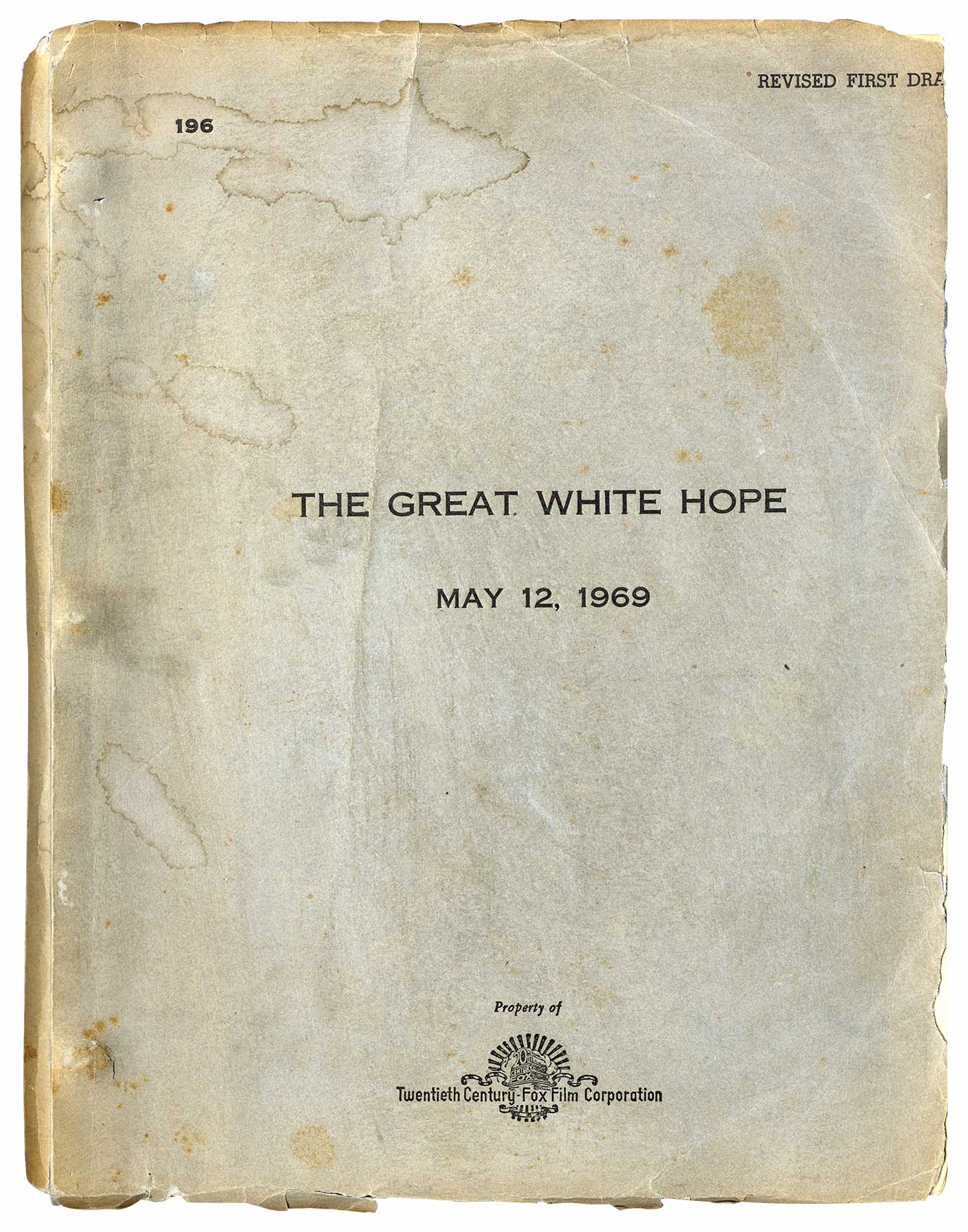

GREAT WHITE HOPE, THE (1970) Revised 1st Draft script dated May 12, 1969

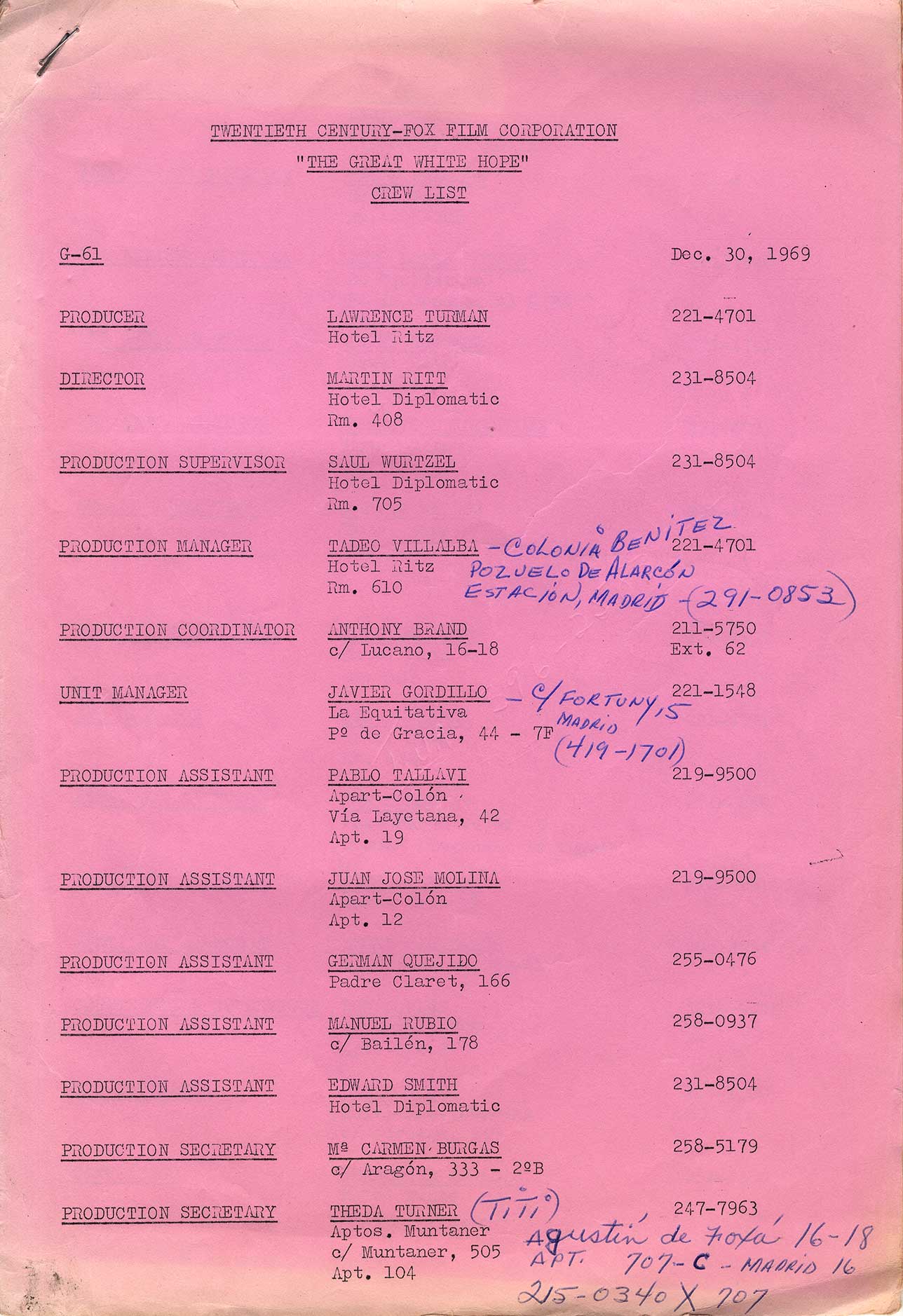

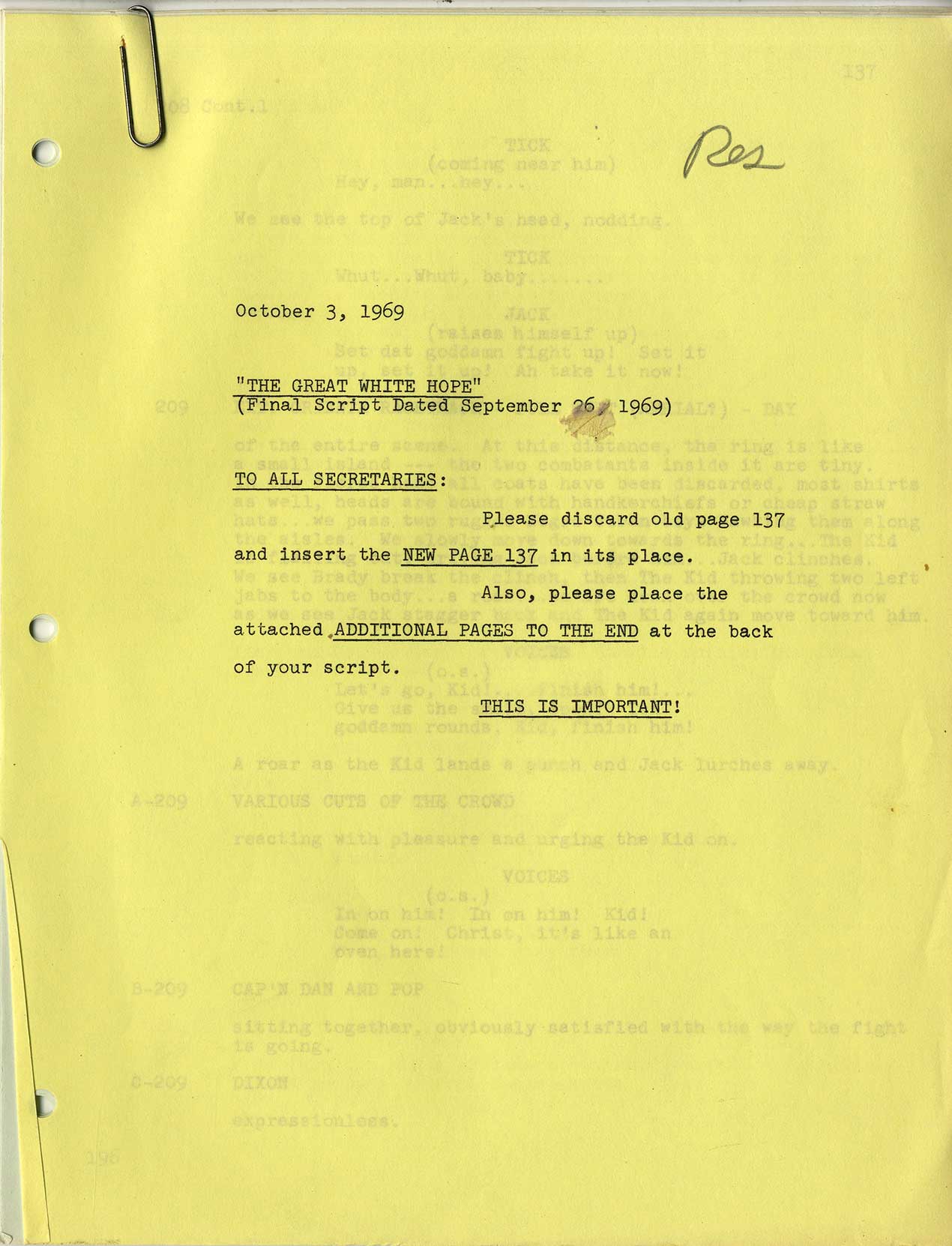

Revised First Draft, Los Angeles: Twentieth Century Fox, May 12, 1969. Vintage original film script, quarto, printed wrappers, brad bound, mimeograph, 155 pp. Laid in are several pages of revisions, beginning with page 137, and a notice “to all secretaries” to add said revisions, dated October 3, 1969. Also included are four vintage black-and-white reference photographs from the film, as well as memos and contact lists having to do with the Barcelona portion of the shoot. Laid-in revisions dated October 3, 1969: 16 leaves (1 yellow “notice” page, 15 eye-rest green stock).

Wrapper chipped at yapped edges, JUST ABOUT FINE in VERY GOOD- wrappers. Revisions bound with paper clip (a few pages of revisions with marginal wear, VERY GOOD). Film photos NEAR FINE.

Playwright, screenwriter, and theater director Howard Sackler (1929-82) was a classmate of Stanley Kubrick’s at William Howard Taft High School in the Bronx, New York, and made his film debut as the screenwriter of Kubrick’s first two independently produced features, FEAR AND DESIRE (1953) and KILLER’S KISS (1955). KILLER’S KISS was a story about a boxer, a theme that Sackler would return to in his best known work, THE GREAT WHITE HOPE, a play that premiered in Washington, D.C. in 1967, opened in New York in 1968, and received the Tony Award for Best Play and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1969.

