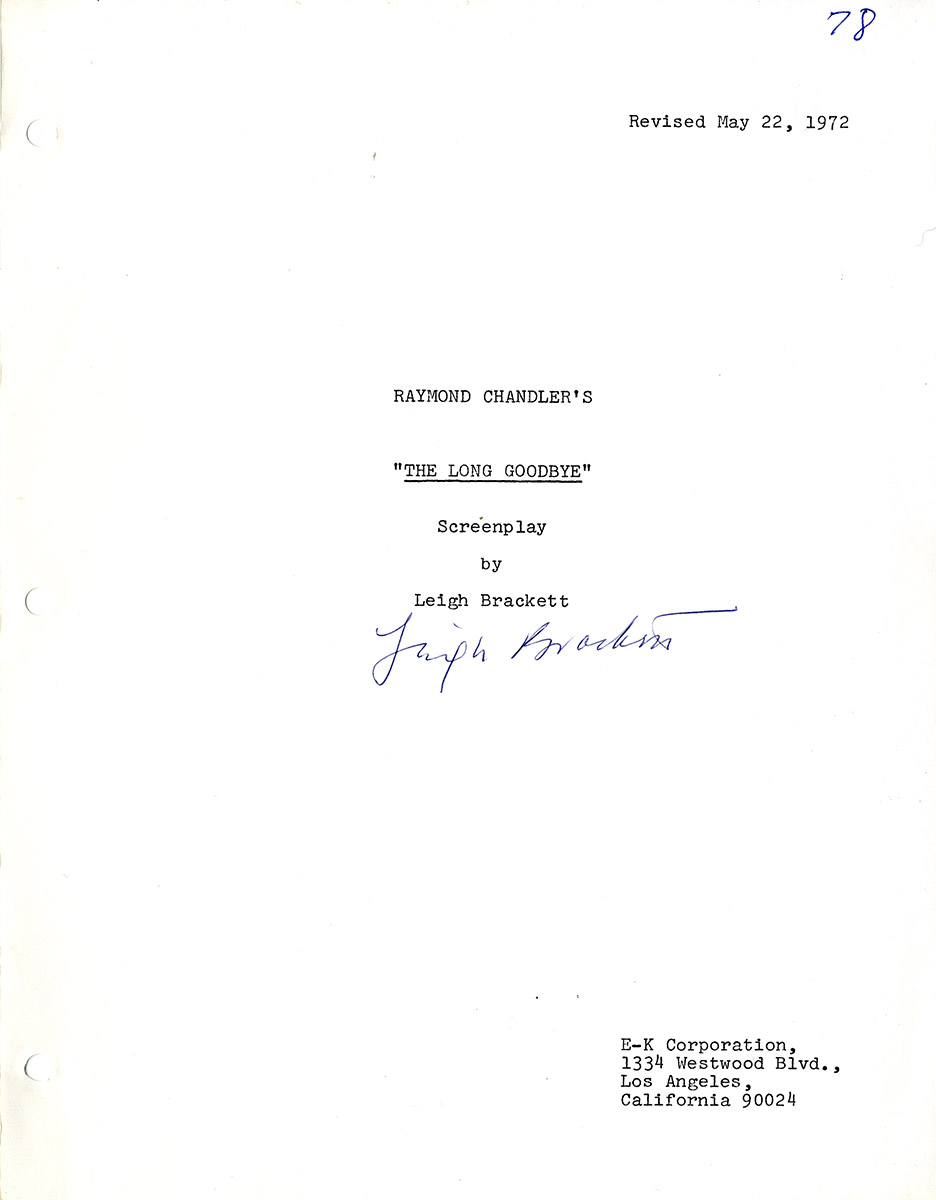

Raymond Chandler (source), Robert Altman (director) THE LONG GOODBYE (May 22, 1972) Signed revised draft film script

Los Angeles: E-K Corporation, 1972. Vintage original film screenplay, 11 x 8 1/2″ (28 x 22 cm.), printed wrappers, brad bound, mimeograph, with many pages of revisions on colored paper. Near fine or better, signed by screenwriter Leigh Brackett on title page which indicates it is a revised draft dated May 22, 1972.

