Stanley Kramer (director), Scopes Trial (subject) INHERIT THE WIND (Aug 13, 1959) Revised draft film script by [Nedrick Young] and Harold Jacob Smith

Hollywood: Lomitas Productions, 1959. Vintage original film script, 11 x 8 1/2″ (28 x 22 cm.). Printed wrappers, mimeograph, brad bound, 173 pp. Light staining to wrappers, very slight chewing affecting extreme blank areas of a few final pages, overall very good+ or better. “Revised Screenplay” credited to Nathan E. Douglas (pseudonym for Nedrick Young) and Harold Jacob Smith, dated August 13, 1959. Sold with a spiral-bound album of fourteen (14) 7 x 10″ (18 x 26 cm.) black-and-white photos, all backed with heavy paper, outer glassine slightly worn, overall near fine.

The stage version of Inherit the Wind, co-authored by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee (also known for their stage adaptation of Auntie Mame) was a popularly successful example of what is called a drama of ideas, a genre associated more with European playwrights like George Bernard Shaw and Bertholt Brecht than with the American theater. In the case of Inherit the Wind, the ideas literally put on trial are Darwin’s theory of evolution — and the freedom to teach it — versus the tenets of fundamentalist religion.

Lawrence & Lee’s courtroom drama was based on an actual 1925 case, the so-called “Scopes Monkey Trial” (State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes), in which a high school teacher named Scopes was put on trial for teaching the theory of evolution in defiance of a state statute that forbid it. The case achieved national prominence due to the fact that Scopes was defended by famous civil rights attorney Clarence Darrow, and the prosecution team included three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan. In Lawrence & Lee’s fictional dramatization of the case, Clarence Darrow is renamed Henry Drummond (played in the film by Spencer Tracy), William Jennings Bryan is renamed Matthew Harrison Brady (played by Fredric March), the teacher Scopes is renamed Bertram T. Cates (Dick York). H. L. Mencken, the notoriously cynical journalist who covered the trial, is renamed E. K. Hornbeck (played in the film by Gene Kelly).

In addition to pitting science against religion, producer/director Stanley Kramer’s film version of Inherit the Wind gives us two opposing acting styles in the leading roles, pitting the “naturalism” of Spencer Tracy against the carefully constructed character acting of Fredric March (an actor, like Alec Guinness or Laurence Olivier, who liked to disappear into his roles). The movie is also noteworthy for its casting of Florence Eldridge, rarely seen on film since the 1930s, in the role of Mrs. Brady. Eldridge, who was married to Fredric March, was best known for her appearances opposite her husband on stage in plays like Long Day’s Journey Into Night and The Skin of Our Teeth.

The screenplay adaptation of Inherit the Wind was by Nedrick Young and Harold Jacob Smith, a pair who received the Academy Award two years earlier for their original screenplay of Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones (1958). Young, who was blacklisted throughout the 1950s for his alleged Communist leanings, used the pseudonym Nathan E. Douglas on the title page of this screenplay, but was properly credited as Nedrick Young on the released film.

The play takes place on an abstract set that shows the inside of the Hillsborough Courthouse and the plaza outside it simultaneously. It begins with a 13-year-old boy teasing a 12-year-old girl outside the courthouse with a worm he has picked up, “What’re yuh skeered of? You was a worm once.” The screenplay adaptation, on the other hand, begins with a pan down from the sky to a clock tower (It is 8:00 a.m.), and a trio of city officials emerging from the courthouse on their way to arrest Bertram Cates.

The next scene in the film script — not in the play — shows the city officials arresting Cates in his classroom as he begins to lecture his students on Darwin’s theory. The following scene in the film script — also not in the play — shows a meeting of the Chamber of Commerce discussing the pros and cons of starting a case that will bring national attention to their little Southern town.

Once defense attorney Drummond (the Spencer Tracy character) arrives in town, greeted by journalist Hornbeck, and the trial begins, the screenplay tracks the stage play quite closely. The courtroom scenes that are the heart of the play are reproduced in the screenplay and film almost verbatim. Yet the screenplay and film do not skimp on spectacle. The enthusiastic crowd that greets Brady in the town square, the parade of believers singing “Gimme That Old-Time Religion”, the carnival-like atmosphere outside the courthouse, the Reverend Brown’s outdoor prayer meeting, and the quasi-lynch mob that later gathers outside Cates’s jail cell help to make the story cinematic (all of these things are suggested abstractly in Lawrence & Lee’s play, but staged with great realistic verve in Stanley Kramer’s film version).

