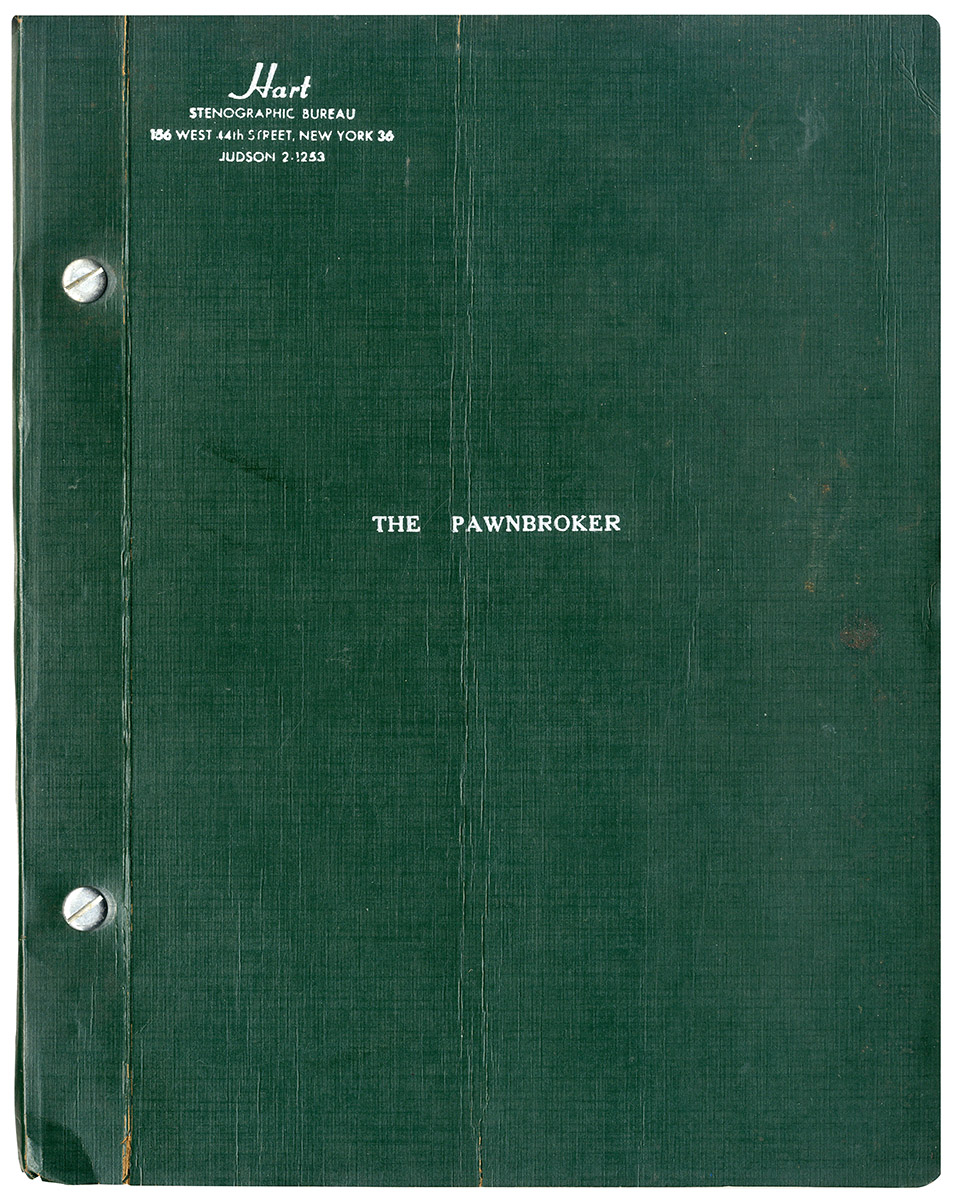

Sidney Lumet (director) (Holocaust film) THE PAWNBROKER (ca. 1963) Film script

[New York]: The Landau Company, [ca. 1963]. Vintage original film screenplay, 11 x 8 1/2″ (28 x 22 cm.), printed leatherette covers, brad bound, mimeograph, 121 pp., light vertical creasing to front wrapper, near fine.

Historians have called The Pawnbroker the first feature produced entirely in the United States to deal with the Holocaust from the point of view of a survivor. Years before the term “survivor guilt” became part of the common vocabulary, The Pawnbroker took a look at that phenomenon.

