included is a vintage original studio still photograph from the film. The cast and crew list is very good+, with marginal creasing. Script and photo fine.

From Waugh to Isherwood to Southern

The Loved One: An Anglo-American Tragedy (1948) was a short satirical novel by British author Evelyn Waugh, inspired by a 1947 visit to Los Angeles paid for by a film studio, MGM, that was interested in making a film adaptation of one of Waugh’s earlier novels, Brideshead Revisited (the film was never made). The targets of Waugh’s satire were Hollywood, the funeral business, newspaper advice columnists, and the community of English actors and other artists living in L.A. Waugh offered the novel to The New Yorker magazine which surprisingly declined to publish it on the grounds that two of its subjects had already been thoroughly lampooned in the novels of Nathanael West, specifically, West’s The Day of the Locust (Hollywood) and Miss Lonely Hearts (advice columnists). Ironically, it was MGM who ended up producing the 1965 film version of Waugh’s satire.

Christopher Isherwood, an English expatriate living in L.A., was a perfect choice to write the initial screenplay draft. At that point, Isherwood was best known for writing The Berlin Stories, an observational semi-autobiographical work that was eventually adapted into the play, I AM A CAMERA, and later a famous musical, CABARET. He was particularly well-suited for the “English” aspects of Waugh’s story. One suspects it was Isherwood who was responsible for modeling certain characters after real life figures. Youthful studio executive D.J., Jr. (Roddy MacDowall) appears to be based on Darryl F. Zanuck, Jr., the son of mogul Darryl F. Zanuck, while Sir Francis Hinsley (John Gielgud) in Isherwood’s screen adaptation combines elements of two other English expatriates working in Hollywood, designer Cecil Beaton and film director James Whale (the swimming pool suicide), both — like Isherwood — gay. Terry Southern, the American hipster co-author of the porn pastiche, CANDY, and the cinematic black comedy, DR. STRANGELOVE: OR HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE BOMB, was brought in to punch up the satire and black humor. Thanks to Southern, the movie lived up to its tag-line, “The Motion Picture with Something to Offend Everyone!” Isherwood and Southern’s smart screenplay thoroughly modernizes Waugh’s plot, adding such ideas as the Blessed Reverend’s plan to clear his cemetery property for redevelopment by blasting the “stiffs” into outer space!

Script vs. Screen

This appears to be the final, or close-to-final, shooting script. The scene structure and dialogue are fairly close to the completed film, and the script even indicates specific L.A. locations where certain scenes were expected to be shot. It’s clear, however, that the script continued to be modified during the shooting and editing process, and a number of gags and bits of business were added — most likely by Southern — although director Tony Richardson and improvisational actors like Jonathan Winters (playing two roles) should also be credited. Another key collaborator was maverick cinematographer Haskell Wexler, who was one of the film’s producers and responsible for its distinctive black and white look, a look that borrowed heavily from contemporary European art films like LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD and Fellini’s 8 1/2.

