John le Carré (source) THE SPY WHO CAME IN FROM THE COLD (Nov 16, 1964) First final UK film script by Paul Dehn

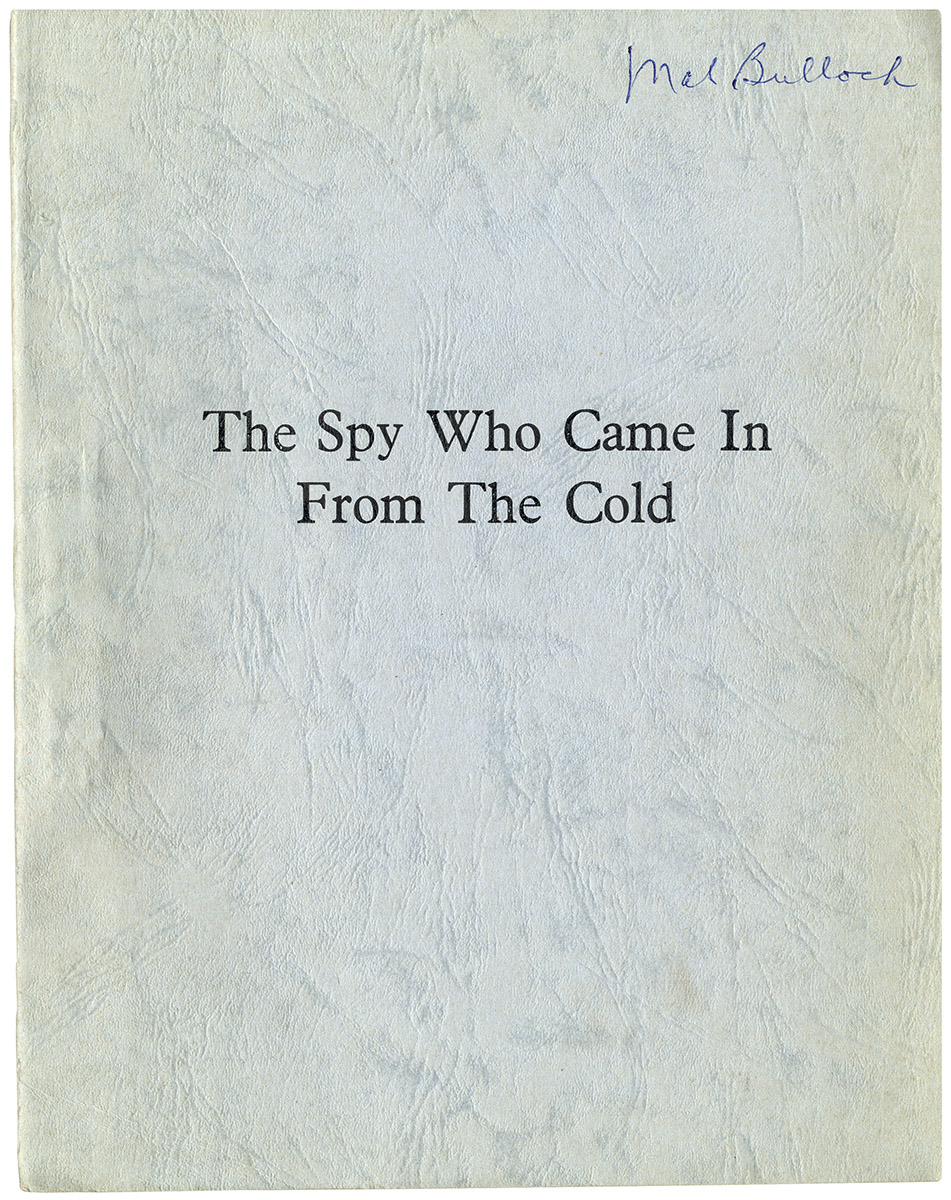

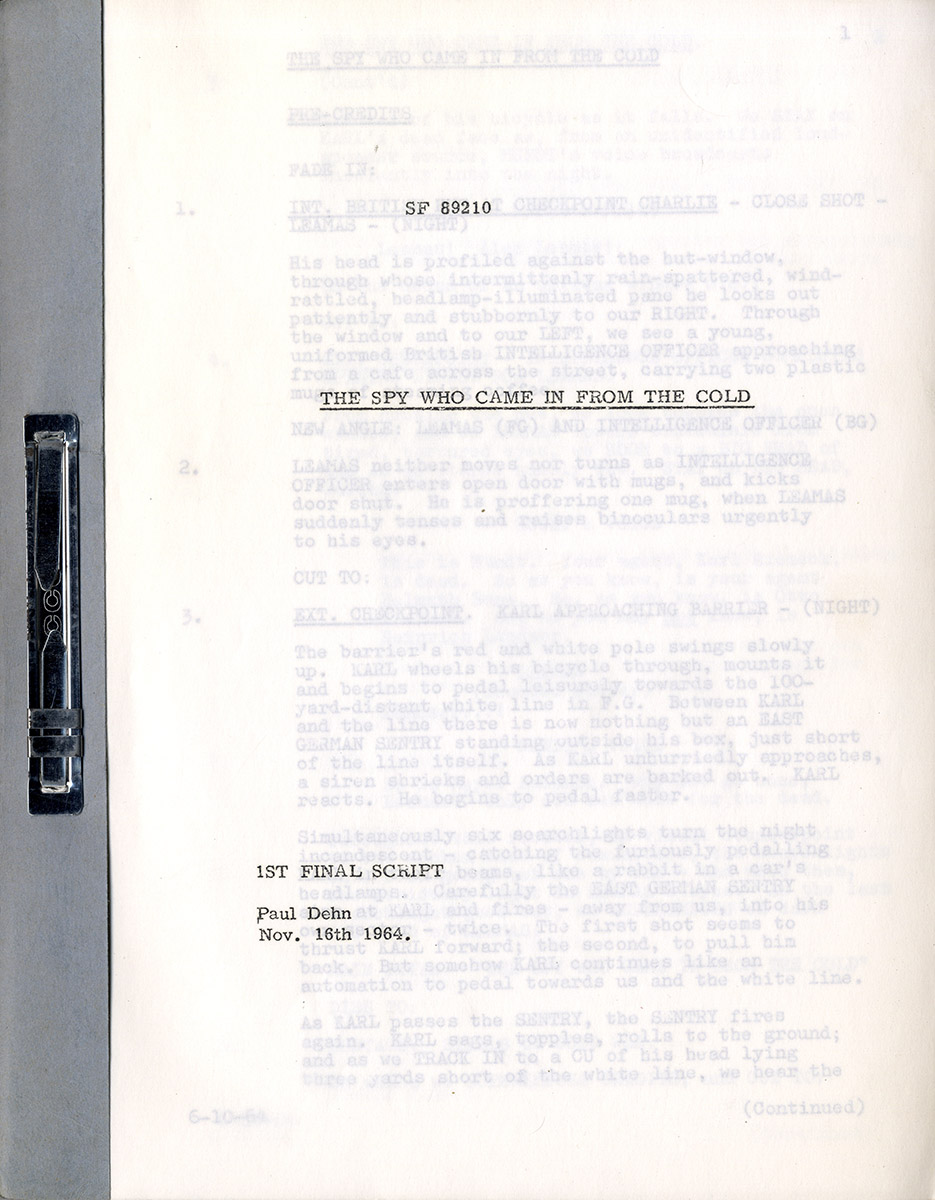

[London]: 1964. Vintage original film script, 11 x 8 1/2″ (28 x 22 cm.), 144 pp., mimeograph, printed wrappers, bound internally with a metal clasp. A name written on front wrapper, three actors’ names written on inner front wrapper. Noted as 1st Final Script, written by Paul Dehn and dated Nov. 16th, 1964. In a clamshell box, just about fine.