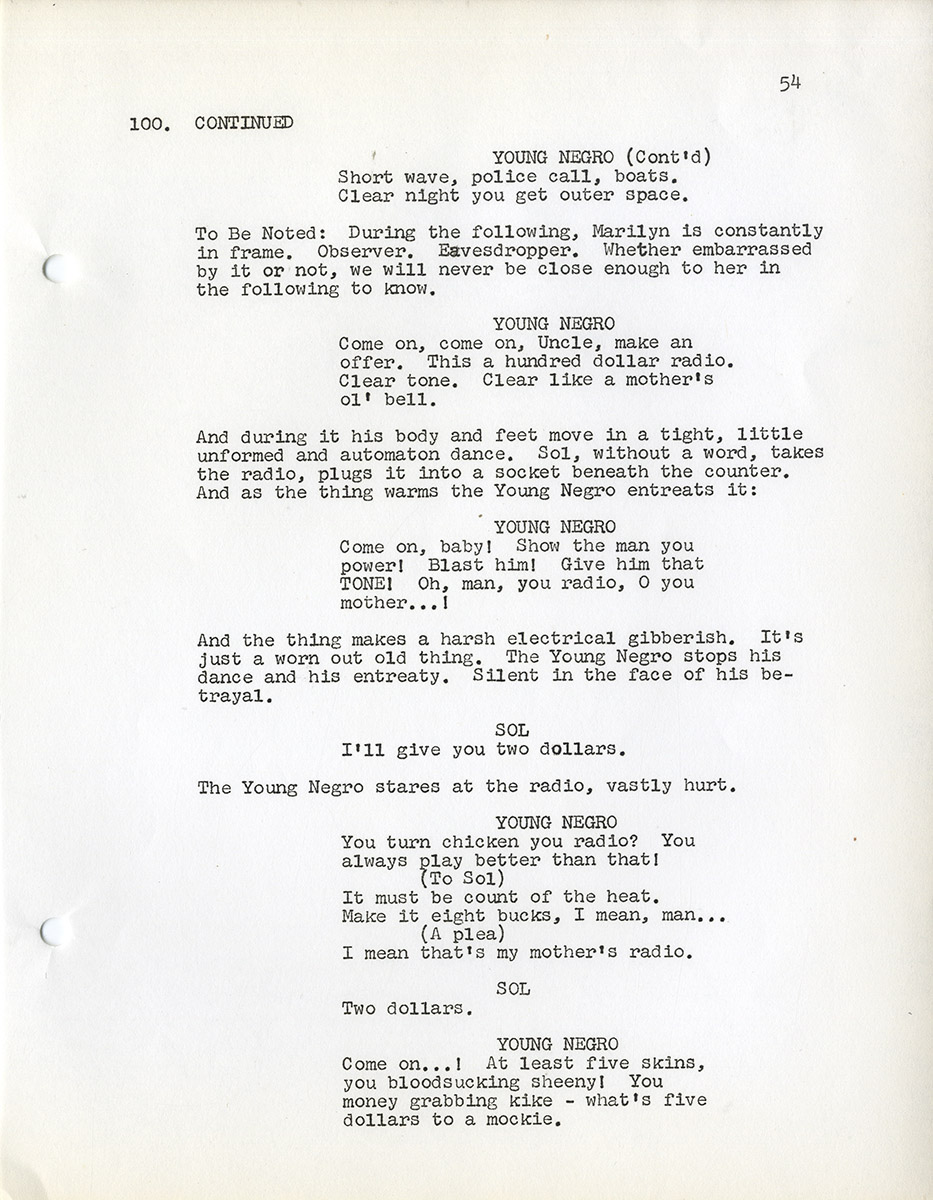

The Pawnbroker is not just a classic Jewish film. Shot on location in New York’s Harlem district, it is a movie of extraordinary groundbreaking diversity that includes Jewish characters, Black characters, Hispanic characters, and gay characters. There are memorable performances by Black actors Juano Hernandez, Brock Peters and Raymond St. Jacques. It introduced the first of forty film scores by legendary Black jazz composer and music producer Quincy Jones. The second lead is played by Jaime Sánchez, an actor of Puerto Rican descent. Rod Steiger, who plays the title role, considered it the finest performance of his career.

