PRIVATE FILES OF J. EDGAR HOOVER, THE (ca. 1973-75) Script archive

[Los Angeles, ca. 1973-75]. Set of two (2) vintage original film scripts, quarto, about 11 x 8″ (28 x 20 cm.).

Larry Cohen (1936-2019) was an extraordinarily prolific and inventive filmmaker, who wrote or co-wrote the screenplays for more than forty feature films and directed 19 of them. He was most associated with the horror or “monster” genre, his most important films being It’s Alive (1974), God Told Me To (1976), It Lives Again (1978), Q—The Winged Serpent (1982) and A Return to Salem’s Lot (1987). In The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover (1977), Cohen analyzes a real-life monster.

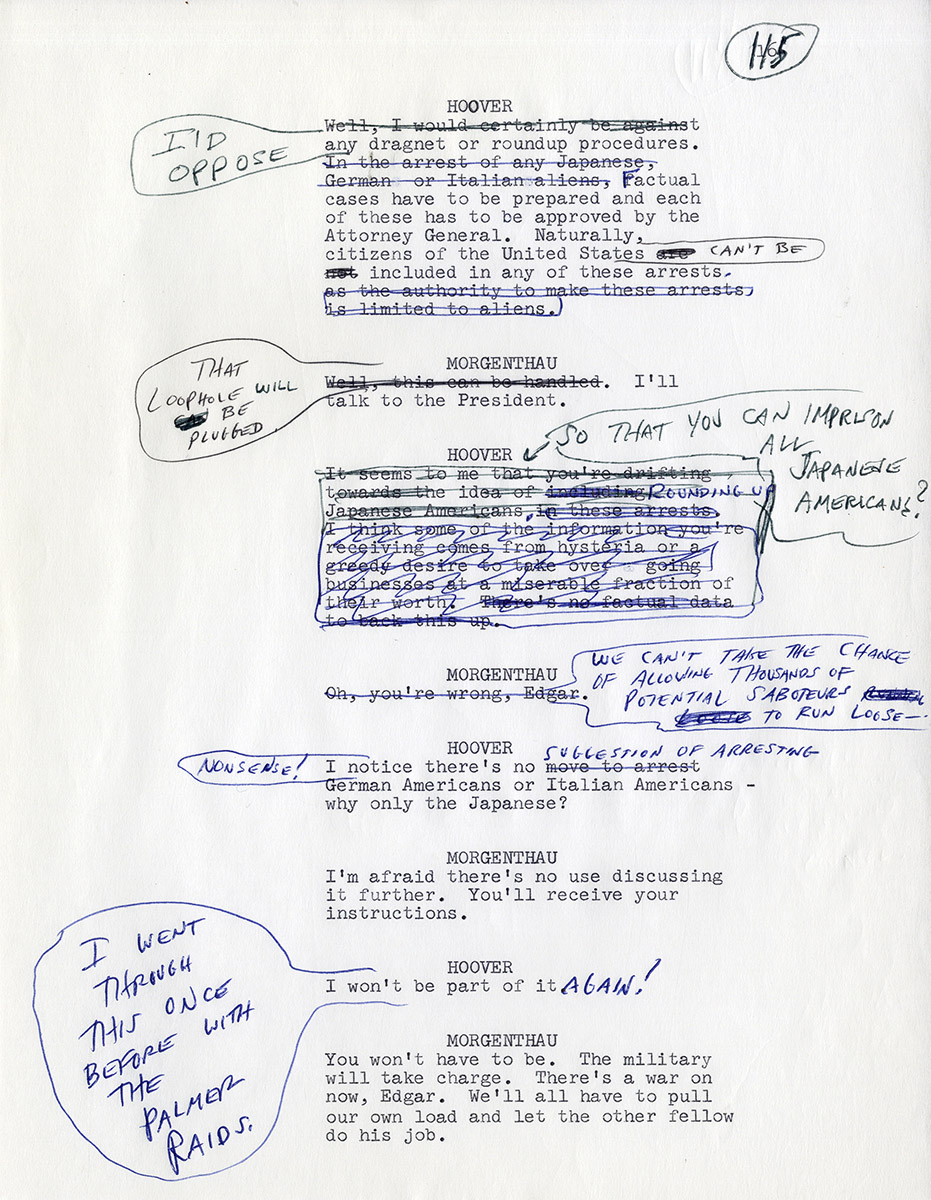

— J. EDGAR HOOVER (ca. 1973) Typescript Heavily revised, with a few hundred annotations in ink in Cohen’s hand. Unbound, about 245 pp., near fine.