The Long Goodbye, an adaptation of the 1953 private eye novel by Raymond Chandler, is a brilliantly written screenplay by one of the all-time great screenwriters, Leigh Brackett (1915-1978), an authoress whose other screen credits include The Big Sleep (another Chandler adaptation), Rio Bravo, El Dorado and The Empire Strikes Back.

Released in 1973, The Long Goodbye was the eighth feature film directed by Robert Altman, a filmmaker praised then and now as a master of genre deconstruction. Here, Altman is deconstructing the private eye genre. However, much of what film buffs admire about The Long Goodbye can be found, at least in blueprint form, in Ms. Brackett’s screenplay which was initially drafted before Altman became attached to the project.

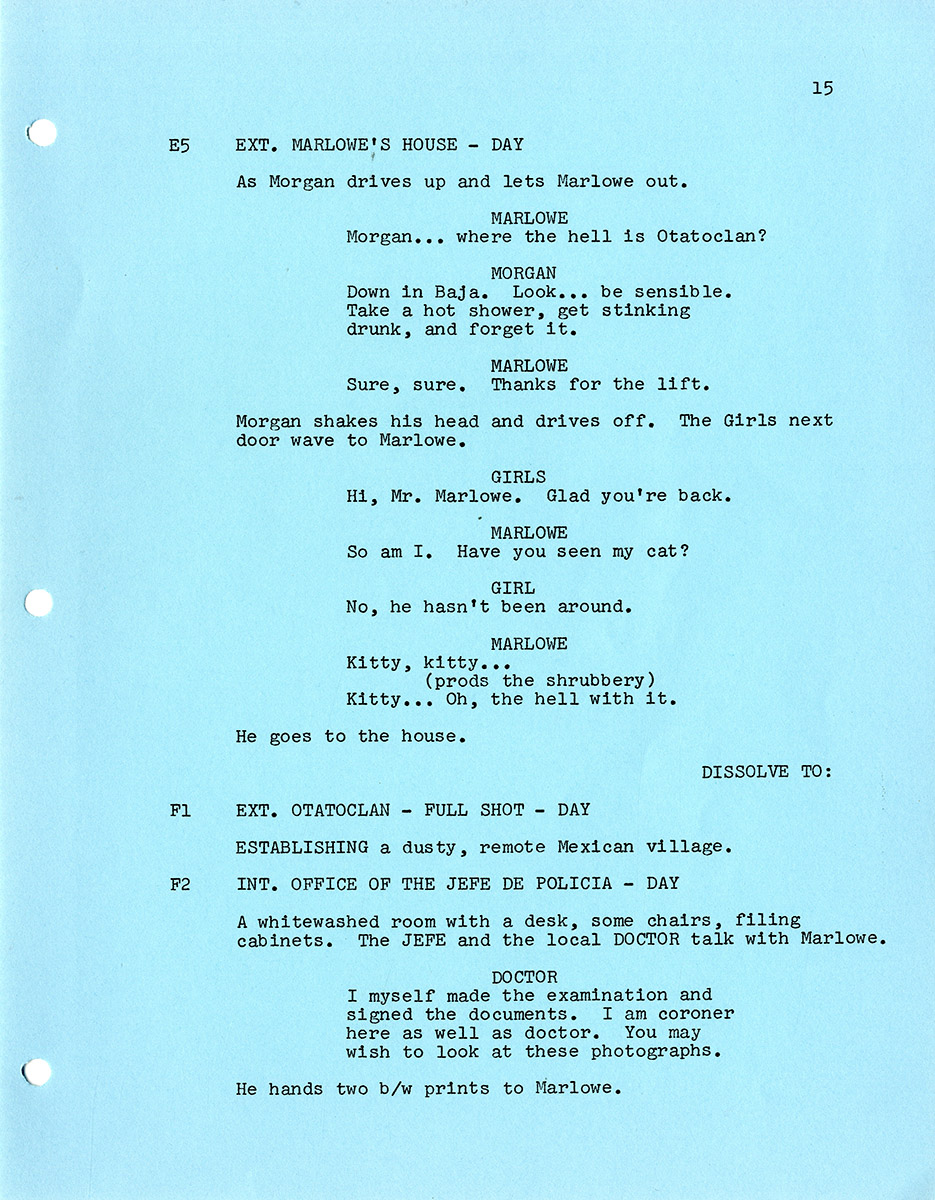

Brackett’s biggest contributions, insofar as they depart from Chandler’s novel, are the screenplay’s beginning and its end. The screenplay begins with private investigator Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould) reclining in bed, awakened by his cat who wants to be fed. Searching for a cat food that Marlowe’s cat will like well enough to eat is the story’s first innovative beat; and the loss of Marlowe’s finicky cat becomes a metaphor for all the losses and betrayals that will occur throughout the course of the tale.

The Brackett screenplay’s ending, in which Marlowe shoots the homicidal “best friend” who has used, deceived, and betrayed him, was an even more radical departure from Chandler’s novel. Altman claimed Brackett’s ending was the primary factor that convinced him to direct the movie, and stipulated in his contract with the studio that they would not be allowed to change it.

