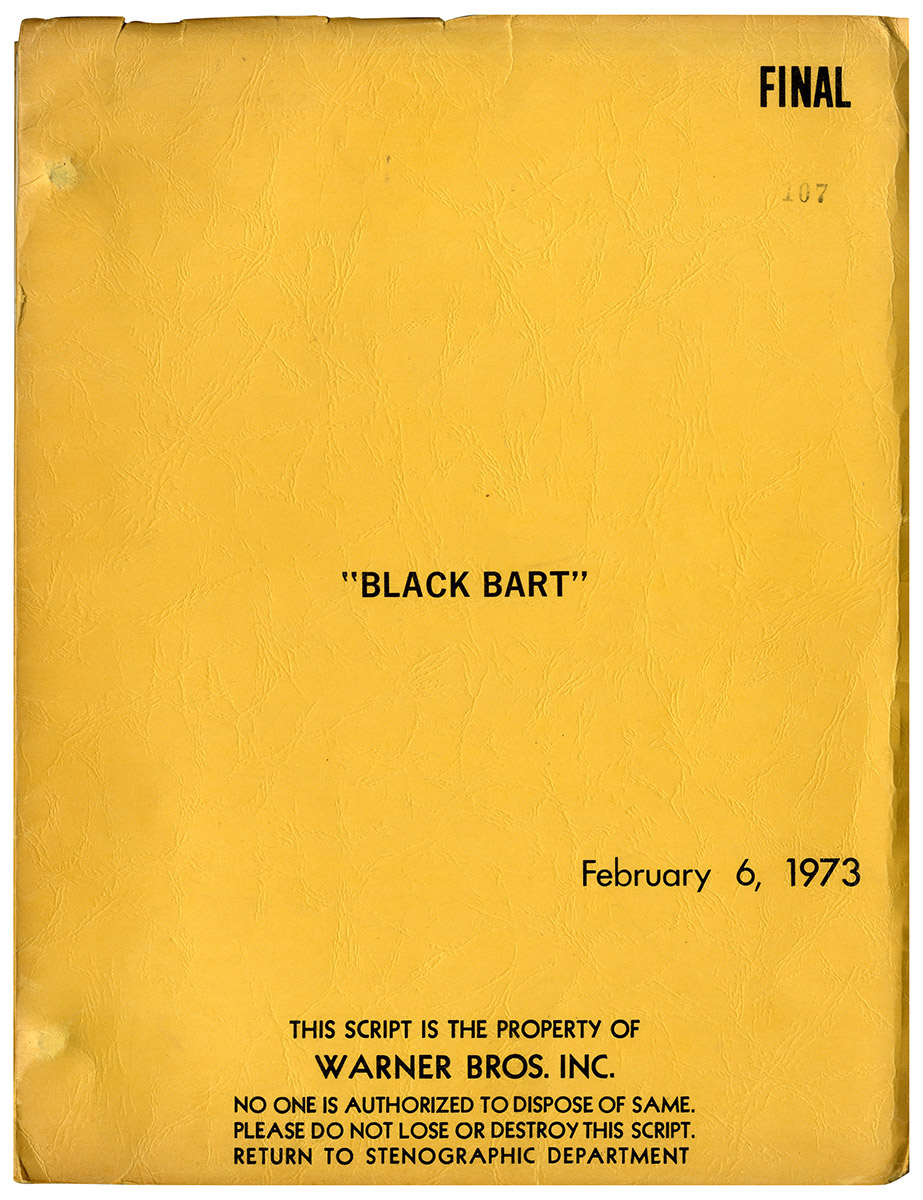

Richard Pryor (co-screenwriter), Mel Brooks (director) BLAZING SADDLES [working title: BLACK BART] (Feb 6, 1973) Final film script

