RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT, A (1987) Larry Cohen-signed archive

Stephen King (source) New York: Fifi Oscard Associates, [1987]:

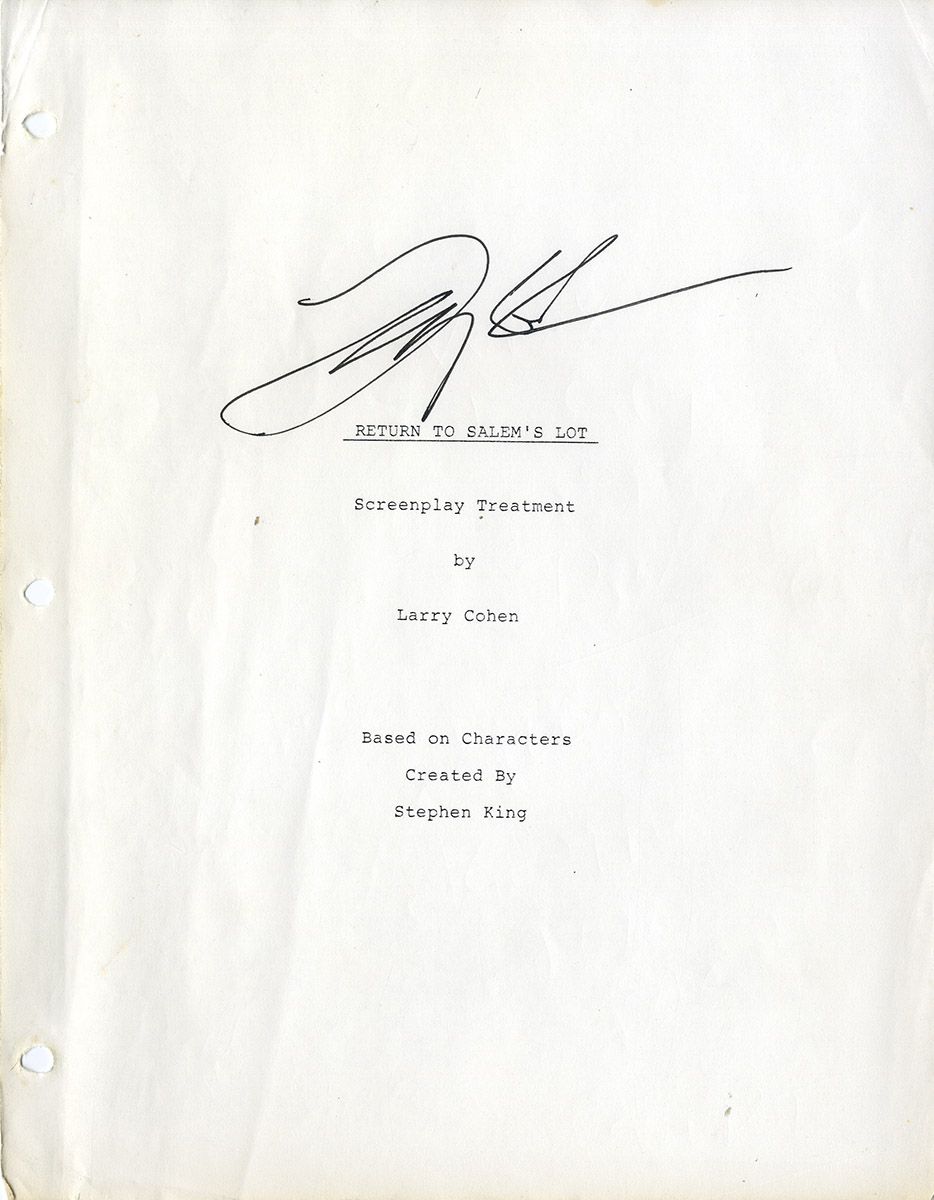

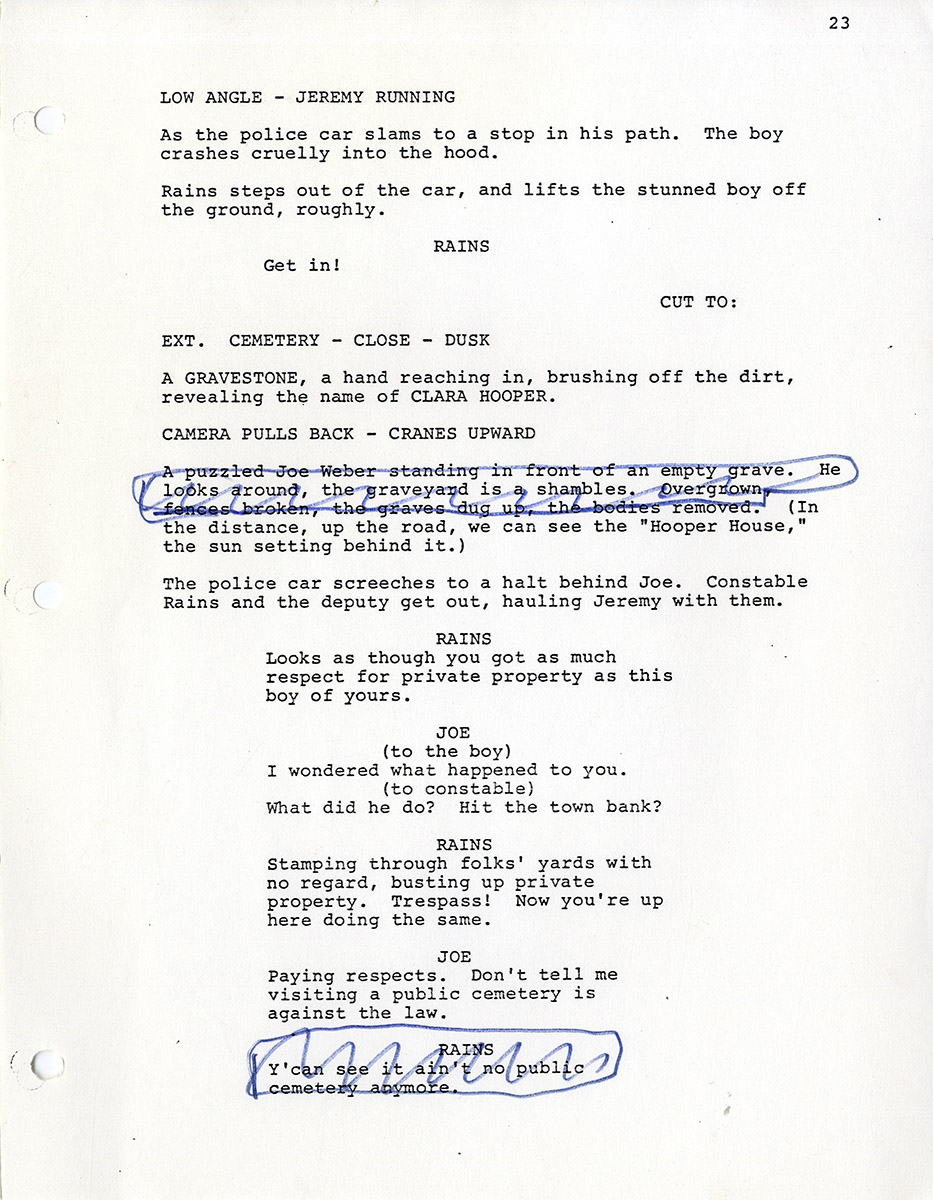

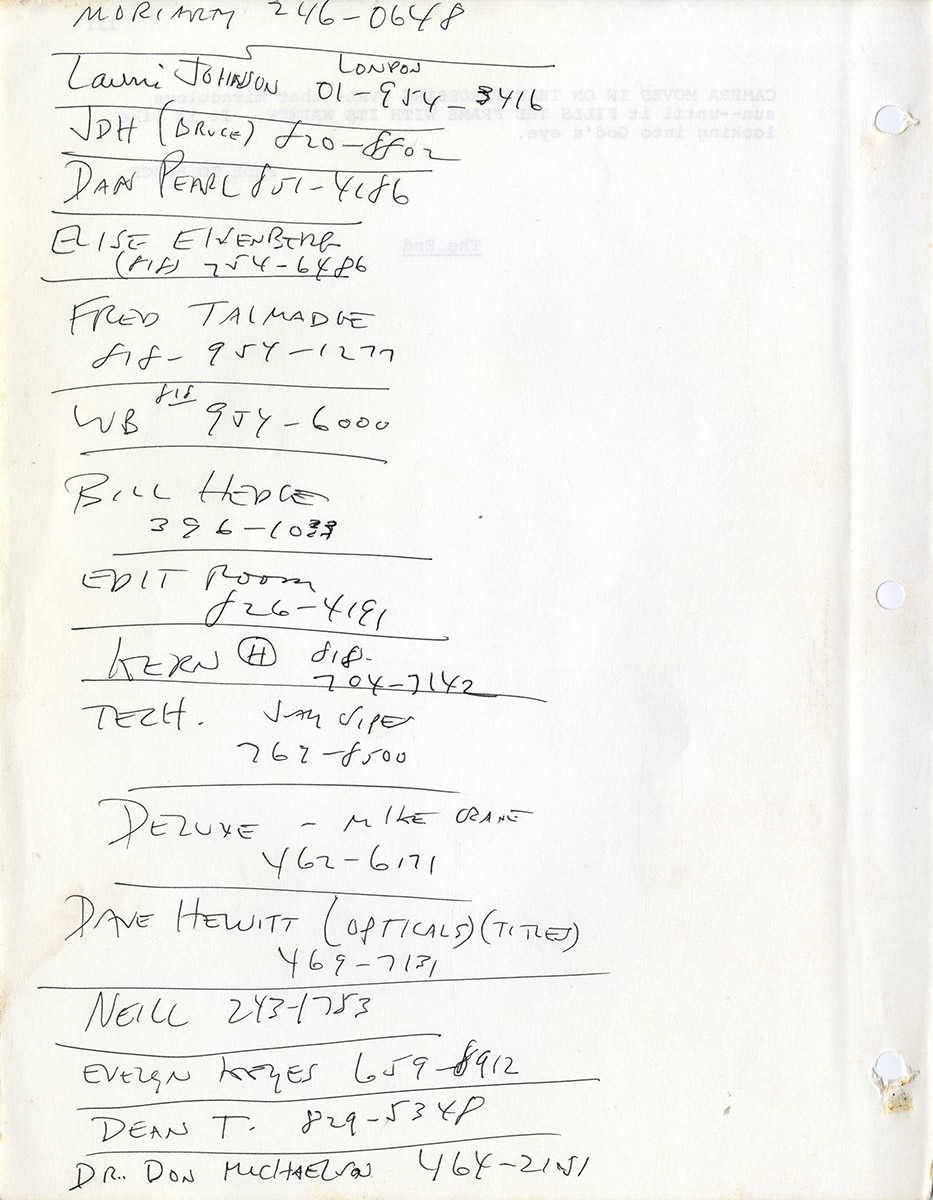