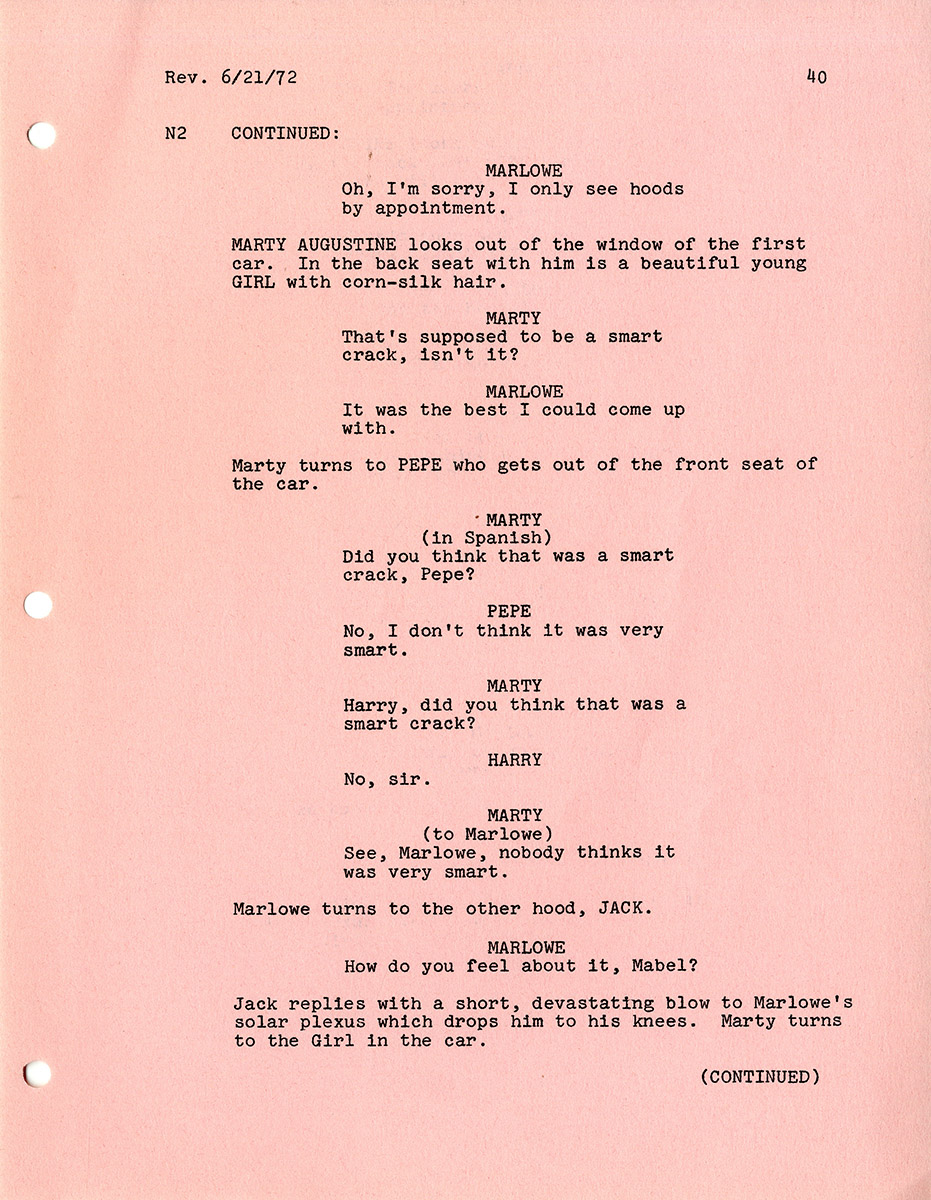

The character of Marty Augustine (Mark Rydell), the affluent Jewish gangster who, in the screenplay’s most shocking act of violence, smashes his girlfriend’s face with a coke bottle, is another Brackett invention. The endless variations on the theme song “The Long Goodbye” which are heard throughout the movie, both on its soundtrack and from sources within the film (even a doorbell!) — that, too, is in Brackett’s screenplay.

Nevertheless, since The Long Goodbye is a Robert Altman film, much of what is in the screenplay was revised or elaborated upon during the course of shooting. Taking a cue from Brackett’s script notation that Marlowe “talks to himself all the time,” Altman gave his star, Elliott Gould, a free hand to improvise throughout the production. Marlowe’s recurring catchphrase “It’s okay with me” was a Gould improvisation. The scene in the police station where Marlowe smears fingerprint ink on his face and imitates Al Jolson singing “Swanee” was another Gould improvisation. The rest of the cast, particularly Sterling Hayden as alcoholic writer Roger Wade, were also permitted to ad-lib, with equally impressive results. In the screenplay, Wade commits suicide by shooting himself, but in the movie — perhaps its most moving sequence — Wade commits suicide by walking at night into the raging Malibu surf, followed helplessly by Marlowe and Wade’s wife Eileen (Nina van Pallandt), who are unable to save him.

Some other differences: in the screenplay, Marlowe has two scantily clad female neighbors who practice yoga all the time; in the movie, there are five or six of them. In the movie, the favorite food of Marlowe’s cat is “Coury Brand Cat Food”; in the screenplay, it is “Pussy Delight”. Another sequence invented during shooting was the scene where gangster Marty Augustine and his thugs (including future governor Arnold Schwarzenegger) strip down to their underwear in a bizarre attempt to intimidate Marlowe. Omitted from the film is a screenplay sequence taking place in Marlowe’s office. In the movie, he gets his telephone messages from a neighborhood bar.

Marlowe was conceived by Brackett and Altman as a character from another era (“Rip Van Marlowe”), his 1940s ethics contrasting sharply with the peculiar New Age culture of Los Angeles in the early 1970s.

The film is constantly referencing Hollywood, Hollywood movies, and the film industry, even though none of its characters are actual film people. Rarely has a screenplay or movie so deftly balanced tongue-in-cheek sequences with scenes of deadly seriousness.

Together, Brackett, Altman, his cinematographer, and his remarkable cast created a neo-noir masterpiece. By itself, Leigh Bracket’s screenplay adaptation of The Long Goodbye is an outstanding piece of work and remains a compelling read.