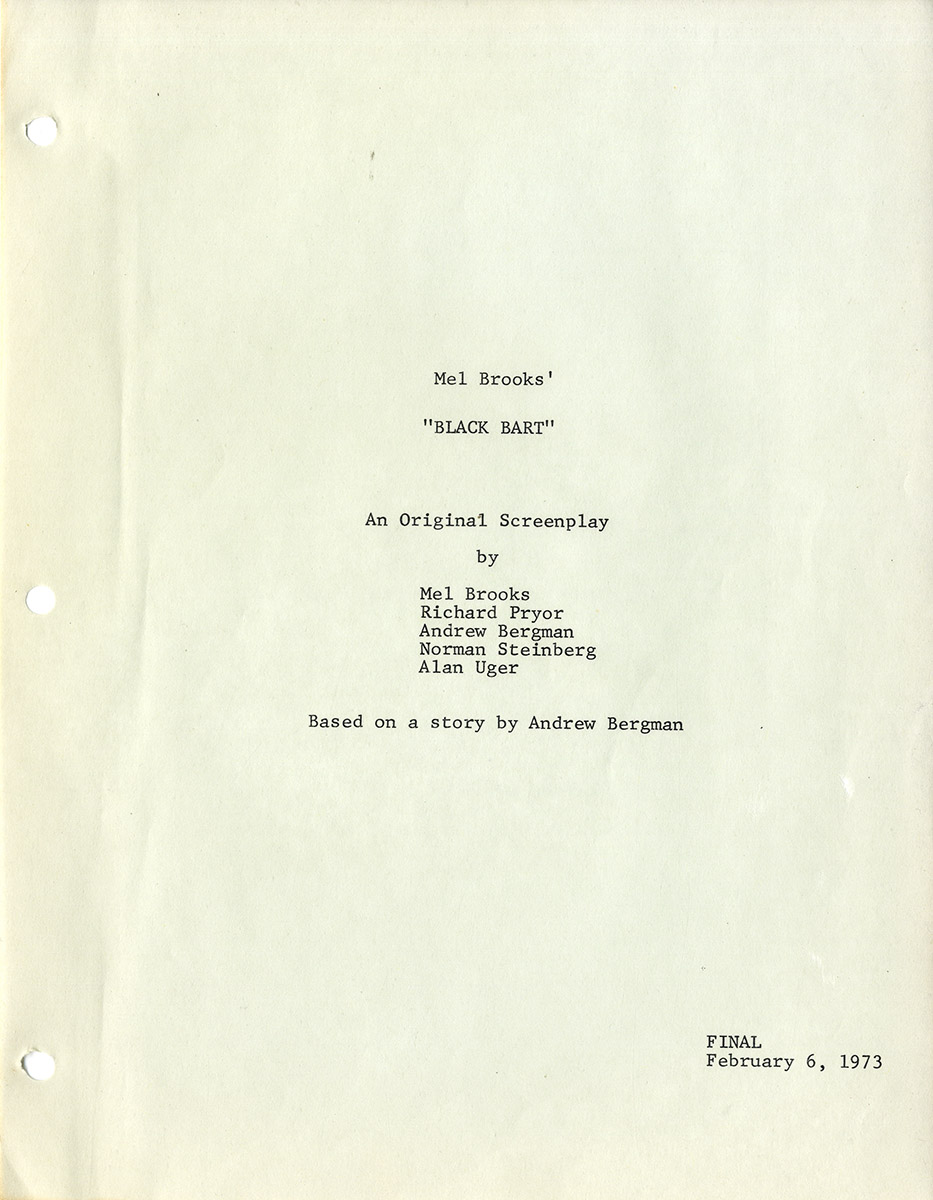

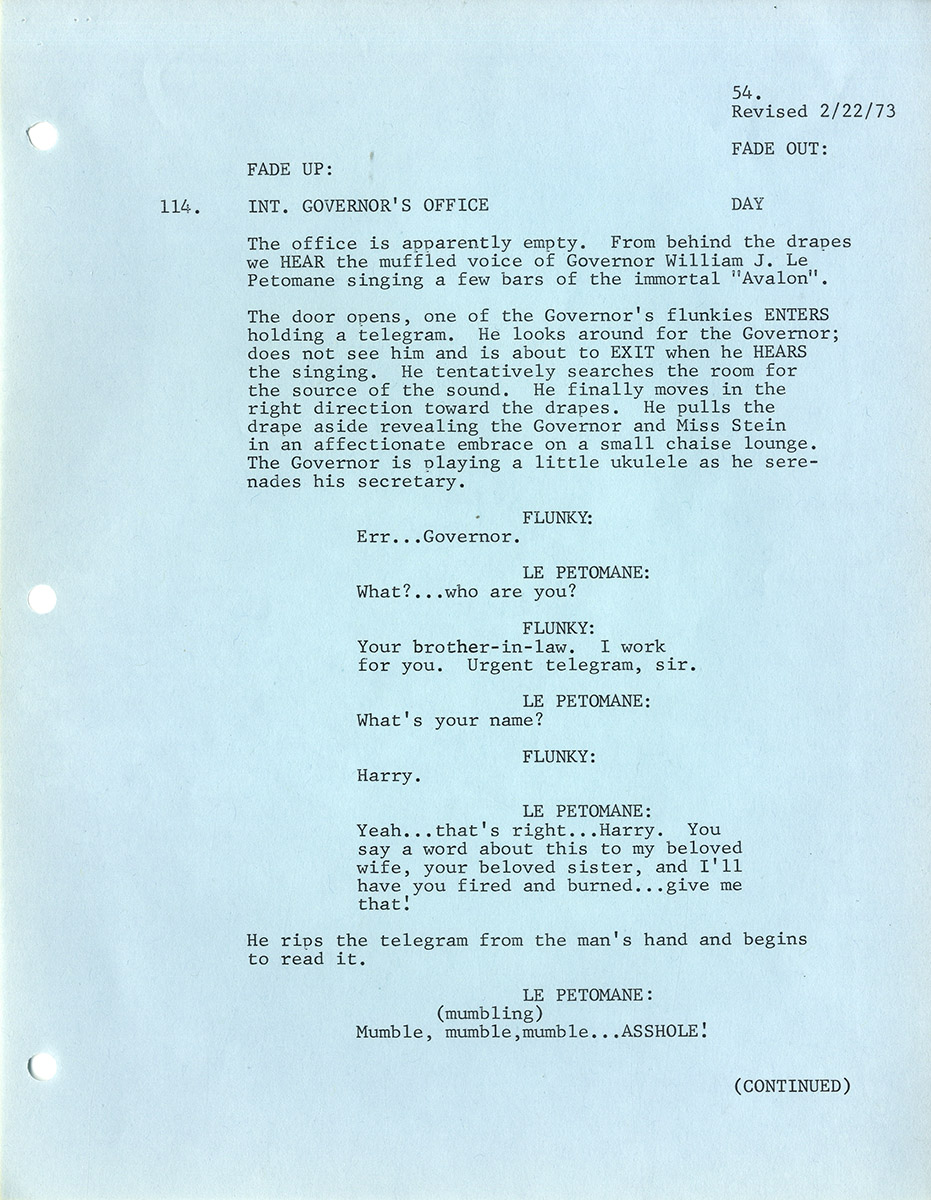

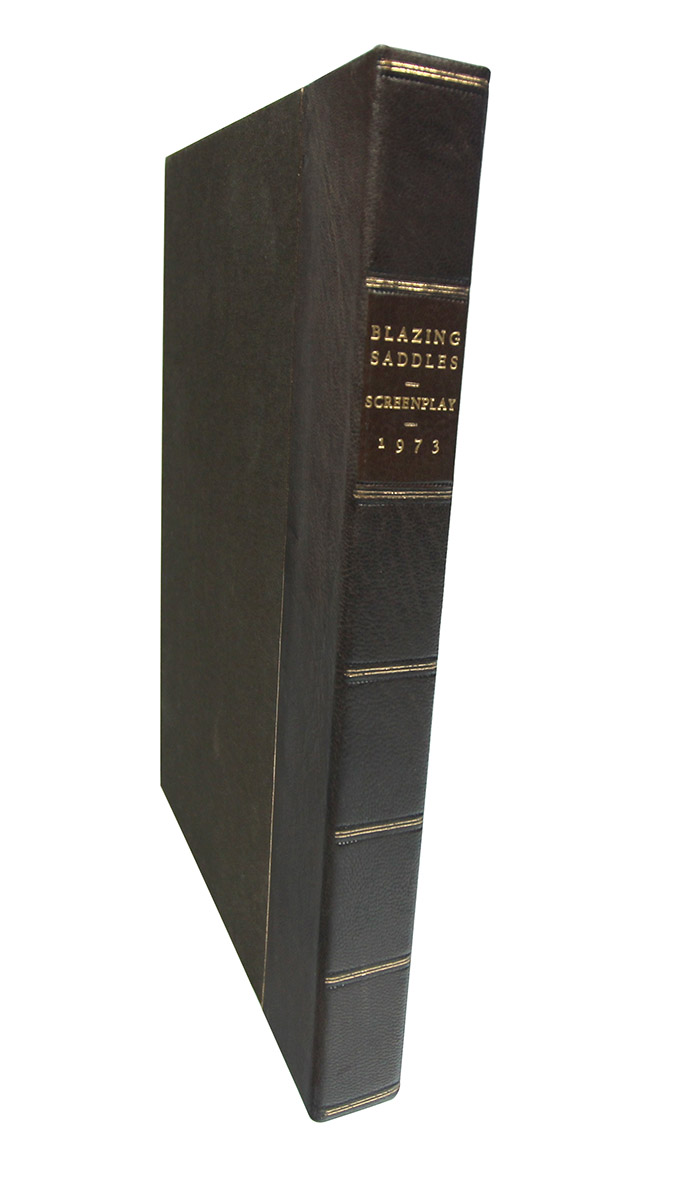

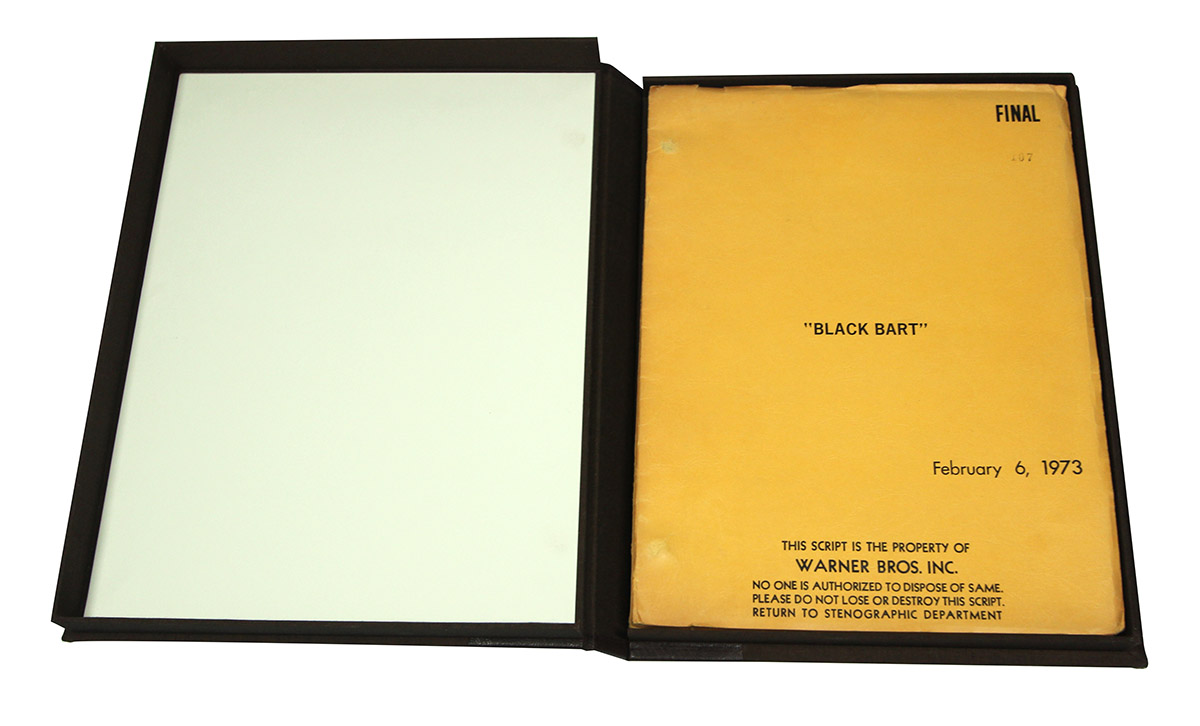

Burbank, CA: Warner Brothers, 1973. Vintage original film screenplay, 11 x 8 1/2″ (28 x 22 cm.) Printed titled studio wrappers, noted as FINAL, dated February 6, 1973. Title page present, with credits for Brooks, Pryor, Andrew Bergman, Norman Steinberg, and Alan Unger. 132 leaves, with last page of text numbered 124. Brad bound, mimeograph, with blue revision pages throughout, dated 2/9/73 through 2/27/73. Near fine, in a custom brown quarter-leather clamshell box.