Sackler’s play, set in the years 1910 through 1915, starred James Earl Jones as Jack Jefferson – based on the real-life Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight boxing champion of the world – and Jane Alexander as Eleanor Bachman, his white wife. Both Jones and Alexander received Tony Awards for their portrayals, and in 1970, producer Lawrence Turman (THE BEST MAN, THE GRADUATE) made a film version with a screenplay by Sackler, and with Jones and Alexander repeating the roles they had created on stage (both ultimately nominated for Academy Awards for their performances).

The 1970 film version of THE GREAT WHITE HOPE was directed by Martin Ritt (1914-1990), a former television and theater director, remembered today for socially conscious movies like EDGE OF THE CITY (1957), HUD (1963), THE FRONT (1976), and NORMA RAE (1979). Ritt was also known for his work with black actors, having directed Sidney Poitier in EDGE OF THE CITY and PARIS BLUES (1961), James Earl Jones in THE GREAT WHITE HOPE, and after that, Paul Winfield and Cicely Tyson in what might be his best film, SOUNDER (1972), a movie about black sharecroppers during the Great Depression.

Director Ritt was generally faithful to Sackler’s GREAT WHITE HOPE screenplay. Even the movie’s credit sequence is filmed almost exactly as described in Sackler’s screenplay, with a horizontally split screen showing the film’s titles on the lower half, representing the base of a boxing ring, and the top half showing “the legs of the fighters, a black man’s and a white man’s, crossing back and forth in the middle of a hot round ….”

The play’s dialogue is occasionally trimmed in the transition from screenplay to screen, for example, the first line of the screenplay in which the white heavyweight boxing champion challenged by Jefferson declares:

Get Burke, or Kid Foster. Big Bill Brain! I ain’t gonna fight no dinge.

The movie’s first line of dialogue is simply:

I ain’t gonna fight no dinge.

Occasionally, something is added. For example, in the first scene, where the promoters are discussing where “the fight of the century” should be held. In the screenplay, the dialogue reads:

CAP’N DAN

No big towns, Pop. You’ll have every n*gg*r and his brother jamming in there.

POP

How about Tulsa? Denver? Reno?

SMITTY

Hey, Reno!

The movie amends Smitty’s line as follows:

SMITTY

Hey, Reno! That’s white man’s country!

Dialogue is trimmed when possible. A brief screenplay scene involving the fight promoters is omitted entirely (though it might have been shot and cut later during the editing of the film). But on the whole, the movie is scrupulously faithful to the dialogue of Sackler’s play and screenplay.

On the other hand, like most film directors shooting someone else’s screenplay, director Ritt tends to disregard the screenplay’s shot descriptions and indications of camera angles. This is apparent in any of the film’s big visual set pieces. For example, in the introduction to the town of Reno where the championship fight is going to be held, Sackler’s screenplay begins the sequence with a shot looking down the street towards the stadium, “red, white and blue bunting everywhere … the street milling with white men, coatless, sweaty, rowdy, excited …“. Ritt’s filming of that same sequence begins with a steam locomotive entering the town, followed by boxcars full of fight attendees, and there is a parade with a red-uniformed marching band, none of which is indicated in the screenplay.

Ritt likewise disregards the screenplay’s suggested transitions between scenes, preferring to create transitions of his own. For example, the transition from the ending of the big fight to the celebration that night in the “Negro Honky-Tonk District” — In Sackler’s screenplay description, the fight sequence ends with a pan upward from the shocked crowd to “a shot of the blinding sun above“, then cuts to a close-up of “the bell of a blaring trombone“. In Ritt’s film version, we cut from a shot panning upward on the white stadium crowd in daylight, to a shot panning down the black crowd who are celebrating that night.

The Jack Jefferson character as written by Sackler is notably more complex than the black protagonists generally seen in films up to that time. He is not a stereotype, nor is he a “pure” hero like the protagonists Sidney Poitier often portrayed. He is his own man, defying the efforts of those around him to make him representative of his race. Here, a group of black churchgoers tries to tell Jack that his victory the next day would be a victory for all blacks:

YOUNG NEGRO

Yeah – ah proud to be cullud tomorrow!