Sol Nazerman, the pawnbroker, is a man who lost everything in a concentration camp – his wife, his parents, his daughter and his little son. At present, he lives in the suburbs of Long Island with his sister-in-law and her family. Everyday he commutes from Long Island to his pawnshop in Harlem. He has an assistant, an ambitious young Puerto Rican named Jesus Ortiz, whose energy and cheerfulness contrasts sharply with Sol’s dour demeanor. The pawn shop’s clients whom Sol deals with on a daily basis are a wretched lot, desperately in need of money, or in one case, just someone to talk to. Sol has a mistress, the wife of Sol’s best friend who died in the camp. She lives in a New York apartment with her elderly father who asks Sol, “Does blood flow through you, Nazerman? Do you feel pain?” To which Sol replies, (Very quiet) “No.”

The screenplay by Morton S. Fine and David Friedkin periodically flashes back from the Harlem present to Sol’s concentration camp past. The story’s narrative arc is a series of disturbing events, culminating in the death of Sol’s assistant during an attempted robbery, that force Sol to feel again — even if what he ends up feeling is his own extreme grief.

The film, directed by Sidney Lumet, follows the screenplay quite closely, at least as far as its dialogue is concerned. When it comes to the screenwriters’ description of action and how a scene should be shot, Lumet tends to disregard the screenwriters’ detailed instructions and shoot things his own way. The film’s extraordinary visuals are due in large part to its great cinematographer, Russian-born Boris Kaufman, a frequent Lumet collaborator and a master of his craft who worked on films as classic and diverse as Jean Vigo’s L’Atalante and Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront.

The film differs from the script structurally. A scene showing Sol at home with his Long Island family is moved from the middle of the screenplay to the film’s beginning. A scene involving a corrupt cop who enters Sol’s pawnshop is omitted altogether. One of the most striking and memorable aspects of the film — not in the screenplay — are the frequent flash cuts, sometimes as brief as two frames, from the present to the past, a device which the film’s editor Ralph Rosenblum claims to have contributed. Other instances of cross-cutting, such as between the enthusiastic lovemaking of Jesus and his girlfriend, and the tired near-lifeless lovemaking of Sol and his mistress, derive from the screenplay. In the scenes at the richly furnished apartment of the Harlem crime boss Rodriguez, played by Brock Peters, director Lumet makes another significant (non-verbal) addition: the presence of a beautiful young man attending to Rodriguez, indicating that the crime boss is gay. Flash cuts to the bare breasts of Jesus’s girlfriend, seen from Nazerman’s point of view, were made in defiance of the 1964 Production Code and signaled the eventual end of that Code.

The Pawnbroker is an unabashed art film, a foundational independent movie that helped to jump-start America’s New Wave. Its remarkable New York location shooting, combining neo-realism with cinematographer Boris Kaufman’s extraordinary use of light and shadow, makes this one of the definitive New York movies, and one of the movies that established Sidney Lumet as the definitive New York film director.

Out of stock

Related products

-

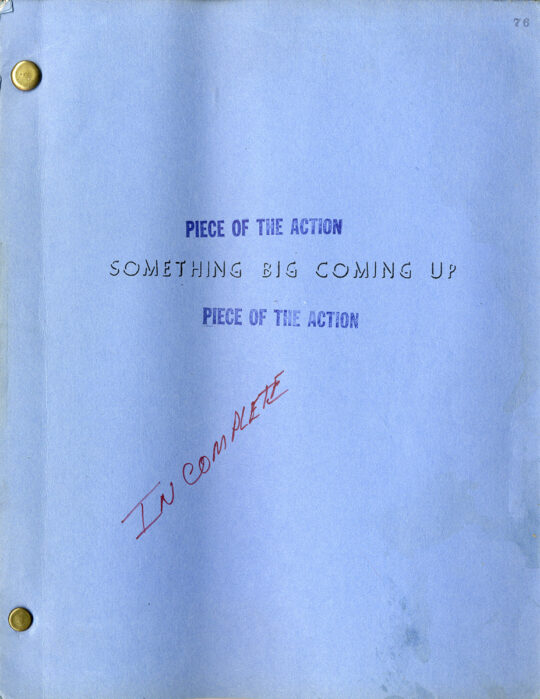

(African American film) A PIECE OF THE ACTION [working title: SOMETHING BIG COMING UP] (Nov 1, 1976) Film script