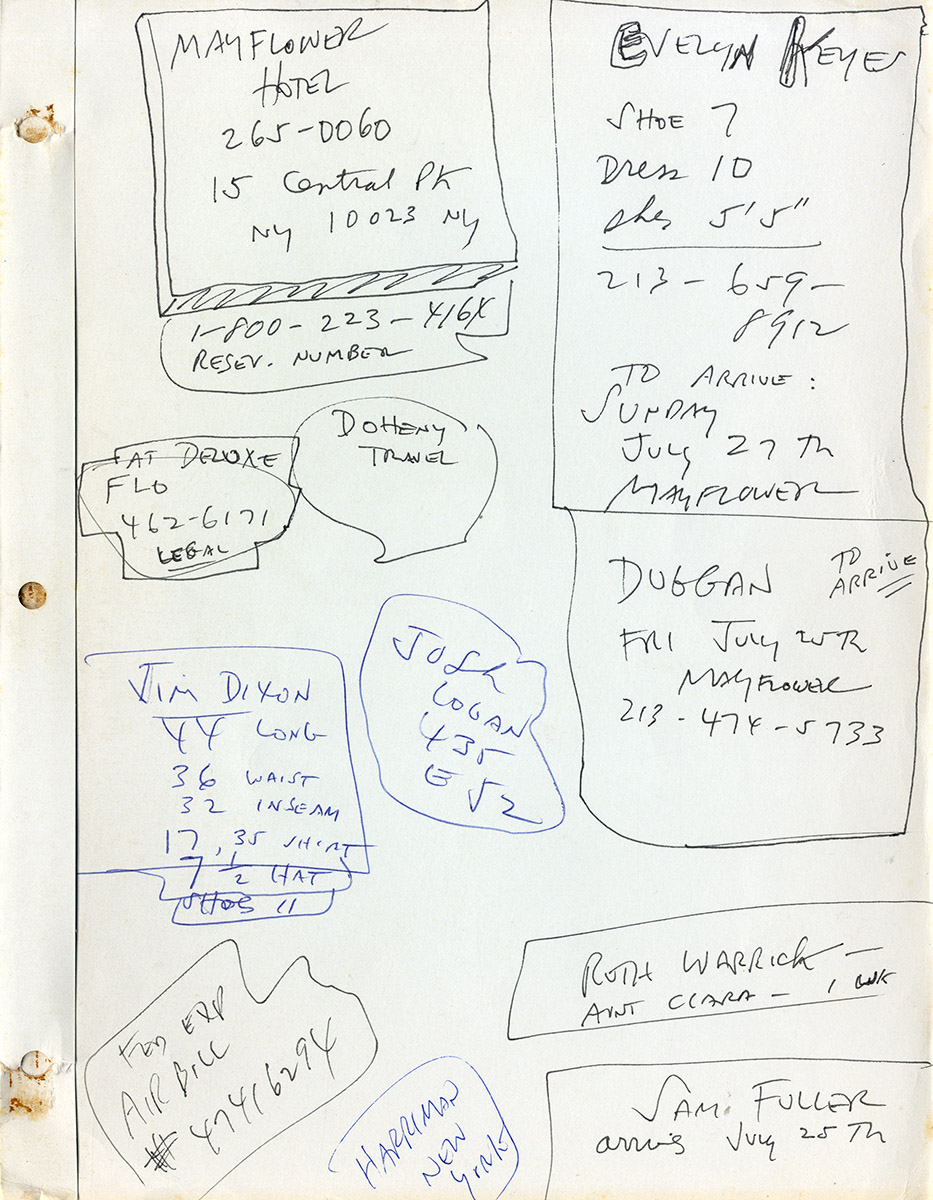

– Screenplay treatment by Larry Cohen, undated (ca. 1986) Self-wrappers, brad bound, 38 pp., with various MS annotations in Cohen’s hand throughout and on the back blank wrapper, 11 x 8 ½” (28 x 22 cm.) Signed by Cohen on title page. Near fine.

