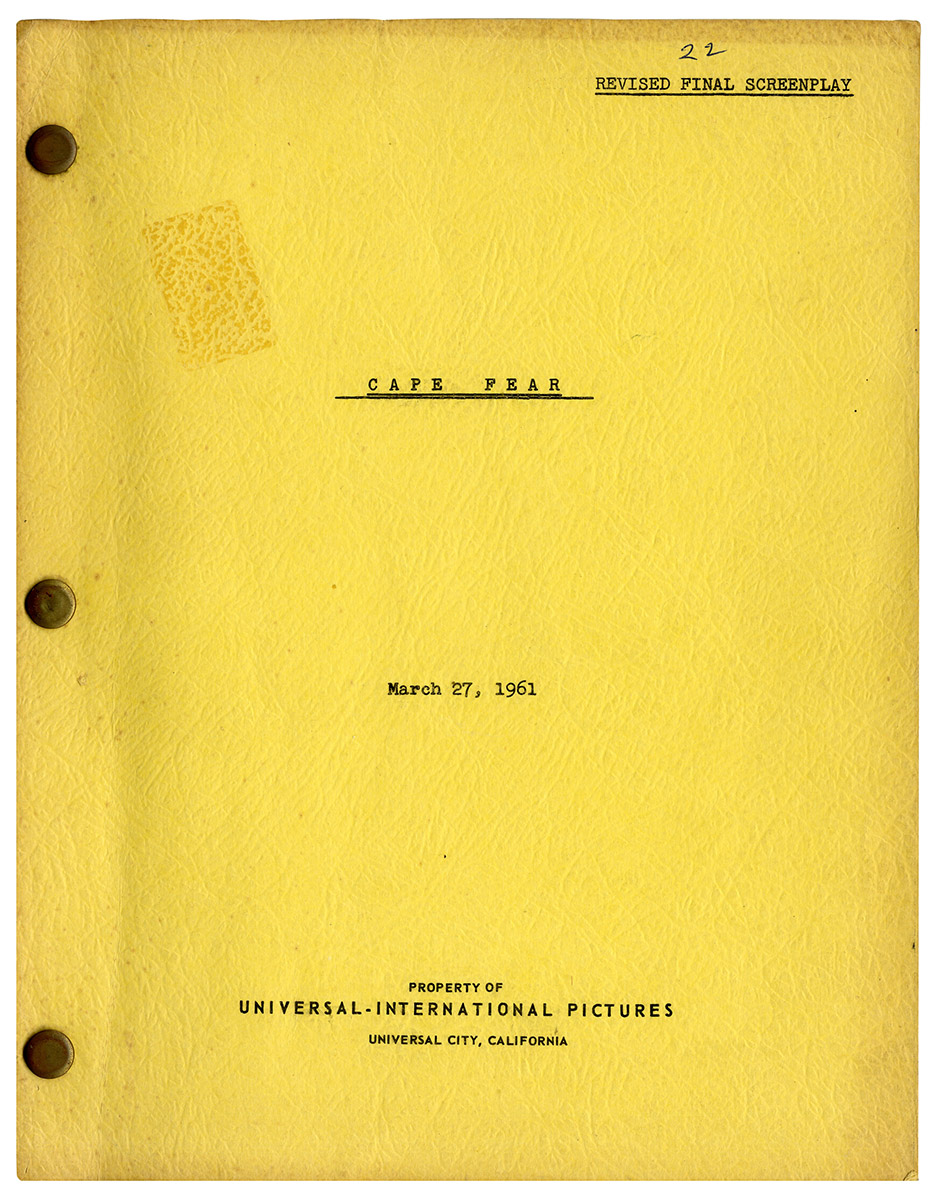

(Film noir) CAPE FEAR (Mar 27, 1961) Revised final screenplay by James R. Webb

[Los Angeles]: Universal-International, 1961. Vintage original film script, 11 x 8 1/2″ (28 x 22 cm.), printed studio wrappers, brad bound, mimeograph, eye-rest green stock, near fine. Designated as Revised Final Script by James R. Webb.