J. Edgar Hoover is the first draft of what would eventually become Larry Cohen’s The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover. It is copiously annotated and corrected by the writer/director. The later draft of March 12, 1975, titled The Secret Files of J. Edgar Hoover, is essentially an edited version of this “original manuscript” with Cohen’s handwritten dialogue and other material retyped into readable form.

However, Cohen’s original manuscript is also substantially longer and contains significantly more dialogue than the March 1975 draft, much of it crossed out but still readable (in case the writer changed his mind and wanted to reinsert it). Much of the principal interest of the original manuscript — aside from seeing so much of the film’s dialogue and scene descriptions handwritten by Cohen — is noticing all the tweaks, corrections, and omissions that occurred between this manuscript and the March 1975 draft.

Many scenes and sequences were eliminated entirely. This initial draft begins, like Welles’ Citizen Kane, with a parade of witnesses and testimonials: real-life columnist Art Buchwald telling the camera “J. Edgar Hoover doesn’t exist”; then an American Legionnaire proclaiming “Today, we have lost our greatest bulwark against communism”; followed by a retired agent stating “He never really changed, you know. Never had girlfriends even back then.”

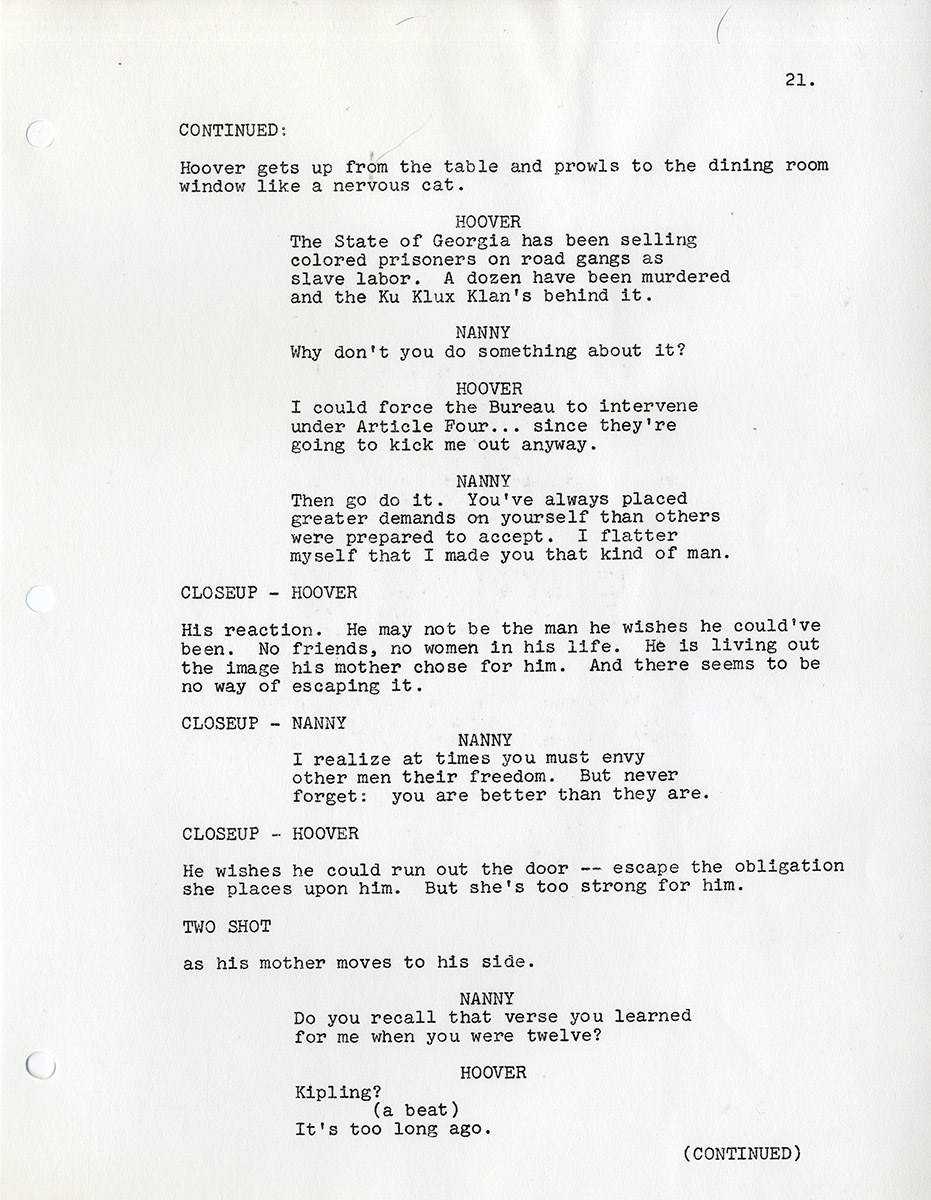

Which sets us up for the extended flashback to Hoover’s life that makes up the remainder of the film, starting with a scene of Hoover as a young cadet in military school (not in the movie), followed by a scene of 24-year-old attorney Hoover in a Washington, D.C., meeting with Attorney General Palmer as the latter plans the infamous “Palmer raids” in which communists and other suspected radicals were arrested en masse. We are introduced to the women in Hoover’s life — his doting mother Nanny and first potential girlfriend Carrie Dewitt. The relationship with Carrie goes nowhere because paranoid Hoover believes he is being set up.

Hoover’s “boy scout” reputation is what eventually gets him appointed as head of the fledgling Federal Bureau of Investigation — following the corruption of the Harding Administration — and the Bureau’s interaction with the bootleggers and gangsters of the 1930s is what propels him to national prominence. That, and a carefully orchestrated multi-media public relations effort on Hoover’s behalf that becomes one of the screenplay’s principal themes.