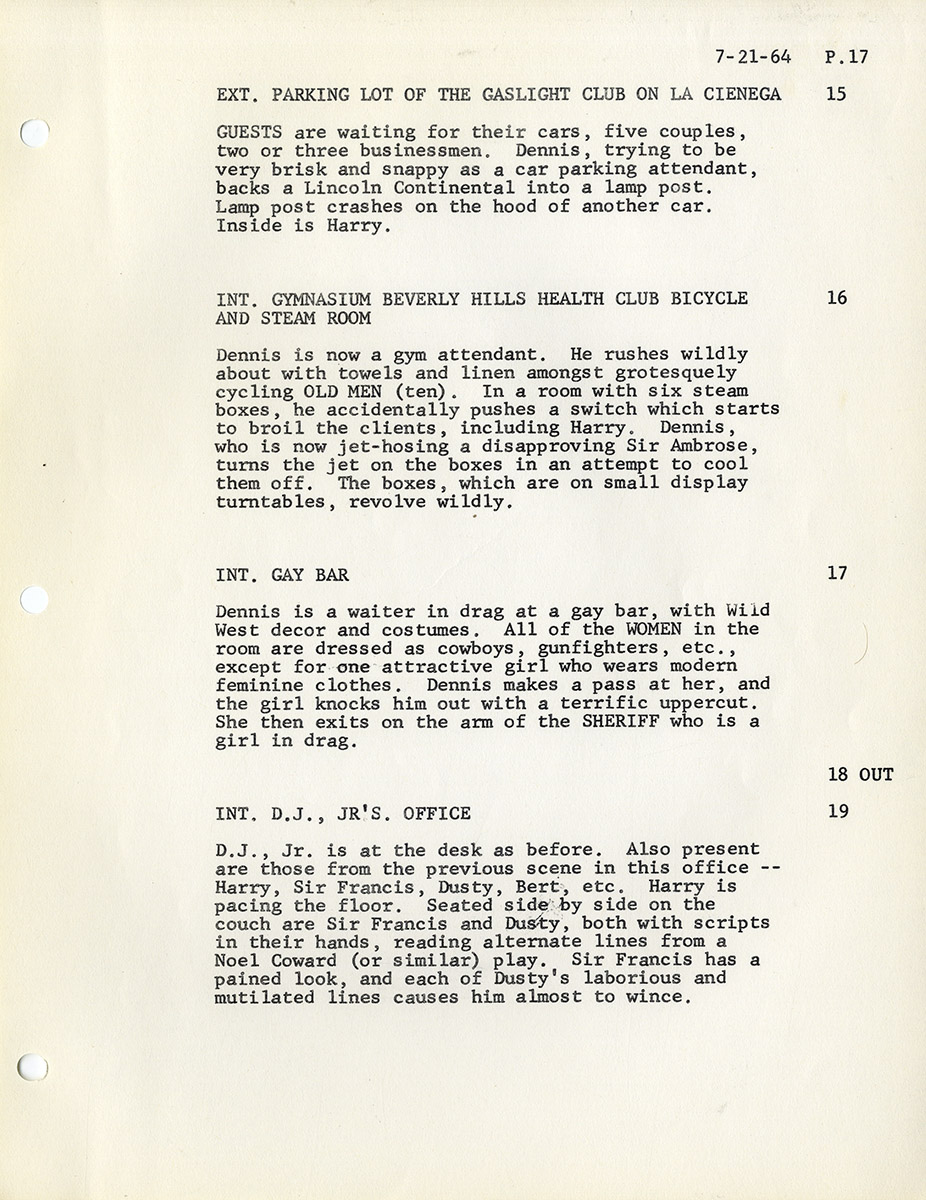

Among the changes: The film’s opening has been streamlined. In the screenplay, the film’s protagonist Dennis Barlow (Robert Morse) arrives at the L.A. airport, is interviewed by a hostile customs agent (James Coburn), wanders through the airport, talks to a girl at Travelers Aid, and is then seen driving a convertible on the freeway. In the movie, as soon as the customs agent asks Barlow where he will be staying and Barlow answers “with my uncle, Sir Francis Hinsley,” we cut (while Barlow continues in voiceover) to the first scene of Sir Francis (Gielgud) having a production meeting with D.J., Jr. at the Megapolitan Pictures studio.

In the montage of jobs taken by Barlow before he finds work at the Happier Hunting Grounds pet cemetery, the screenplay includes a scene of him working in a gay bar. We know a scene like this was shot but later deleted, because stills of it exist showing Robert Morley’s character (Sir Ambrose Abercrombie) in drag.

A scene where Sir Francis, after being terminated, talks to a Mexican janitor at the studio has been eliminated.

Dr. Wilbur Kenworthy (Jonathan Winters), the proprietor of the massive Whispering Glades cemetery park is referred to in the screenplay as “The Dreamer.” In the movie, he is referred to as the “Blessed Reverend.” The recorded welcoming speech given by a statue of the Blessed Reverend to park visitors has been augmented by such lines as, “Where sorrow became the mewing of tiny kittens and splash of precious duck babies at play.”