Final script for the 1974 film, seen here under the working title Black Bart.

Consistently cited as one of the greatest and/or funniest film comedies of all time, Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles came about through a series of happy accidents. It began as a screen treatment by Andrew Bergman about a Black sheriff called Tex X (as in Malcolm X). It was originally supposed to be directed by Alan Arkin with James Earl Jones in the lead. After the Arkin/Jones version fell apart, the project was offered to Mel Brooks who was immediately taken with it and assembled a team of writers including himself, Andrew Bergman, Richard Pryor (known then mainly as a Black stand-up comedian), Norman Steinberg and Alan Uger. The five of them worked together in a room shouting ideas back and forth, a process that Brooks later compared to the way he had worked with other writers on Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows.

The February 3, 1973 final screenplay draft was entitled Black Bart, and Brooks originally wanted to cast the comparatively unknown Pryor in the title role, but the studio did not approve, so Tony-winning stage star Cleavon Little was cast instead. Likewise, the part of Bart’s sidekick the Waco Kid was originally conceived for a much older actor. Dan Dailey and Gig Young were successively cast in the part, but had to drop out for health reasons. Gene Wilder, with whom Brooks had been collaborating on the Young Frankenstein screenplay, was literally an overnight replacement. The warm relationship between Cleavon Little’s Black Bart, a character co-written by Richard Pryor, and Gene Wilder’s Waco Kid foreshadows the on-screen relationship between Pryor and Wilder in a series of four comedies, starting with Silver Streak (1976), that the duo would make together during the next decade and a half.

Blazing Saddles is remembered today for its groundbreaking vulgarity — its inspired use of comic profanity (even the dreaded N-word) and, especially, its scene of bean-eating cowboys farting around a campfire. It was the intention of Brooks and company to satirize every movie Western ever made. However, Blazing Saddles is more than a genre parody. The most prominent target of its satire is white racism. Irrational prejudice against Black people, as Brooks observed, is the engine that drives the film’s comic narrative.

Almost every gag, verbal or visual, that appears in the movie can be found in the screenplay which, in fact, has many more gags and jokes than were actually used. One typical visual gag that was cut from the film has Bart repainting the black face of a lawn jockey white. Other gags were improved in the transition from script to screen, for example, in the script when villain Hedley Lamarr (Harvey Korman) asks his henchman Taggart (Slim Pickens) how they might terrorize the town, Taggart suggests, “What about killing the first born male child in each household?” and Lamarr responds, “No, that’s been done to death.” In the movie Lamarr’s response is, “No, too Jewish.”

Much of the screenplay’s humor is based on anachronism and pop culture references, as when Taggart says to Lamarr (in a line omitted from the film), “Gol durnit, Mr. Lamarr, I ain’t heard such pretty talk since I seen Charles Boyer as Pepe Le Moko!” One of the movie’s most fondly remembered characters is the vamp, Lili Von Shtupp (Lily Von Dyke in earlier drafts), a parody of Marlene Dietrich’s singing saloon girl in Destry Rides Again, a caricature so brilliantly executed by performer Madeline Kahn that it earned her an Academy Award nomination as Best Supporting Actress.

Blazing Saddles is all about the breaking of boundaries, not just the boundaries of racism that divide Black people and Native Americans from whites, but boundaries of every kind. The movie gleefully attacks the boundaries of good taste. Eventually the fourth wall — the boundary that separates a movie from its audience — is broken down entirely as the characters from Blazing Saddles break out of their 19th century Western set and invade the studio’s other sets, notably a soundstage where a musical is being rehearsed, and finally pour out into the streets and into a contemporary movie theater (Grauman’s Chinese) that is screening — what else? — Blazing Saddles.

Often imitated, never surpassed, Blazing Saddles retains its status as a classic of American comedy.