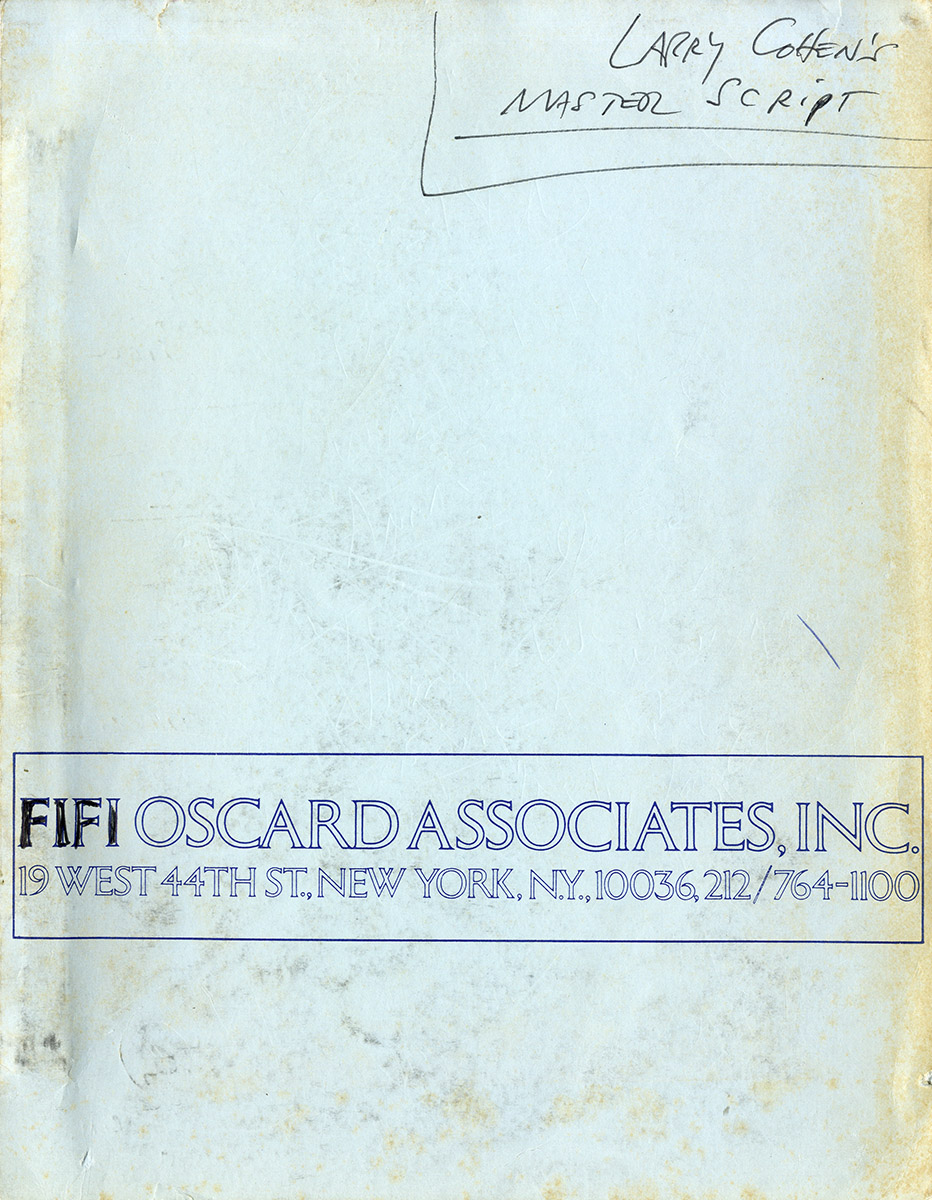

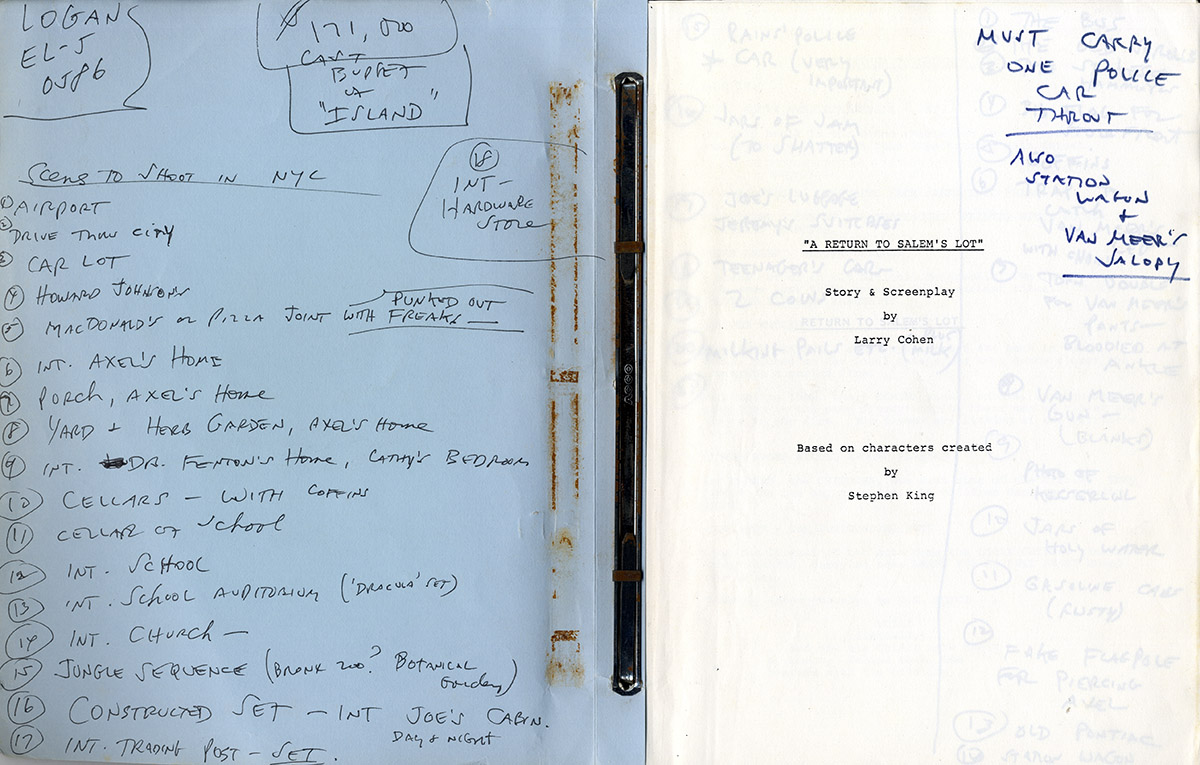

– Revised screenplay by Larry Cohen, [1987] Printed agency wrappers,121 pp. brad bound, 11 x 8 ½” (28 x 22 cm.) With scattered MS notes throughout and heavy annotation on inner wrapper and back of final page, all in Cohen’s hand. Bound with a metal clasp, with corresponding rust stains on the two inner wrappers, light staining to front wrapper, overall very good+ or better.

An archive representing one of Larry Cohen’s most notable horror films, from his estate and with handwritten notes in his hand.

Larry Cohen’s two greatest assets as a writer/filmmaker are his conceptual brilliance and the way he works with actors. In A RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT, he took the original ideas of Stephen King’s 1975 best-selling novel SALEM’S LOT (filmed as a 1979 TV miniseries by Tobe Hooper) and added his own distinctively Cohenian twists.

A RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT was part of a two-picture deal Cohen made with Warner Brothers that began when Cohen went to the studio with Andre De Toth and pitched them the idea of remaking HOUSE OF WAX (1953). Uninterested in the HOUSE OF WAX remake, the studio suggested as an alternative that Cohen should make something for their direct-to-video division, a sequel to his 1974 hit, IT’S ALIVE. Cohen said okay on the condition that Warner would finance two films to be shot back-to-back, the idea being that shooting two films in this way using the same crew and some of the same actors, could provide greater production value for both projects. The two films that resulted were ISLAND OF THE ALIVE, the third film in the IT’S ALIVE franchise, shot mostly in Hawaii, and A RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT, another project with name-brand recognition, shot mostly in New England.