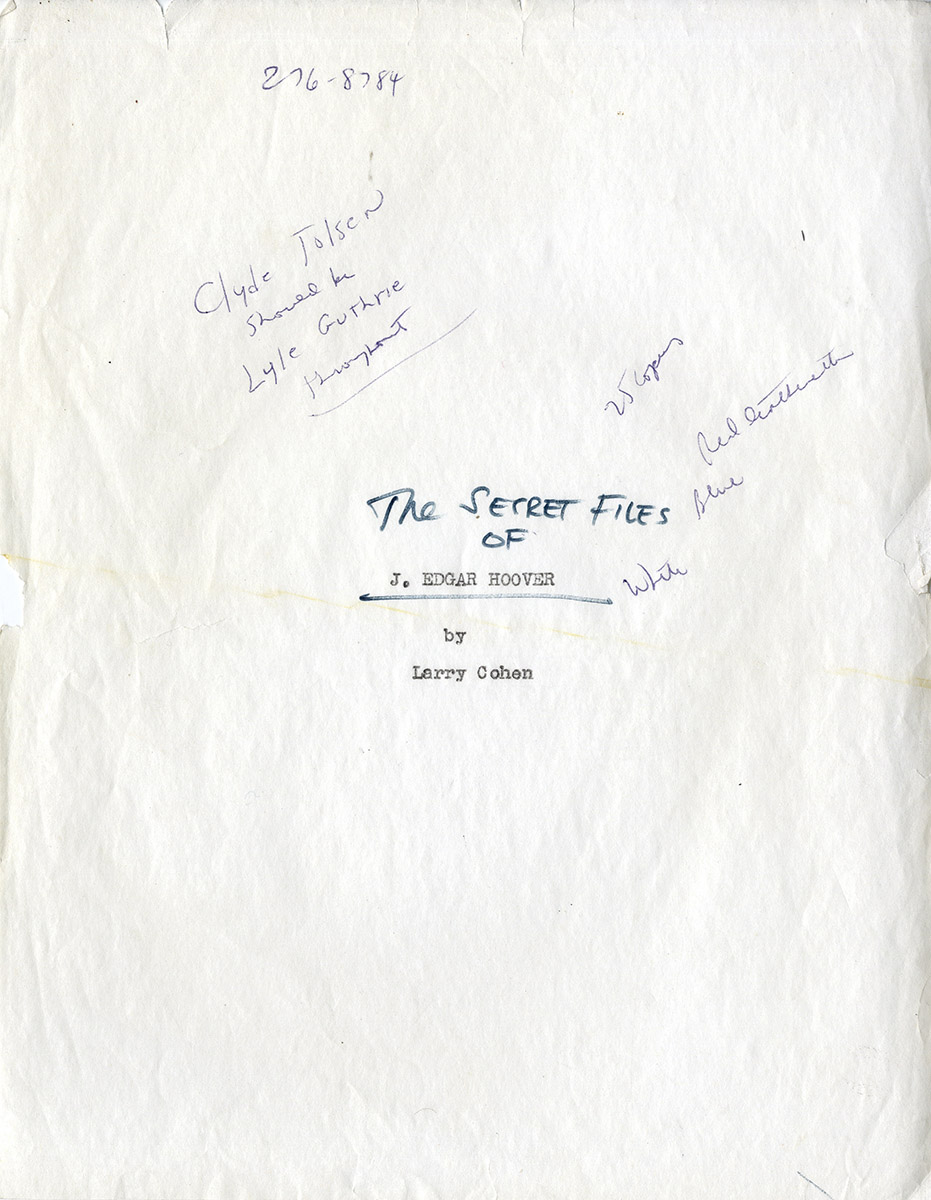

In the movie, Hoover would be played by a perfectly cast Broderick Crawford, and his long-time associate, Clyde Tolson, by Dan Dailey. The death of Hoover’s mother leads to an intriguing scene, not included in the movie, with Hoover and Tolson standing over Hoover’s mother’s grave, suggesting that Tolson has, in fact, taken her place in Hoover’s life. In another narrative thread, we see Hoover interacting with the various presidents under whom he served. We see FDR giving Hoover permission — pointedly not in writing — to conduct surveillance on Nazis, communists and other suspected subversives. In another scene, omitted from subsequent drafts, Hoover clashes with President Truman over Truman’s formation of the rival Central Intelligence Agency. Hoover’s greatest clash will be with Attorney General Robert Kennedy (played brilliantly by Michael Parks), in some ways Hoover’s doppelganger, a threat to Hoover’s power that ends when Robert’s brother John is assassinated. Hoover dies during the Nixon administration, but Cohen’s screenplay suggests it was Hoover’s secret files that finally brought Nixon down in conjunction with the Watergate scandal, and that Clyde Tolson was the “Deep Throat” who delivered the damaging information contained in those files to the Washington Post.

Hoover emerges as a monster of repression, admired, detested and pitied in equal measure by screenwriter Cohen. The movie that eventually resulted from it may be one of the finest political movies of the 1970s, but one can only regret that Cohen did not have the time and budget to make the four-hour epic he envisioned in this initial draft.

