GUARD OF HONOR (1956) Final Draft screenplay by Richard Murphy dated Sep. 5, 1956

Hollywood: Columbia Pictures, 1956. Vintage original film script, USA. Printed wrappers, brad bound, 126 pp., light wear to front wrapper, blank back wrapper is not present, generally VERY GOOD+.

An unproduced script about racism in the U.S. Air Force set in Florida. This script was astonishingly advanced for its time – undoubtedly the reason why it was not eventually made.

Boston-born Richard Murphy (1912-93) was a writer, producer and director with a Hollywood film and television career spanning from 1938 to 1980. Having served as a captain in the Army Air Forces during World War II, his screenplays frequently dealt with military themes. He received Academy Award nominations for his screenplays for BOOMERANG! (Elia Kazan, 1947) and THE DESERT RATS (Robert Wise, 1953). Other significant screenplays that Murphy wrote or co-wrote include CRY OF THE CITY (Robert Siodmak, 1948), PANIC IN THE STREETS (Kazan, 1950), YOU’RE IN THE NAVY NOW (Henry Hathaway, 1951), and COMPULSION (Richard Fleischer, 1959). His directing credits include THREE STRIPES IN THE SUN (1955) and THE WACKIEST SHIP IN THE ARMY (1960), both for Columbia Pictures.

It’s likely that Murphy meant to direct his screenplay for GUARD OF HONOR (It might also have been intended as a project for someone like Fred Zinneman or Edward Dmytryk, both of whom were associated with Columbia Pictures for whom the screenplay was written). However, due to the script’s racial angle, Columbia considered it too controversial, so the movie was never produced.

The screenplay begins with “two modern jet aircraft flying directly at Camera…. The flight leader is a Negro, Major Stanley M. Willis.” We then flashback to an Army Air Force base in the South in 1943. Two airplanes nearly collide in the dark, one of them flown by young Lt. Willis, Commander of the Negro Squadron, the other flown by a white man, Col. Benny Carricker, and though the near-collision was due to a mechanical failure – neither pilot was at fault – the white officer punches the black officer in the eye.

Under ordinary circumstances an officer who strikes another officer would be court-martialed, but here the situation is complicated. For one thing, the white Colonel “Benny” is the unit’s leading combat pilot – he’s the officer in charge of training the new black pilots – and if anyone else had been flying the plane, there might have been an actual collision. For another, a couple newspapers, white and black, have gotten wind of the incident, and the Southern white newspaper editor is strongly “opposed to our program of integrating Negro troops into the Air Corps.”

The desegregation of the armed forces occurred roughly 10 years before the desegregation of the country in general. In fact, the Supreme Court’s key desegregation case, Brown vs. Board of Education, was decided in 1954, only two years before the date of this screenplay. With a few rare exceptions, Hollywood did not begin to address these issues in earnest until the late 1950s with films like EDGE OF THE CITY (1957), THE DEFIANT ONES (1958), THE WORLD, THE FLESH AND THE DEVIL, NIGHT OF THE QUARTER MOON, and ODDS AGAINST TOMORROW (1959). Richard Murphy’s 1956 screenplay for GUARD OF HONOR was literally ahead of its time.

