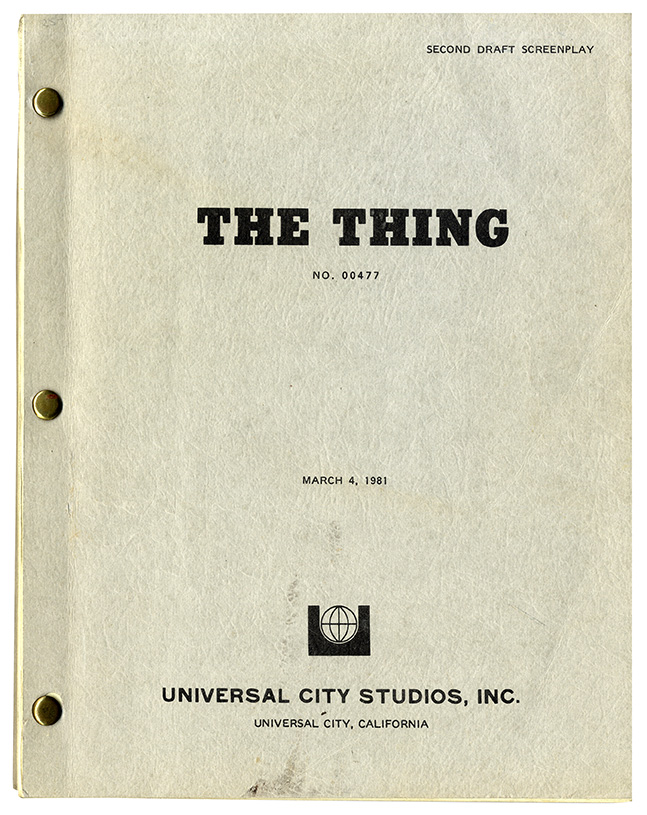

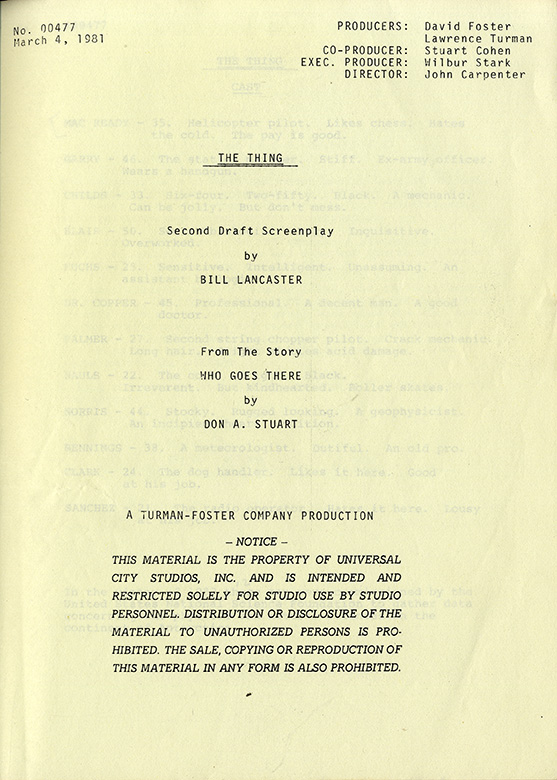

THING, THE (1982) Second Draft Screenplay by Bill Lancaster March 4, 1981 / John Carpenter (director)