Martin Ritt produced and directed The Spy Who Came in From the Cold immediately after his greatest critical and popular success, the Paul Newman vehicle Hud (1963), a movie that was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won three (for Best Actress, Best Supporting Actor, and Best Black-and-White Cinematography). Of even more significance, historically speaking, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold was a spy movie released when the James Bond craze was at its peak, following the international success of Dr. No (1962), From Russia With Love (1963) and Goldfinger (1964).

Where the James Bond spy movies were glamorous and colorful, full of sex, violence, action, high-tech gadgetry and exotic locales, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold was the exact opposite. Based on a novel by John le Carré, it was intentionally anti-glamorous, drab and bleak, had no gadgetry, very little sex, almost no action to speak of, and presented espionage as a grim and depressing way of life.

This “1st Final Script” of The Spy Who Came in From the Cold was written by Paul Dehn, a British screenwriter best known, ironically enough, for co-scripting Goldfinger, as well as co-writing the Academy Award-winning story of Seven Days to Noon (1950), an English suspense thriller, and later for scripting Sidney Lumet’s Murder on the Orient Express (1974). Dehn had previously worked in the Special Operations Executive as an assassin during World War II! On screen, the screenplay of The Spy Who Came in From the Cold is co-credited to Dehn and Guy Trosper, an American screenwriter who had worked on John Frankenheimer’s Birdman of Alcatraz and Marlon Brando’s One- Eyed Jacks. Since the movie follows Dehn’s “1st Final Script” quite closely, one can assume that Guy Trosper was the author of an earlier draft.

The screenplay of this convoluted Cold War thriller begins with our protagonist, Alec Leamus (Richard Burton), witnessing the shooting of a German, secretly a British agent, who is attempting to escape from East Berlin. Agent Leamus is then ordered by his superior, “Control”, to go undercover himself as a defector. First, he is apparently fired by the Agency. Masquerading as a drunken lout with little or no money, he obtains employment in a psychic book shop.