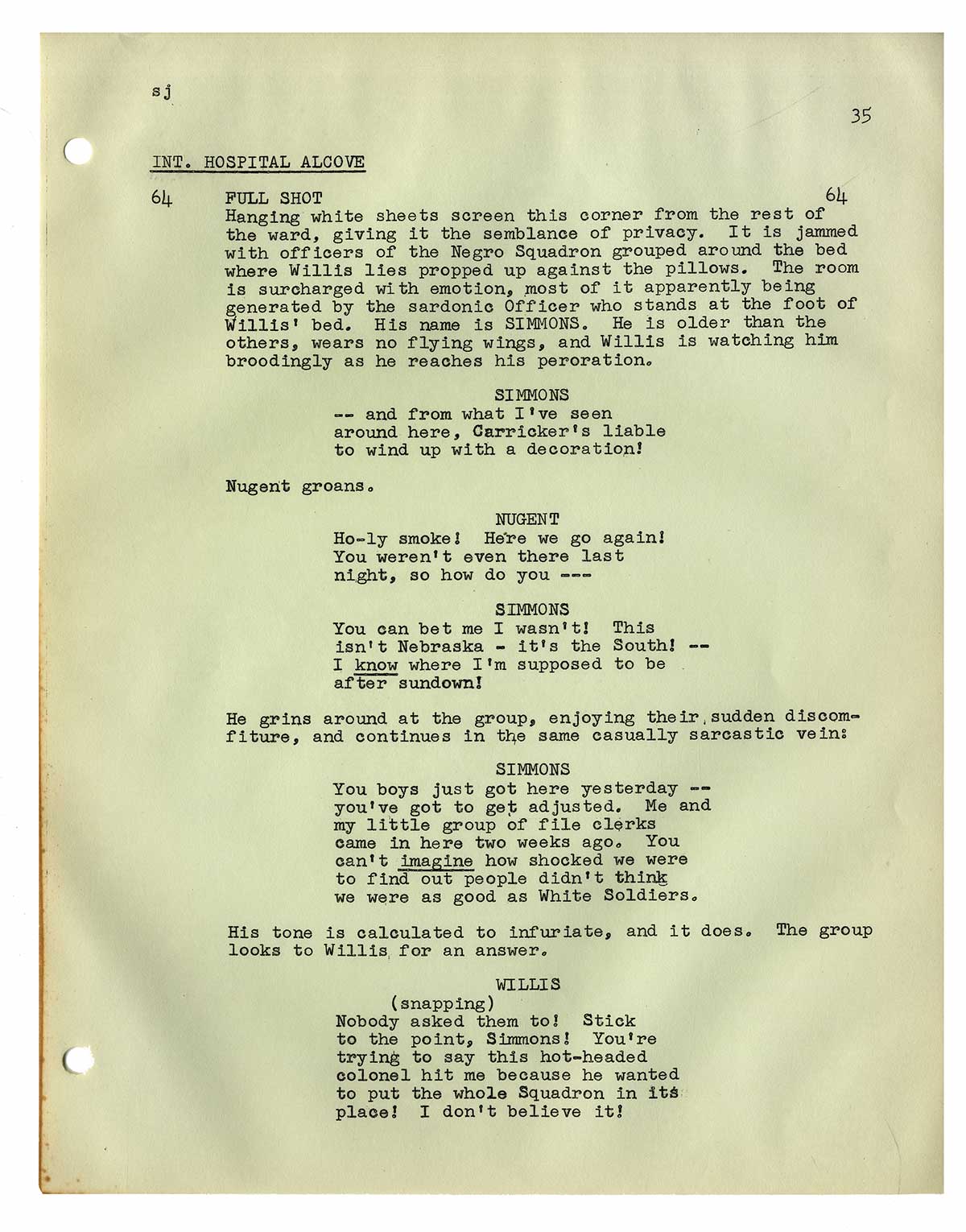

Murphy’s screenplay skillfully blends dialogue and action. Lt. Willis, the officer who was struck, does not to want to press charges, but there are others in his Negro Squadron, such as Simmons, who are more militant than he:

NUGENT

You weren’t even there last night, so how do you —

SIMMONS

You can bet me I wasn’t! This isn’t Nebraska – it’s the South! – I know where I’m supposed to be after sundown!

It is Simmons who reports the incident to the black newspaper.

In terms of action, there is a flight training exercise where Lt. Willis proves himself the equal of any white pilot – including Col. Benny. There is a desegregated officers’ dance, which breaks out into a riot. The film’s thematic resolution occurs in a dialogue sequence between Benny and a female officer, Lt. Amanda Turck, who asks him bluntly if he would have punched Lt. Willis if Willis wasn’t black, and the basically decent Benny realizes – for the first time – his own unconscious racism.

This is a thoroughly professional piece of screenwriting and probably would have been made into a fine film were it not for the particular limitations of the era when it was written.