Robert Mitchum, though generally acknowledged as one of the greatest stars of Hollywood’s classic era, was frequently underrated as an actor. He made it look so easy. Yet, in addition to the stoic leading men he played so often and so well, Mitchum also portrayed two of the most terrifyingly convincing psycho villains in screen history: the Reverend Harry Powell in Charles Laughton’s Night of the Hunter (1955) and the vengeful southern ex-con Max Cady in J. Lee Thompson’s Cape Fear (1962). Cape Fear not only gave us Robert Mitchum in one of his two finest villain roles, it also provided Gregory Peck with one of his two most iconic roles as an attorney, the other one being his Oscar-winning performance as Atticus Finch in Robert Mulligan’s To Kill a Mockingbird released the same year.

Lee Thompson was a British-born director best known for the action/adventure film The Guns of Navarone (1961), which also starred Gregory Peck. His Cape Fear was based on John D. MacDonald’s novel The Executioners. A prolific author of crime and suspense novels, MacDonald was known particularly for the series of 21 novels he wrote featuring the self-described “salvage consultant” Travis McGee.

MacDonald’s novel was brilliantly adapted to the screen by James R. Webb, a writer with more than 30 screenplays to his credit, the majority of them in the Western genre. A year after Cape Fear was released, Webb won the Academy Award for his original screenplay for the Cinerama epic How the West Was Won (Henry Hathaway, John Ford, George Marshall, 1963), and the year after that he authored the equally epic Cheyenne Autumn (1964) for director John Ford.