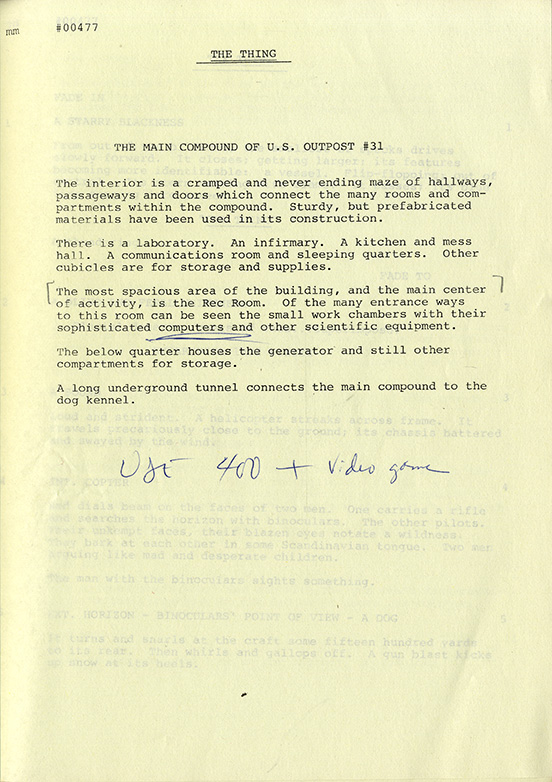

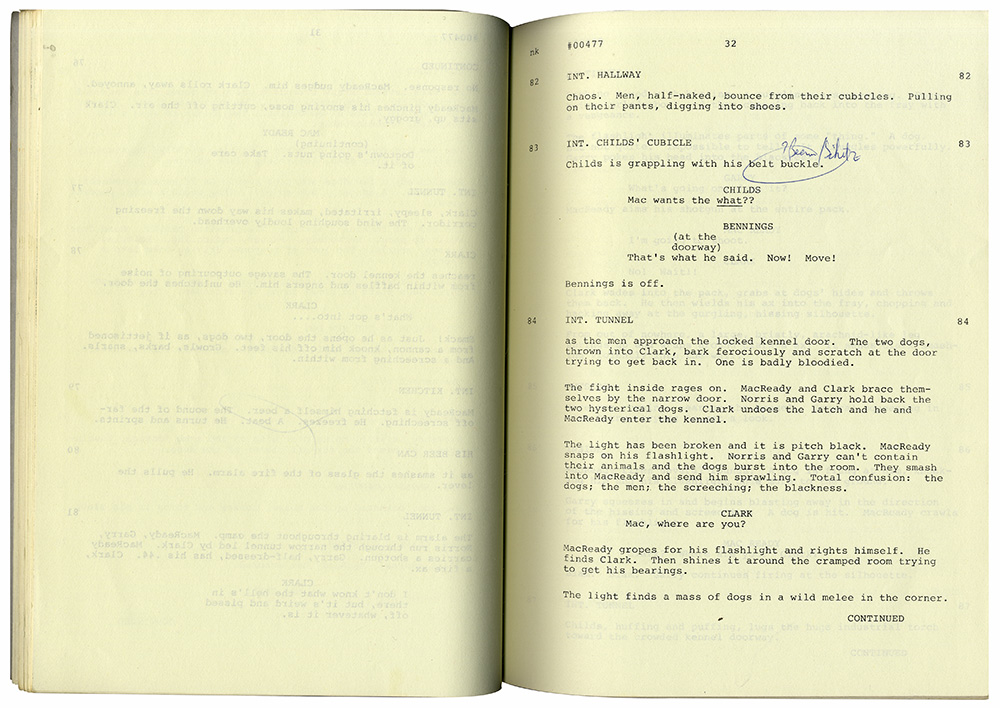

Quarto, printed wrappers, brad bound, 121 pp. There is some damage to the last five pages of text, mostly puncture marks, but also with paper loss to the last two pages. None of this wear has any effect on the text, which is entirely intact; the wrappers have a bit of smudging and wear. There are a few scattered MS notes in the hand of an unknown crewmember. Overall, VERY GOOD+.

William “Bill” Lancaster (November 17, 1947– January 4, 1997), the son of actor Burt Lancaster, was an actor and screenwriter whose best known works were his original screenplays for THE BAD NEWS BEARS film series — he received a Writers Guild of America Award for the original 1976 film — and his 1980s adaptation of John W. Campbell’s “Who Goes There?” as THE THING. While, on its face, THE THING might not seem to have much in common with THE BAD NEW BEARS, both projects are, in fact, consummate ensemble pieces.

As most horror and sci-fi fans know, the John Carpenter movie of THE THING was the second filmed version of Campbell’s story. The first version, THE THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD (1951), was produced and directed (uncredited) by Howard Hawks from a screenplay by Charles Lederer and Ben Hecht. While the Hawks/Lederer/Hecht THING is a classic in its own right, the later Lancaster/Carpenter version is far more faithful to Campbell’s 1939 text and — thanks to Lancaster’s skillful story construction, Carpenter’s inspired direction, and Rob Bottin’s incredible creature effects — has earned a reputation as one of the greatest and most terrifying “monster movies” ever made. It was released in 1982, the same year that saw the release of two other landmark sci-fi films, Ridley Scott’s BLADE RUNNER and Stephen Spielberg’s E.T. Reagan-era audiences embraced Spielberg’s loveable extraterrestrial, while at the same time rejecting the darker visions of Carpenter and Scott.

Although director Carpenter was a big fan of Howard Hawks — he even included a clip of Hawks’ THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD in his breakout film, HALLOWEEN (1978) — the Hawks influence (stories of men in groups) is eclipsed by two much more prominent influences, the visceral claustrophobic horror of Ridley Scott’s ALIEN (1979), and the cosmic sci-fi/horror blend of writer H.P. Lovecraft (who influenced not only ALIEN and THE THING, but also the original Campbell story on which THE THING was based). Take away the sci-fi elements from Lancaster’s screenplay, and you have a (fundamentally) one-set dramatic ensemble piece with affinities to such one-set classics of the American theater as Robert E. Sherwood’s THE PETRIFIED FOREST and Eugene O’Neill’s THE ICEMAN COMETH.