In the movie, the scene where Whispering Glades’ Counsel Starker (Liberace) attempts to sell Barlow a coffin has been embellished with lines explaining the differences between coffins that are “waterproof”, “dampness proof” and — best of all — “moisture proof.”

In the scene where an elderly Jewish couple is turned away from the park because it doesn’t bury people of that kind, the friendly hostess informs the couple that there are other fine establishments which could accommodate them. In the movie, she adds, “Forest Lawn, for example,” no doubt to avoid any potentially libelous confusion (heaven forbid) between the real Forest Lawn cemetery and the fictional Whispering Glades.

Different drafts of this film have over time turned up. This is the only draft known to this cataloguer to cite both Southern and Isherwood as writers. Given the great importance of both authors in the literary canon, this has always been a “holy grail” script to find.

Out of stock

Related products

-

Sidney Lumet (director) PRINCE OF THE CITY (Jan 1980) Final Draft film script

$950.00 Add to cart -

LONG WALK HOME, THE (Oct 13, 1988) Second draft film script by John Cork

$375.00 Add to cart -

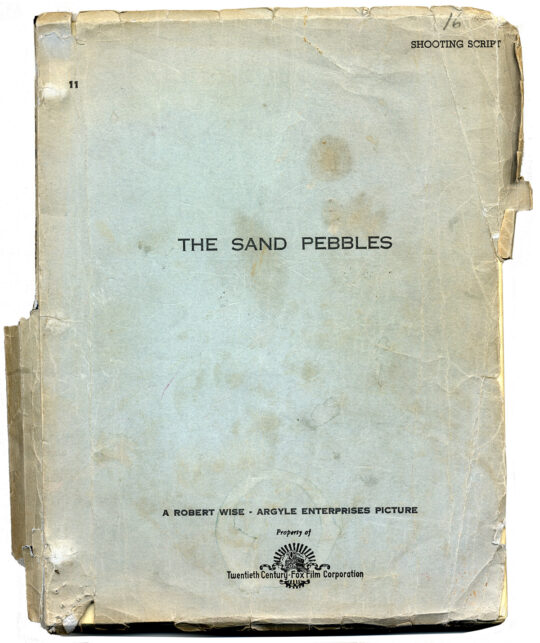

SAND PEBBLES, THE (Nov 1, 1965) Shooting script by Robert Anderson

$1,150.00 Add to cart -

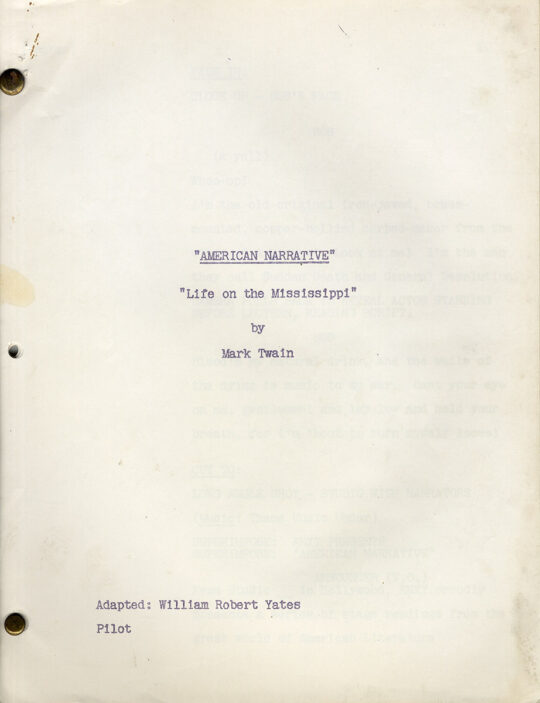

Mark Twain (source) LIFE ON THE MISSISSIPPI (ca. 1956) TV script adapted by William Robert Yates

$300.00 Add to cart