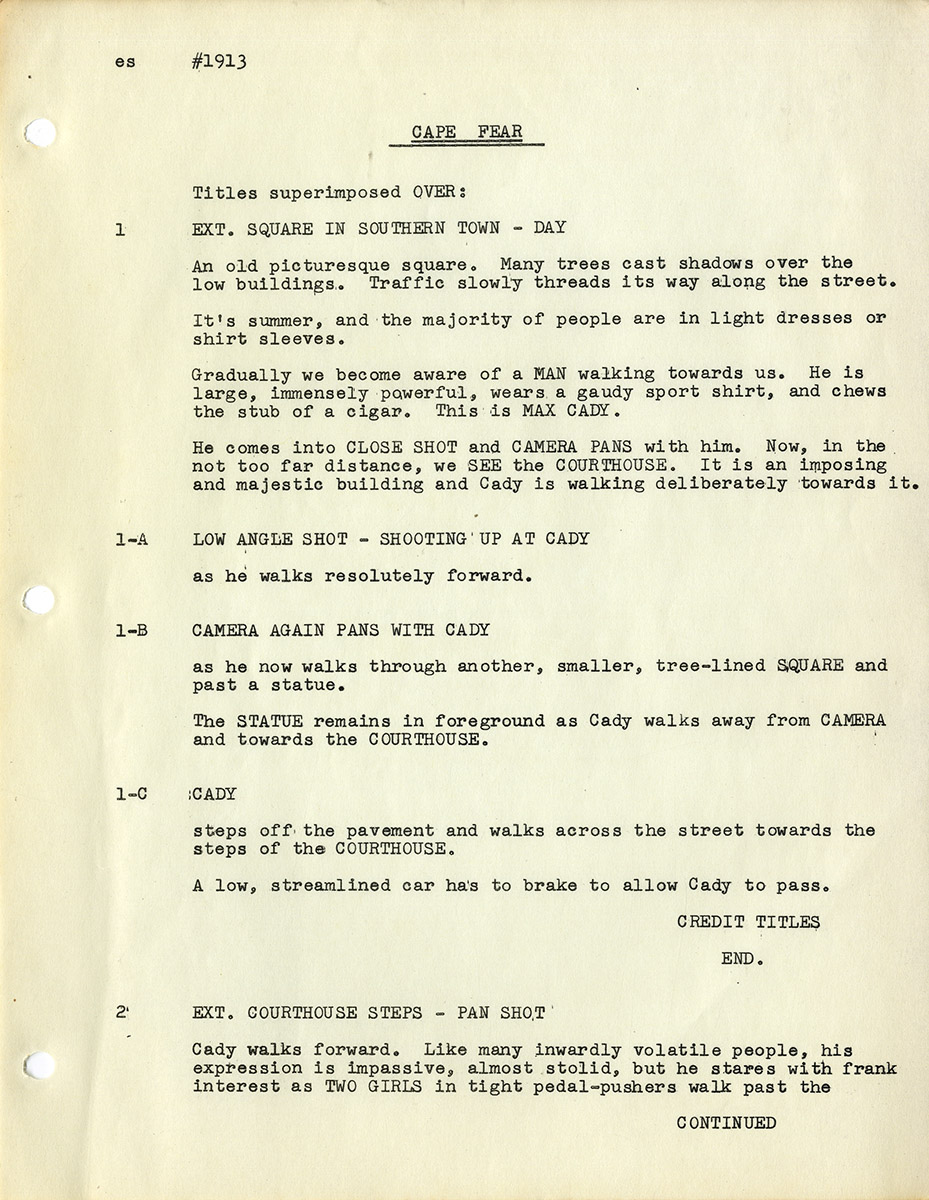

Cape Fear is a noir (or neo-noir) blend of horror and suspense in the stalker subgenre. Peck’s attorney, Sam Bowden, and his attractive wife and daughter are pursued by Mitchum’s supernaturally clever ex-con Max Cady because Cady believes Bowden was responsible for his imprisonment in the first place. Cady’s plan is to terrify Bowden and his family without ever being caught doing anything that could get him re-arrested. When, for example, the family dog is horrifyingly poisoned, there is no way Bowden’s friends in the police department can prove it was Cady who did the poisoning. Cady engages a smart lawyer to threaten Bowden and the police with charges of harassment, and when a desperate Bowden hires a trio of thugs to rough Cady up, Cady sues him for assault and threatens to get him disbarred.