In THE THING, the ice is literal. It’s the story of 12 men confined to an Antarctic research camp by ice and snow. The only other significant characters are a Norwegian helicopter pilot who dies in the first scene, the camp’s dogs, and the extraterrestrial invader. The extraterrestrial’s ability to invade and take over the body of any other life form it encounters (like a disease) have caused some critics to link THE THING with other movies that reflect or anticipate the 1980s AIDS plague.

Conspicuously absent from the Lancaster/Carpenter THING is the camaraderie of Hawks’ male groups. The men in Carpenter’s film are paranoid and distrustful of one another. And justifiably so. Unlike the Hawks film, any of the men or dogs in Carpenter’s film could be the extraterrestrial in disguise.

The Hawks film is optimistic; the extraterrestrial invader (seen by some as a metaphor for communism) is defeated in the end. The Carpenter film is grimly pessimistic, ending with the camp’s last two survivors facing each other across a dying fire, surrounded by darkness, each suspecting that the other is a “thing.”

BLAIR

Can’t you see? … If one cell of this Thing got out, it could imitate every living thing on Earth. Nothing could stop it! Nothing!

There is lots of action, and the way it is described in Lancaster’s screenplay (written with input from director Carpenter) is admirably minimalist:

The lights go. MacReady charges into the black room. Blair fires. MacReady barrels into him, knocking him to the ground. He pummels him with a right hand and manages to control the gun.

The others dive in and pile on.

The completed film follows the basic structure of this draft, but the movie is more streamlined, the action cleverer, the dialogue leaner. Some profanity has been removed. The name of the radio operator has been changed from Sanchez to “Windows.” The special effects sequences are more developed and elaborate in the movie than in the screenplay, e.g., the mind-boggling moment when Norris’s head detaches itself from his transforming body and scampers away on spider legs is not described in this draft. The stark grimness of the narrative is balanced by occasional flashes of humor.

CLARK

I don’t know what the hell’s in there, but it’s weird and pissed off . . . .

A scene in which some of the men chase infected dogs out into the snow was scripted, but never shot. And Carpenter apparently shot (and audience-tested) more than one version of the downbeat ending. Interestingly, one of the movie’s most effective set pieces, the suspenseful blood testing sequence (not in the Hawks version) comes straight out of Campbell’s original story.

Lancaster’s screenplay is thoroughly professional and highly readable — a model of its kind. This particular copy was evidently owned by someone in the production’s prop department, with significant props (snowmobile, computer, tape recorder, dog food, magazines) circled or underlined when they appear.

Out of stock

Related products

-

(Jewish American film) THE CHOSEN (Jul 25, 1980) Film script

$400.00 Add to cart -

Mark Twain (source) LIFE ON THE MISSISSIPPI (ca. 1956) TV script adapted by William Robert Yates

$300.00 Add to cart -

SLEEP ON THE ROOF (1967) Unproduced script based on the life of Margaret Sanger

$500.00 Add to cart -

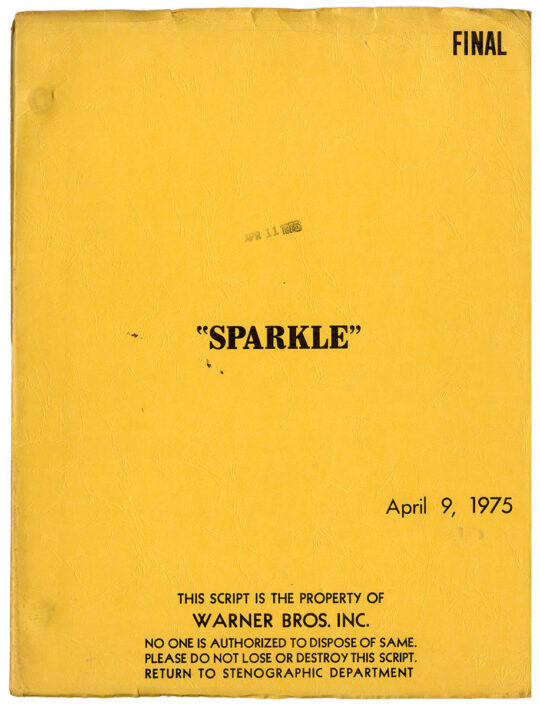

(Blaxploitation film) SPARKLE (Apr 9, 1975) Final Draft film script by Joel Schumacher

$750.00 Add to cart