Collation: NOTE: blue revision pages undated, pink pages dated 6/21/72. [title] (5/22/72, notation), A-D (blue), 1-5 (blue), SA (blue), 6-7, 8 (blue), 8A (blue), 9-13, 14-15 (blue), 16-17, 18 (blue), 18A (blue), 19, 20-24 (blue), 24A-248 (blue), 25, 26-27 (blue), 27A (blue), 28, 29-30 (blue), 30A (blue), 31-34 (blue), 34A (blue), 35-38, 39 (blue), 39A (blue), 398 (pink), 39C (blue), 40-43 (pink), 43A-43C (pink), 44-46 (blue), 46A-46C (blue), 47 (blue), 47A (blue), 48-52, 53 (blue), 54-55, 56 -57 (blue), 58-59, 60 (blue), 61-62, 63-64 (blue), 65-70, 71-72 (blue), 73-75, 76-77 (blue), 77A (blue), 78-79 (blue), 79A (blue), 80-87 (blue), 88-89 (blue, 6/1/72), 90-91 (blue, combined, 6/1/72), [printer imprint].

Out of stock

Related products

-

SLEEP ON THE ROOF (1967) Unproduced script based on the life of Margaret Sanger

$500.00 Add to cart -

LOOT (ca. Sep 1969) Final Draft screenplay

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

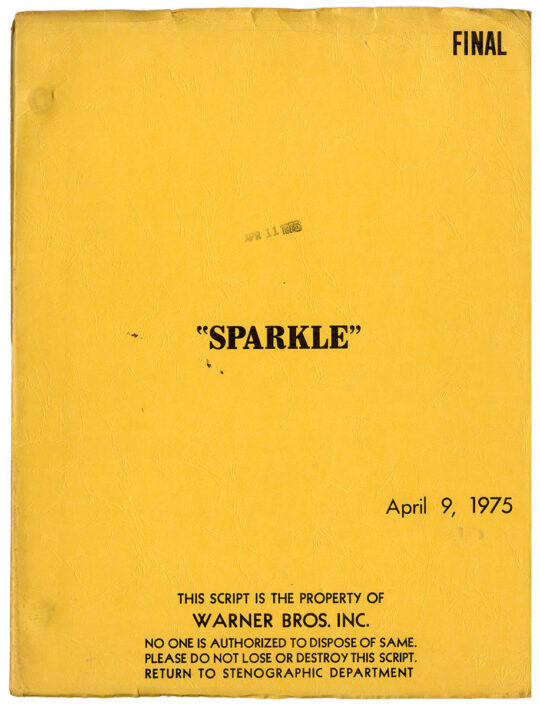

(Blaxploitation film) SPARKLE (Apr 9, 1975) Final Draft film script by Joel Schumacher

$750.00 Add to cart -

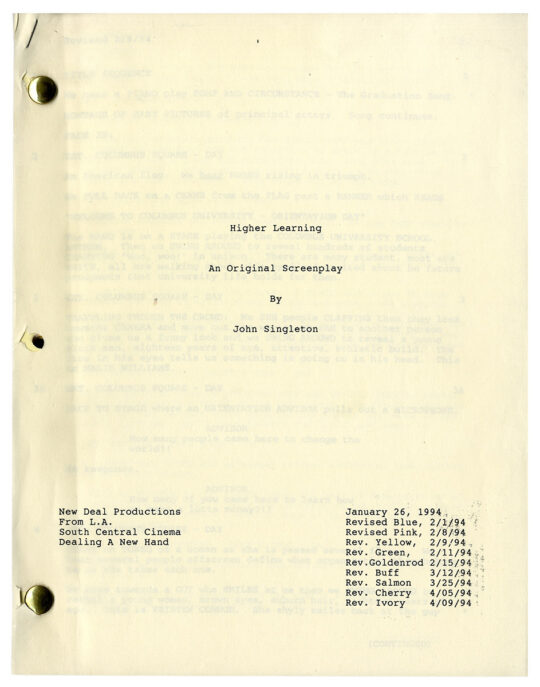

John Singleton (writer, director) HIGHER LEARNING (Jan 26, 1994) Rainbow film script

$500.00 Add to cart