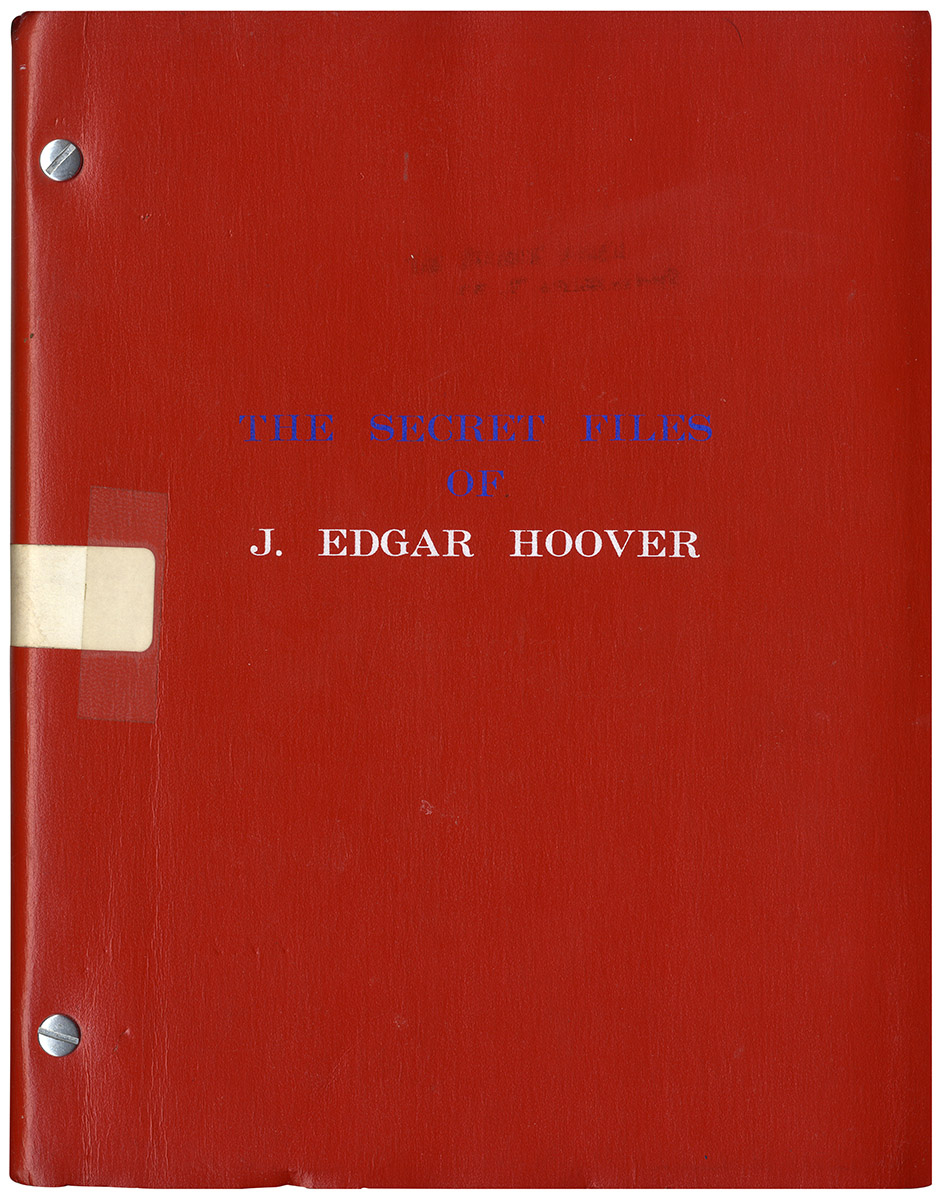

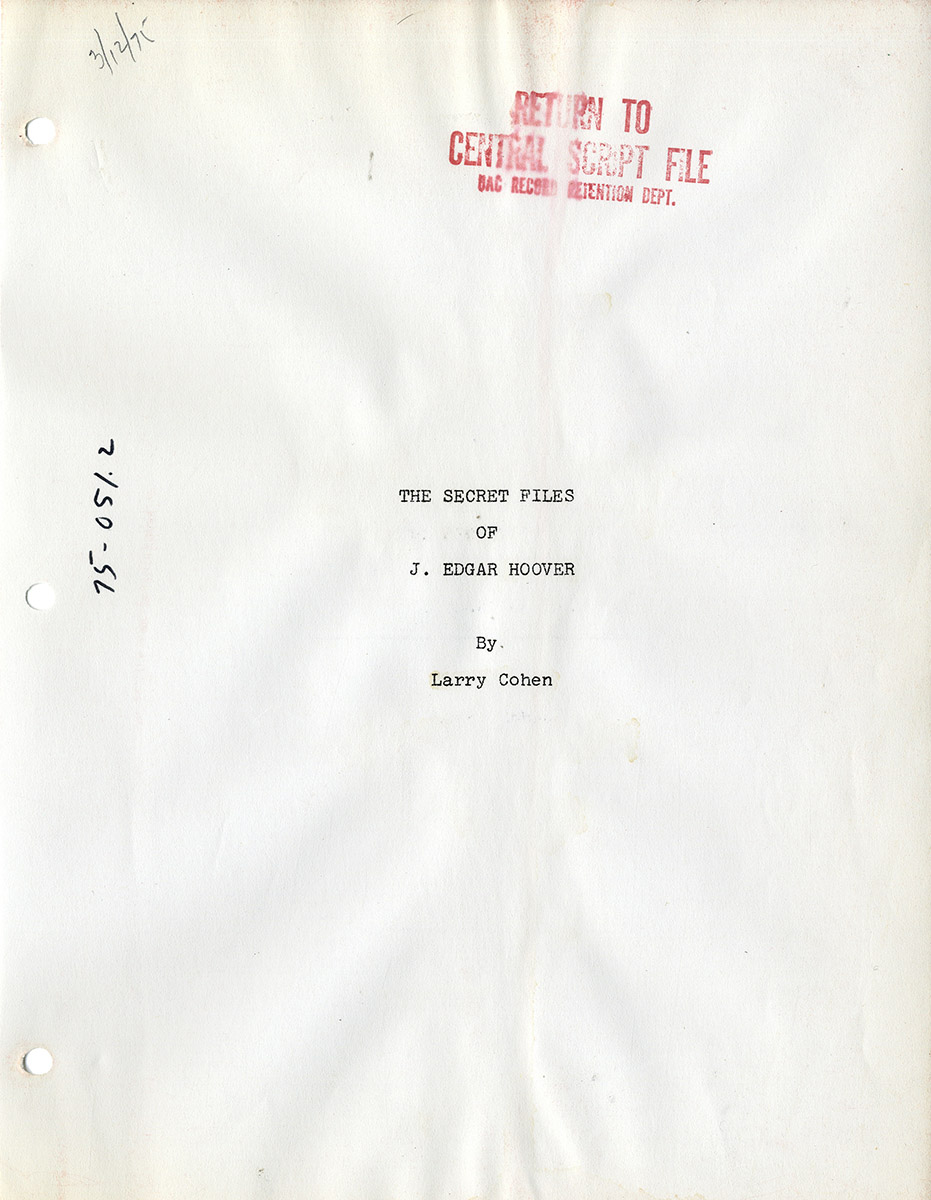

— THE SECRET FILES OF J. EDGAR HOOVER (Mar 12, 1975) Film script Stenciled vinyl wrappers, brad bound, 166 pp. A holograph note on the title page dates this script from 3/12/1975. Near fine.

Film theorist Robin Wood called Larry Cohen’s The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover “perhaps the most intelligent film about politics ever to come out of Hollywood.”

Cohen’s March 1975 screenplay draft, much shorter than the initial draft, is a preliminary version of what he eventually filmed. The completed movie’s structure is substantially the same but the dialogue has been tweaked and improved, and there were obviously some adjustments that had to be made to accommodate budget and the availability of locations. Some sequences were added and others were deleted, e.g. a scene concerning the Lindbergh kidnapping and a subplot involving a Nazi German saboteur.