In the first paragraph of a treatment accompanying the screenplay, Cohen described the basic premise of his ‘SALEM’S LOT sequel as follows:

Imagine a small village nestled in the New England countryside populated by vampires. A vampire community that lives only at night, a village that has survived this way for centuries. Here in this place where the pilgrims came seeking asylum from persecution in Europe, came the world’s most persecuted sect—the vampires themselves. Seeking in the New World a place to hide and to multiply.

Cohen’s sequel departs from King’s original in several significant respects. In the King novel and miniseries, a vampire, Mr. Barlow, and his familiar, arrive in the town of Jerusalem’s Lot and proceed to vampirise the entire community. In Cohen’s version, the vampires have dominated the town since the early 1600s. In the King version, the vampires are fought by a trio of males: a young man, an old man and a boy. In Cohen’s sequel, the vampires are also fought by a trio of young man, old man and boy, but they are not the same three as in the King version. In fact, none of the characters from King’s version reappear in the Cohen sequel.

Like most of Cohen’s best films, A RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT has a political subtext. His genteel vampires are “old money”, a metaphor for America’s white, propertied ruling class, and the screenplay’s dialogue emphasizes their wealth:

ELDER

We’re all wealthy people. Can you imagine how rich

you’d be if you got to live three hundred years?

ANOTHER ELDER

What with just real estate alone. And we own land

on Boston Common and property all up and through

Maine and New Hampshire–why, vampire life and

financial security go together.

Which is why some commentators have referred to the bloodsuckers in this Reagan-era film as “Republican vampires”.