Out of stock

Related products

-

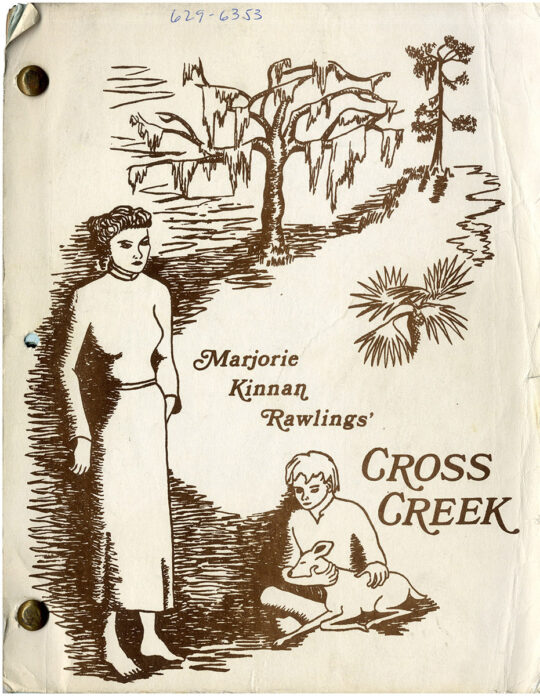

CROSS CREEK (Feb 9, 1982) Rev Final Shooting script by Dalene Young

$750.00 Add to cart -

![MON ONCLE D'AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French screenplay](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/MonOncleDAmeriqueFR-SCR_a-540x745.jpg)

Alain Resnais (director) MON ONCLE D’AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French film script

$2,500.00 Add to cart -

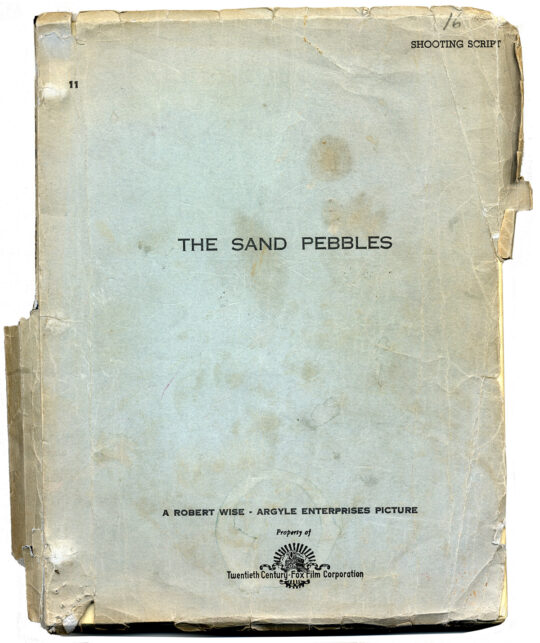

SAND PEBBLES, THE (Nov 1, 1965) Shooting script by Robert Anderson

$1,150.00 Add to cart -

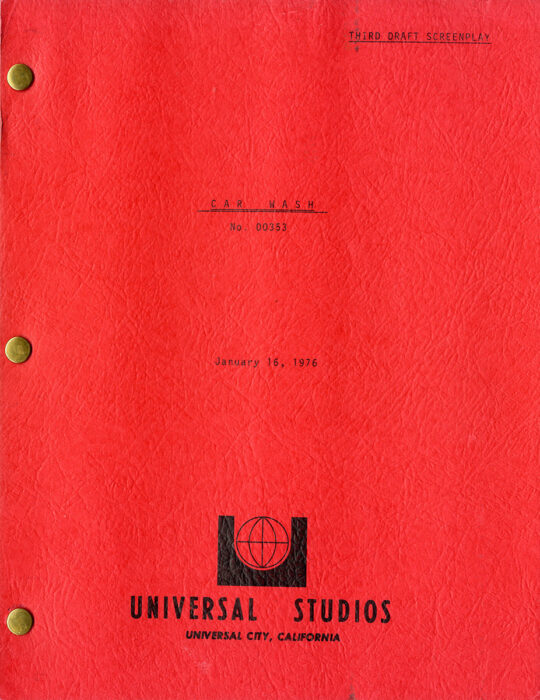

(African American film) CAR WASH (1976) Third draft film script by Joel Schumacher

$850.00 Add to cart