Out of stock

Related products

-

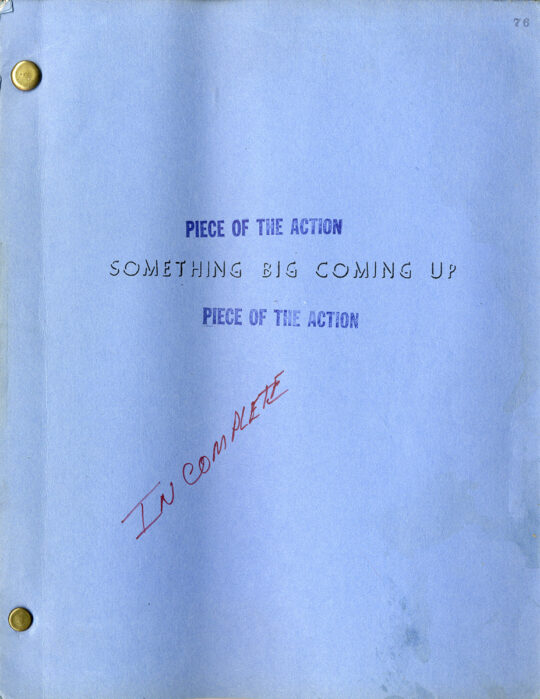

(African American film) A PIECE OF THE ACTION [working title: SOMETHING BIG COMING UP] (Nov 1, 1976) Film script

$750.00 Add to cart -

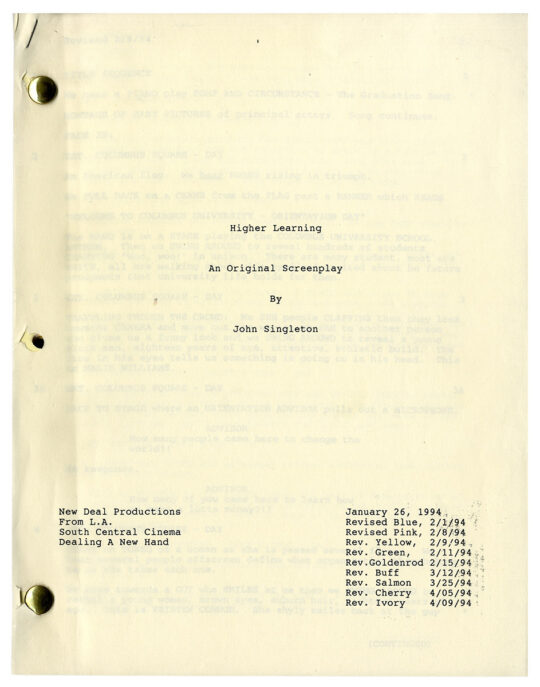

John Singleton (writer, director) HIGHER LEARNING (Jan 26, 1994) Rainbow film script

$500.00 Add to cart -

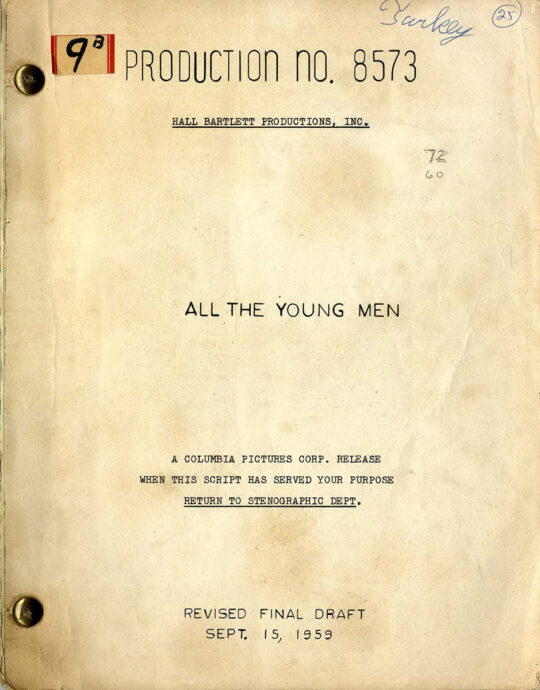

ALL THE YOUNG MEN (Sep 15, 1959) Revised Final Draft script by Hall Bartlett

$450.00 Add to cart -

SEARCHING WIND, THE (Nov 7, 1946) Final White script by Lillian Hellman

$1,500.00 Add to cart