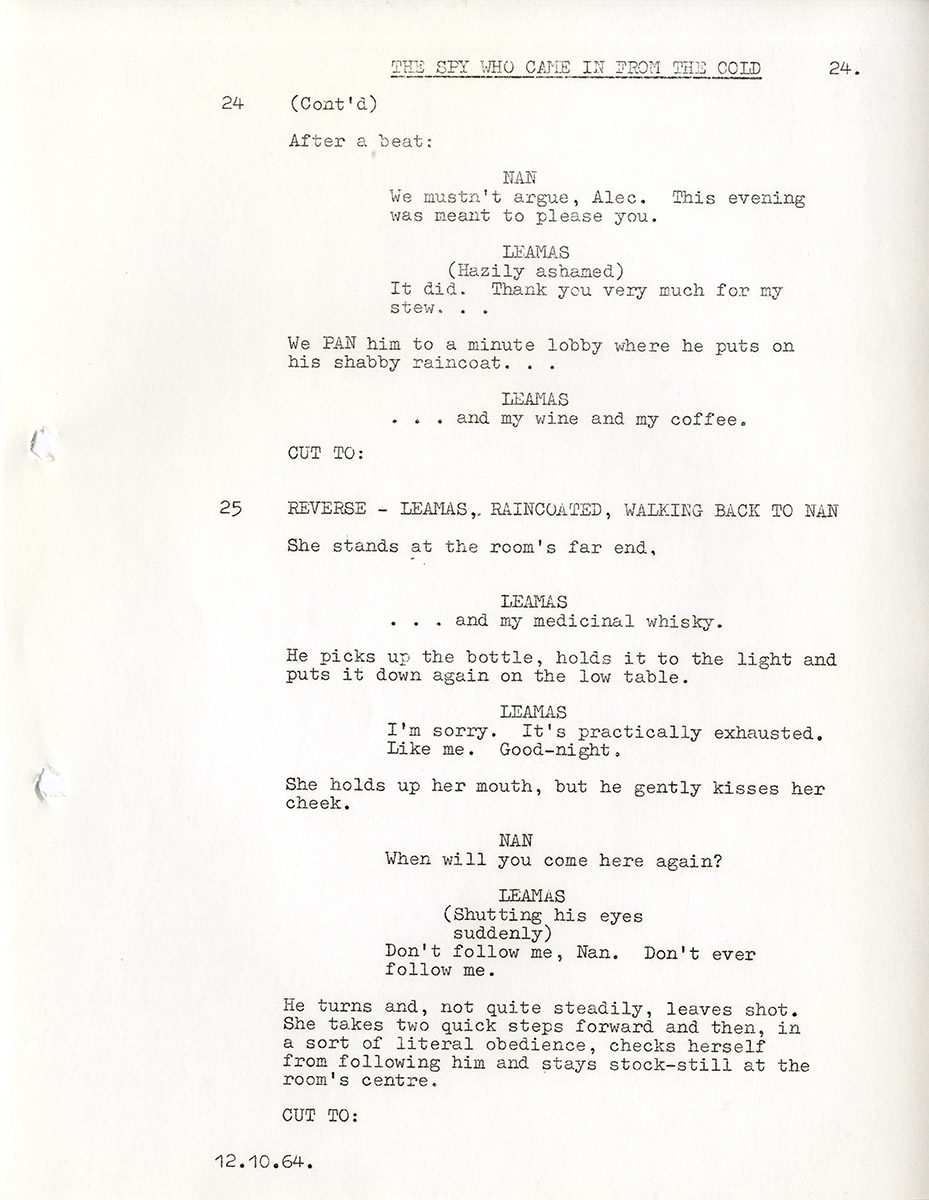

There he meets Nan (Claire Bloom), another employee (a communist!) with whom he begins an affair. A brawl with a shopkeeper lands him in prison. When he emerges, he is recruited by East German agents, offering to pay him for what he knows. The apparent purpose of all this is to pass on evidence that will incriminate a German agent named Mundt (Peter van Eyck).

Leamus’ main interrogator is a German Jew named Fiedler (Oskar Werner). However, the Germans use Nan to discredit Leamus’ testimony. This results in Mundt getting cleared and Fiedler getting shot, which was the Agency’s hidden purpose all along since Mundt was, in fact, secretly working for the English. The story ends on a downbeat note with Leamus and Nan getting shot while attempting to scale the Berlin Wall.

The style of Dehn’s screenplay is very much like its subject matter — very professional, very detailed, very British — and, apart from some trimmed dialogue and a few omitted scenes, the movie is impeccably faithful to it. One omitted sequence has Nan meeting with le Carré’s most famous character, George Smiley. In another omitted scene, Leamus kills an East German guard. Dehn’s dialogue is a perfect match for Richard Burton’s dry, sardonic delivery of it.

Director Martin Ritt was essentially a realist, and his black-and-white deglamorization of the spy business echoes his deglamorization of the American West in Hud.

Burton in The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, like Paul Newman in Hud, is an attractive and charismatic actor cast in a fundamentally unsympathetic role. The Spy’s concern with treachery and the naming of names (identification of agents) anticipates Ritt’s treatment of the McCarthy Era in The Front (1976).

Born David John Moore Cornwell, John le Carré (October 19, 1931 – December 12, 2020) was best known for being an ex-MI6 agent turned novelist. The Spy Who Came in From the Cold was the first of his Cold War spy novels to be adapted to the movie or television screen. Subsequent adaptations included The Looking Glass War (1965), Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974), Smiley’s People (1979), The Little Drummer Girl (1983), The Night Manager (1993), The Tailor of Panama (1996), The Constant Gardener (2001), A Most Wanted Man (2008) and Our Kind of Traitor (2010).

This film is often cited as an example of neo-noir. Grant, pp. 603-4.