During the daytime while the vampires are asleep, the town is managed by working class “drones”, a race of human-vampire hybrids, raised by the vampires to take care of all the menial tasks that need doing and to protect their vampire overlords. In short, the vampires are a metaphor for the one-percent, while the exploited drones represent everyone else. The drones, in turn, raise cattle which are the primary source for the blood the vampires need to survive when they are not feeding on the occasional human.

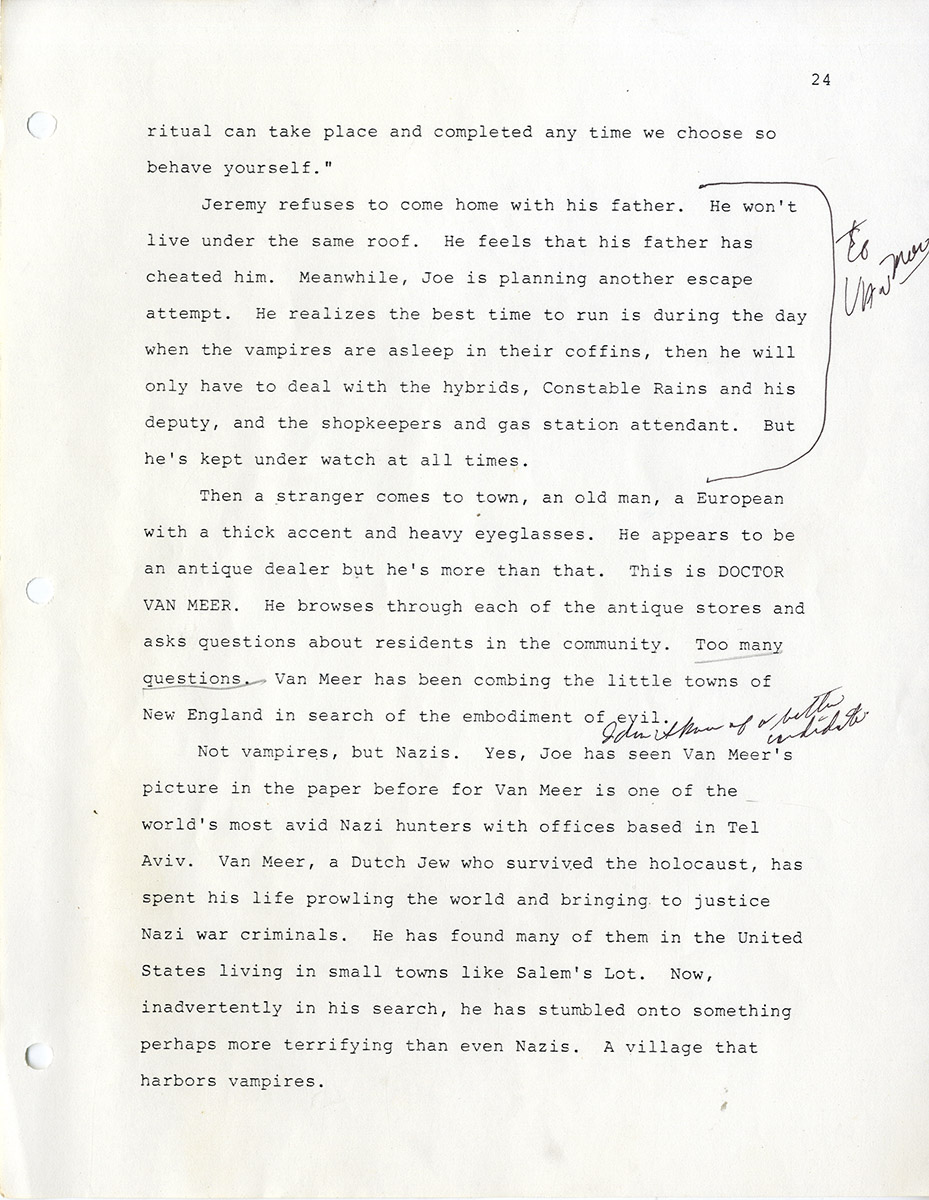

The screenplay’s first act introduces us to Joe (Michael Moriarty) , a renowned anthropologist who returns to the States from filming tribes in South America in order to take care of Jeremy, his troubled 11-year-old son. In the second act, Joe and Jeremy travel to Salem’s Lot where a relative has left Joe some property, and they meet the community of vampires, led by the distinguished Judge Axel (Andrew Duggan). As it turns out, Judge Axel has brought Joe to Salem’s Lot for the specific purpose of employing Joe’s skills as an anthropologist to write a chronicle of the vampire settlement. Joe and Jeremy are gradually seduced into the vampire community, Joe by a childhood sweetheart, a vampire, still looking like the beautiful 17-year-old he remembers from so many years ago, and Jeremy by a vampire girl-child who appears to be the same age he is. In the third act, an elderly stranger named Van Meers arrives (a part written for and played by director Samuel Fuller), a Nazi hunter like the real-life Simon Wiesenthal who will soon turn into a vampire hunter when he realizes the Nazi-like nature of the community he has stumbled upon. He, in turn, will free Joe and Jeremy from the influence of the vampires (“Disenchantment has set in“), and the three of them will band together to destroy the community of monsters.