Because the screenplay is so long (173 pages) the biggest differences between the screenplay and film are a matter of cutting. The screenplay’s dialogue is trimmed whenever possible. Entire sequences are deleted. Among the sequences in the screenplay that are omitted from the film are:

(1) a scene of Hornbeck in his Baltimore newspaper office when he first hears about the case;

(2) a scene between Mrs. Brady and Brady in a hotel room where Mrs. Brady privately expresses her fear of the crowd’s fanaticism and Brady tells her, “Don’t worry, I can control them”;

(3) a scene following the trial verdict where Rachel Brown, the fiancée of the defendant, tells her father, the fundamentalist Reverend Brown, that she is moving out of his house;

(4) a scene following Brady’s collapse in the courtroom, where, in an addled state, of mind he begins reciting the speech he would have given if he had won the presidency — in the movie, he simply collapses, presumably from a stroke, and we don’t see him again, but learn in the next scene that he has died.

One difference between the play and the film that reviewers criticized occurs at the very end. At the conclusion of both the play and the screenplay, Drummond picks up the two books, the Bible and Darwin’s Origin of Species, weighs them in his hands, and places them side-by-side in his briefcase. In the movie, he places the Bible on top of Darwin before placing the two books in his briefcase, a gesture that some interpreted as a sop to the hardcore religionists who would have hated the film in any event.

Inherit the Wind is unmistakably a film by producer/director Stanley Kramer. It shares with virtually all of Kramer’s productions a focus on progressive social issues. Like Kramer’s production of The Caine Mutiny (Edward Dmytryk, 1954), it climaxes with the collapse of its chief antagonist (Bogart’s Captain Queeg in The Caine Mutiny, March’s Matthew Brady in Inherit the Wind) on the witness stand, followed by a scene where the defense counsel hero (Jose Ferrer in The Caine Mutiny, Spencer Tracy in Inherit the Wind) chastises one of his allies (Fred MacMurray in The Caine Mutiny, Gene Kelly in Inherit the Wind) for taking a cynical delight in the antagonist’s destruction. Similarly, in another Kramer courtroom film, Judgment at Nuremberg (Stanley Kramer, 1961), the chief defendant, a reluctant Nazi (played by Burt Lancaster), rebukes his attorney (Maximillian Schell) after the verdict for defending him so zealously. More than sixty years after their release, Stanley Kramer’s productions of Inherit the Wind, The Caine Mutiny and Judgment at Nuremberg are still revered as classic Hollywood courtroom dramas.

Out of stock

Related products

-

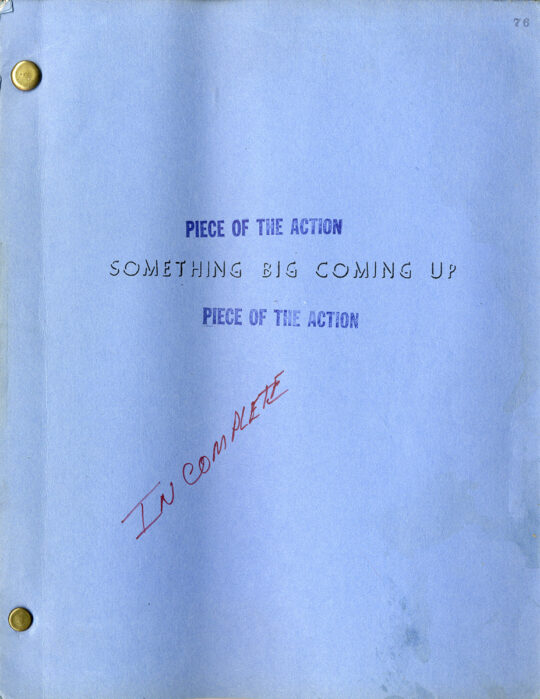

(African American film) A PIECE OF THE ACTION [working title: SOMETHING BIG COMING UP] (Nov 1, 1976) Film script