Out of stock

Related products

-

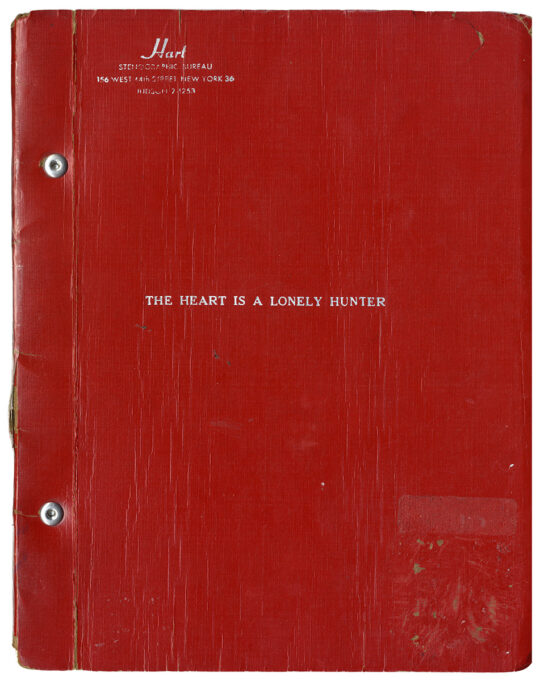

Carson McCullers (source) THE HEART IS A LONELY HUNTER (Aug 26, 1963) Film script by Thomas C. Ryan

$1,000.00 Add to cart -

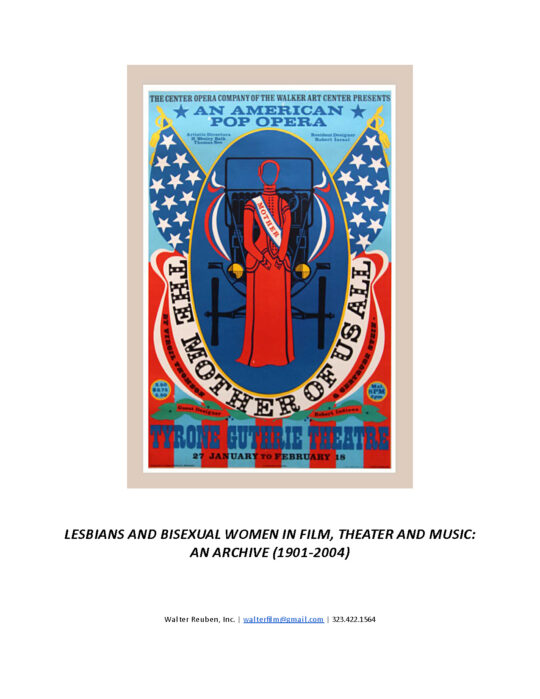

LESBIANS AND BISEXUAL WOMEN IN FILM, THEATER & MUSIC (1901-2004) Archive

$40,000.00 Add to cart -

SEARCHING WIND, THE (Nov 7, 1946) Final White script by Lillian Hellman

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

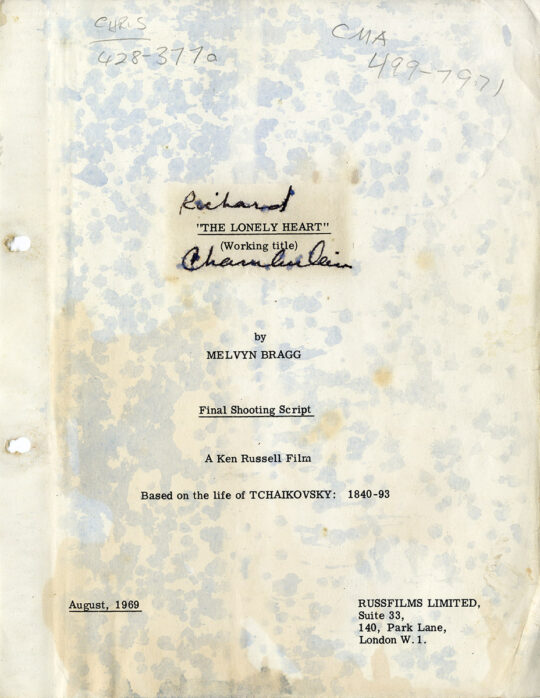

Ken Russell (director) THE MUSIC LOVERS [working title: THE LONELY HEART] (1969) Final shooting script

$3,000.00 Add to cart