NEGROES

Amen, that’s it.

But Jack responds:

JACK

Uh huh. Well, country boy, if you ain’t there already, all the boxin’ and n*gg*r-prayin’ in the world ain’t gonna get you there –

As in the stage play, much of the screenplay’s significant action, e.g., the first championship bout, and the suicide of Jack’s wife, occurs off-stage (or off-screen). However, Sackler’s screenplay makes up for this by concluding with a big on-screen action sequence, Jack’s final championship fight in Havana, where he is defeated by (or does he deliberately lose to?) a white challenger. It ends with a memorable image, the victory parade for the challenger in the foreground (moving right to left), while Jack, his trainer, and his Jewish manager – having made their mark on history – recede “moving into the shadows” of the background.

Out of stock

Related products

-

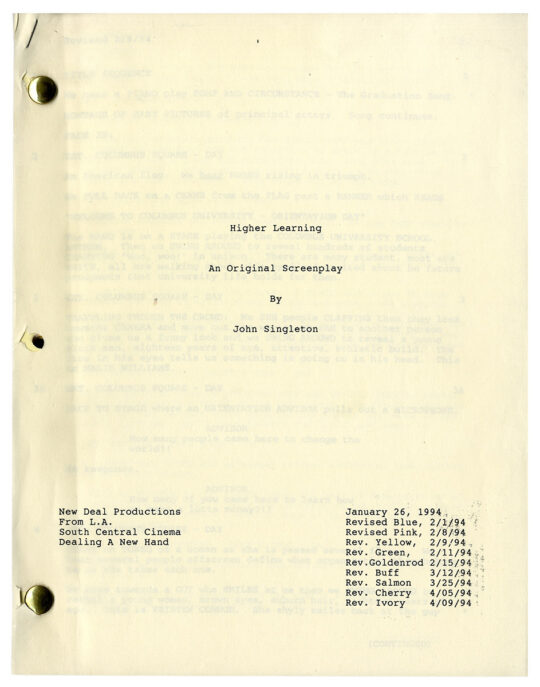

John Singleton (writer, director) HIGHER LEARNING (Jan 26, 1994) Rainbow film script

$500.00 Add to cart -

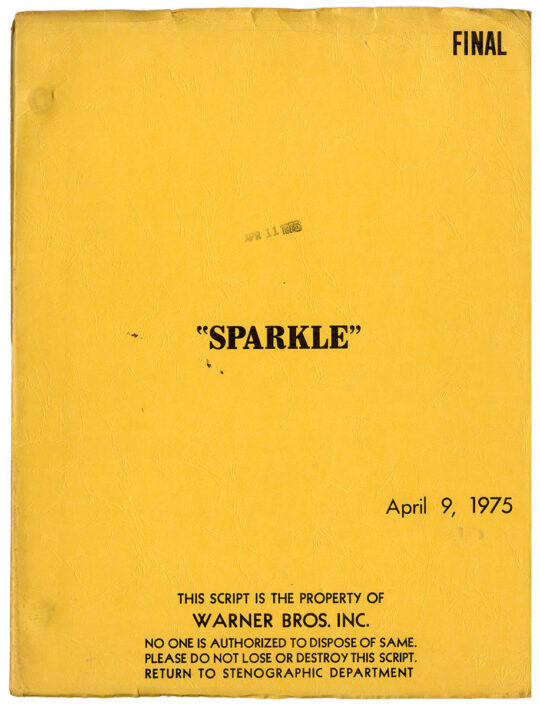

(Blaxploitation film) SPARKLE (Apr 9, 1975) Final Draft film script by Joel Schumacher

$750.00 Add to cart -

![(Blaxploitation film) BLACK BELT JONES [1974] Film script by Oscar Williams](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/BlackBeltJonesSCR_a-540x693.jpg)

(Blaxploitation film) BLACK BELT JONES [1974] Film script by Oscar Williams

$750.00 Add to cart -

![CHINATOWN [ca. 1973] Jack Nicholson's copy of early draft film script by Robert Towne](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/ChinatownSCR_a-540x693.jpg)

CHINATOWN [ca. 1973] Jack Nicholson’s copy of early draft film script by Robert Towne

$18,500.00 Add to cart