$750.00 Add to cart -

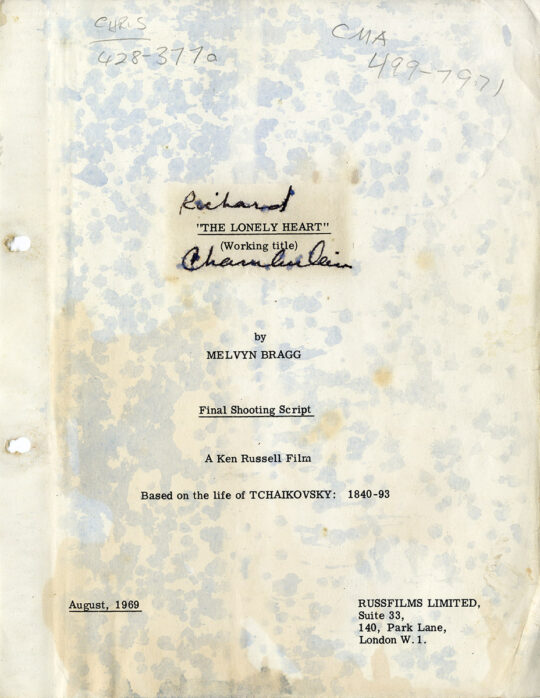

Ken Russell (director) THE MUSIC LOVERS [working title: THE LONELY HEART] (1969) Final shooting script

$3,000.00 Add to cart -

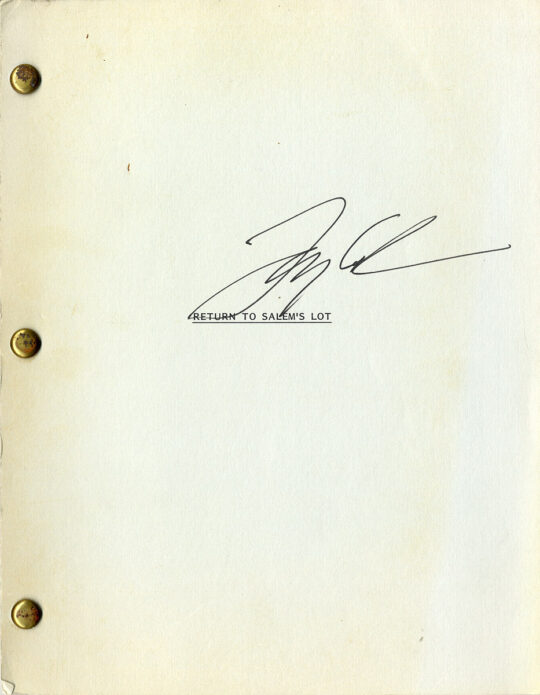

RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT, A (1987) Larry Cohen-signed script

$625.00 Add to cart -

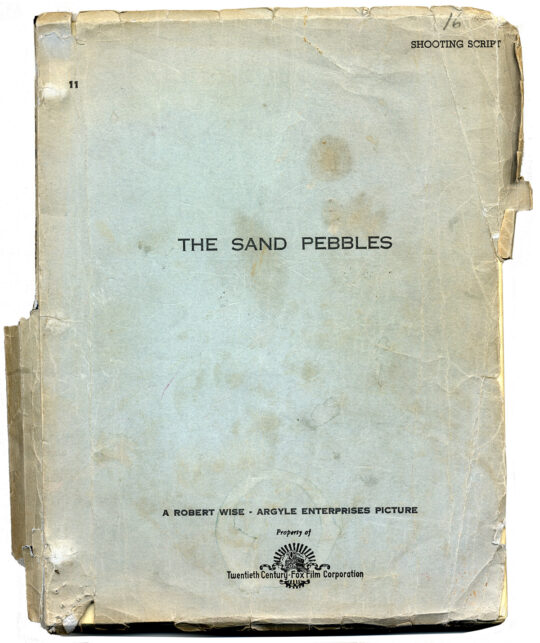

SAND PEBBLES, THE (Nov 1, 1965) Shooting script by Robert Anderson

$1,150.00 Add to cart