Crammed with historical detail, mixing stock footage with recreated scenes shot on the actual locations where they occurred, Cohen’s Hoover foreshadows the formal strategies employed by Oliver Stone in his historical/political films JFK and Nixon. Like Stone with Nixon and Welles with Citizen Kane, Cohen revels in the contradictions of his central character. We see Hoover’s good side — how when foreign-born “radicals” were imprisoned and deported during the 1920s Palmer raids, Hoover insisted on the prisoners’ constitutional rights; how he resisted in the 1940s when President Franklin Roosevelt and California Attorney General Earl Warren wanted to confiscate the property of Japanese Americans and place them in internment camps. And we see Hoover’s dark side — his bullying, blackmailing and obsessive surveillance of everyone and everything, and his ultra-puritanical attitude toward sex. Hoover’s sexuality, such as it is, expresses itself mainly through voyeurism, through listening in on tape recordings of the sexual activities of others.

An uncompromising look at 20th century America’s political history, The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover was the most ambitious project that writer/director Cohen ever attempted and, clearly, his masterpiece.

Out of stock

Related products

-

(Jewish American film) THE CHOSEN (Jul 25, 1980) Film script

$400.00 Add to cart -

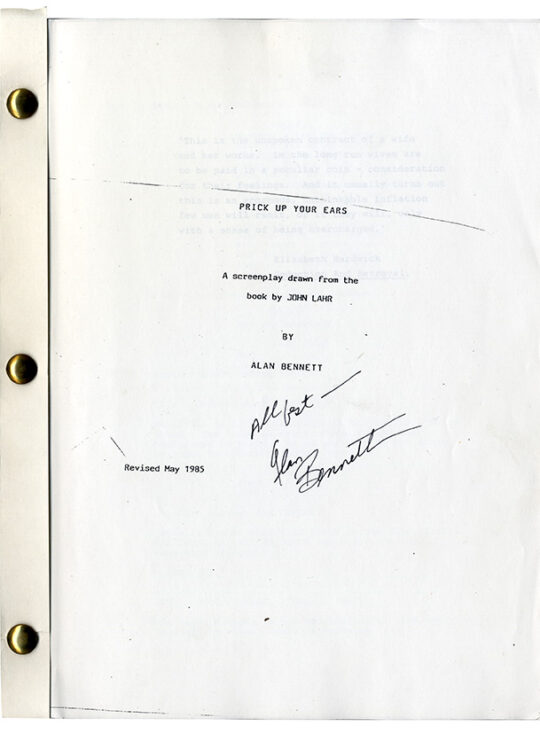

PRICK UP YOUR EARS (May 1985) Revised film script

$650.00 Add to cart -

LONG WALK HOME, THE (Oct 13, 1988) Second draft film script by John Cork

$375.00 Add to cart -

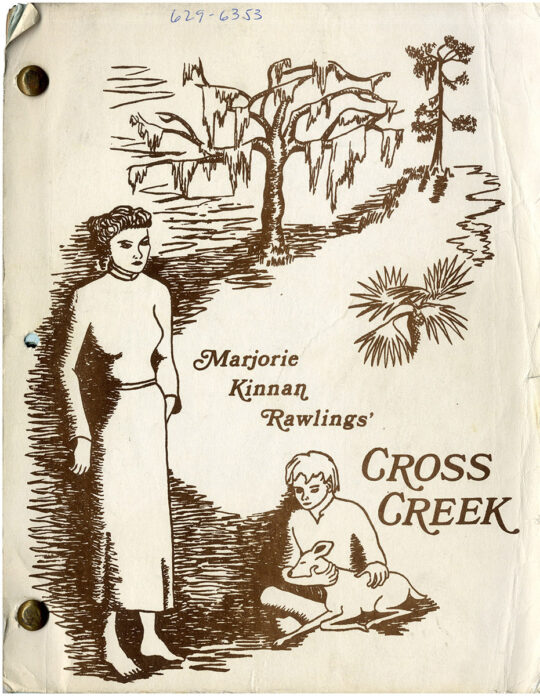

CROSS CREEK (Feb 9, 1982) Rev Final Shooting script by Dalene Young

$750.00 Add to cart