There are no major differences, apart from some tweaking of the dialogue, between the screenplay’s first act as written by Cohen and the way he films it. The second act, on the other hand, in which Joe and Jeremy arrive in Salem’s Lot, has been considerably revised and reordered, mainly to introduce the vampire horror threat much sooner. The movie includes a brief montage of the town’s New England homes, not in the screenplay, with whispered voiceover by the vampire characters. We also see a scene not in the screenplay of some of the vampires waking up, reminiscent of a similar scene in Tod Browning’s 1931 DRACULA. The order of the first two vampire attacks — one by the child vampires on a pair of hoboes, the second by adult vampires on a group of teenagers — has been reversed, and in the latter scene the movie introduces a hideous Nosferatu-like monster, amping up the scare factor, who turns out to be “other face” of the kindly-appearing Judge Axel. The film’s third act, dominated by the Fuller character, has been somewhat revised so that the boy Jeremy, actively involved in the screenplay’s vampire killing, is left behind in a church in the movie, all the better to be captured by the vampires and used as a hostage.

Throughout the screenplay and film, there is imagery that links the vampires with America and its Founding Fathers. A classroom scene begins with the vampire children reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. Judge Axel is ultimately killed by the pole of an American flag used as a wooden stake.

The screenplay ends with a shot of our three heroes driving off into the morning sun. The movie, on the other hand, ends with shots of the vampires’ cattle who, of course, represent how humans are perceived by the story’s elitist master race.

Out of stock

Related products

-

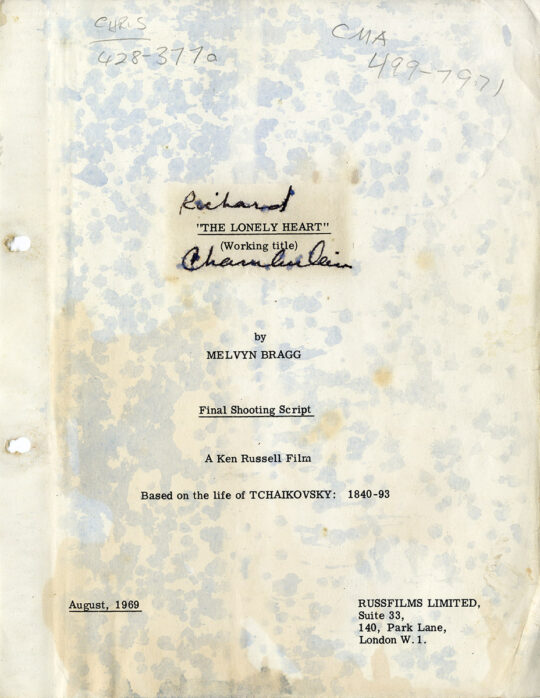

Ken Russell (director) THE MUSIC LOVERS [working title: THE LONELY HEART] (1969) Final shooting script

$3,000.00 Add to cart -

(African American film) A PIECE OF THE ACTION [working title: SOMETHING BIG COMING UP] (Nov 1, 1976) Film script

$750.00 Add to cart -

CROSS CREEK (Feb 9, 1982) Rev Final Shooting script by Dalene Young

$750.00 Add to cart -

DRESS GRAY (Mar 6, 1981) Second revision script by Gore Vidal

$500.00 Add to cart