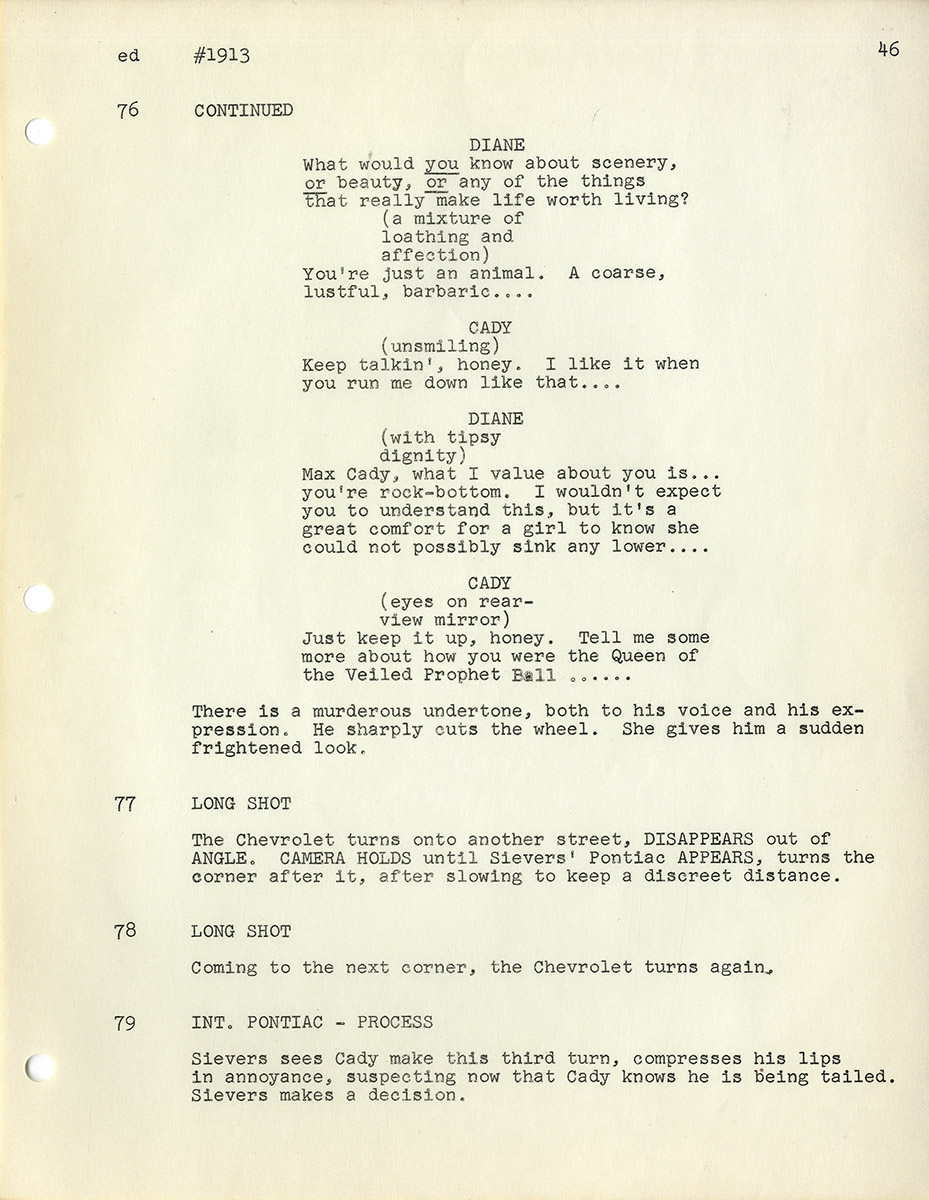

Where Cape Fear broke new ground for its time was in the overtly sexual nature of Cady’s threat. The leering Cady follows Bowden’s family everywhere through their town. He makes obscene phone calls to Bowden’s wife (Polly Bergen) and stalks Bowden’s nubile daughter (Lori Martin) through a schoolyard. He picks up an attractive woman (Barrie Chase) in a bar and subjects her to unspeakable physical abuse, knowing this particular woman will be too traumatized and too protective of her reputation to press charges or testify against him in court.

In a significant departure from MacDonald’s source novel, screenwriter Webb sets the third act of his screenplay aboard a houseboat on the Cape Fear River (hence, the film’s title) where Bowden uses his family as bait to lure Cady into a fatal confrontation. But before he is defeated, Cady murders a deputy that Bowden had secured to protect the family, and nearly (or perhaps actually) rapes Bowden’s wife (Webb’s third act houseboat climax was also used by Martin Scorsese in his 1992 remake of this film. Scorsese also recycled the 1962 film’s superlative Bernard Herrmann score).

The principal differences between Webb’s “Revised Final Screenplay” and the completed film are largely a matter of editing. There are no substantial differences between what happens in the screenplay and what occurs in the movie, but many lines of dialogue have been trimmed or deleted altogether to create a tighter narrative. For example, after the poisoning of the family dog, the screenplay references “three dogs in this general neighborhood poisoned today.” That brief discussion is omitted from the film. The screenplay has a scene where, after his daughter has been stalked, Bowden recruits three tough guys to attack Cady. That scene is eliminated from the movie which cuts directly from the scene of Bowden and his wife deciding they need more than police protection to the scene of the thugs beating Cady up. For reasons of censorship, the word “rape” is never spoken in the film, though it is used in the screenplay.

The film’s essential ethical dilemma is stated explicitly by Bowden’s wife when she says “A man like that doesn’t deserve civil rights.” Bowden ultimately shows his fidelity to due process and law and order when at the screenplay’s conclusion he permits Cady to live, knowing that the rapist and murderer will spend the rest of his life in a jail cell. Cape Fear is a horror film with a real human monster as terrifying as any supernatural creature and arguably even more disturbing. Webb’s perfectly constructed screenplay provided the basis for one of the most harrowing motion pictures ever made.

Grant, p. 106: “Among the most white-knuckle of all noirs… packs prodigious punch largely because of Mitchum — strutting, sneering, falsely smiling, a ticking time bomb ready to explode at any moment into sadistic violence.”

Out of stock

Related products

-

CROSS CREEK (Feb 9, 1982) Rev Final Shooting script by Dalene Young

$750.00 Add to cart -

Mark Twain (source) LIFE ON THE MISSISSIPPI (ca. 1956) TV script adapted by William Robert Yates

$300.00 Add to cart -

SAND PEBBLES, THE (Nov 1, 1965) Shooting script by Robert Anderson

$1,150.00 Add to cart -

![CHINATOWN [ca. 1973] Jack Nicholson's copy of early draft film script by Robert Towne](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/ChinatownSCR_a-540x693.jpg)

CHINATOWN [ca. 1973] Jack Nicholson’s copy of early draft film script by Robert Towne

$18,500.00 Add to cart