$750.00 Add to cart -

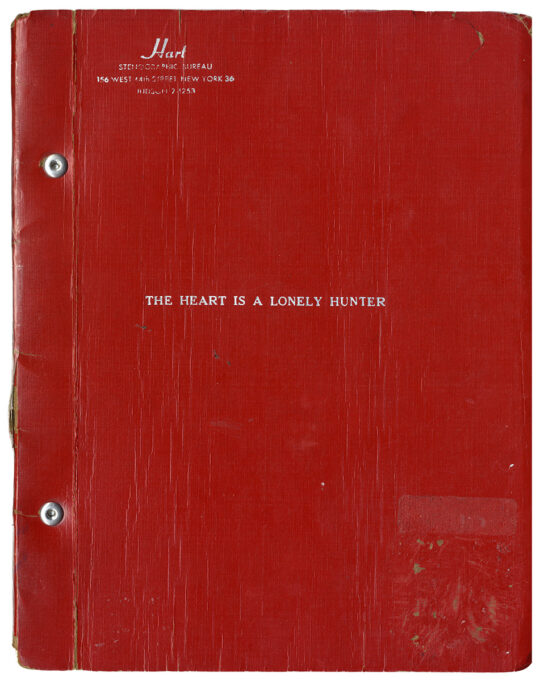

Carson McCullers (source) THE HEART IS A LONELY HUNTER (Aug 26, 1963) Film script by Thomas C. Ryan

$1,000.00 Add to cart -

![MON ONCLE D'AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French screenplay](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/MonOncleDAmeriqueFR-SCR_a-540x745.jpg)

Alain Resnais (director) MON ONCLE D’AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French film script

$2,500.00 Add to cart -

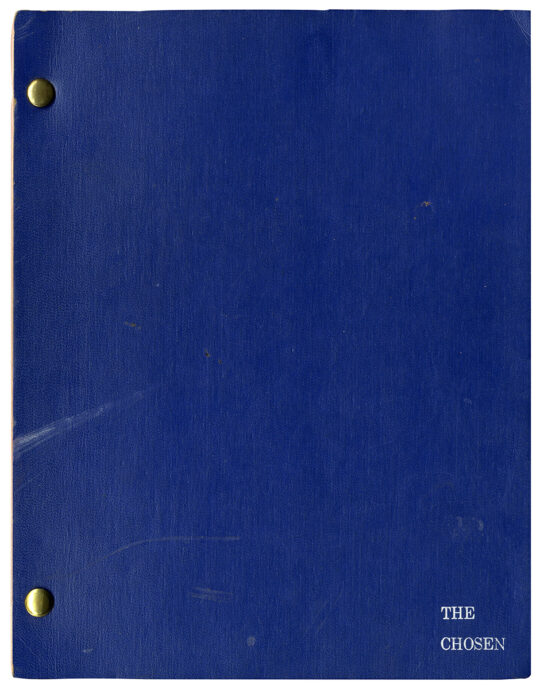

(Jewish American film) THE CHOSEN (Jul 25, 1980) Film script

$400.00 Add to cart

![Stanley Kramer (director), Scopes Trial (subject) INHERIT THE WIND (Aug 13, 1959) Revised draft film script by [Nedrick Young] and Harold Jacob Smith](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/InheritTheWindSCR_a.jpg)

![Stanley Kramer (director), Scopes Trial (subject) INHERIT THE WIND (Aug 13, 1959) Revised draft film script by [Nedrick Young] and Harold Jacob Smith - Image 2](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/InheritTheWindSCR_b.jpg)

![Stanley Kramer (director), Scopes Trial (subject) INHERIT THE WIND (Aug 13, 1959) Revised draft film script by [Nedrick Young] and Harold Jacob Smith - Image 3](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/InheritTheWindSCR_c.jpg)

![Stanley Kramer (director), Scopes Trial (subject) INHERIT THE WIND (Aug 13, 1959) Revised draft film script by [Nedrick Young] and Harold Jacob Smith - Image 4](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/InheritTheWindSCR_d.jpg)

![Stanley Kramer (director), Scopes Trial (subject) INHERIT THE WIND (Aug 13, 1959) Revised draft film script by [Nedrick Young] and Harold Jacob Smith - Image 5](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/InheritTheWindSCR_e.jpg)