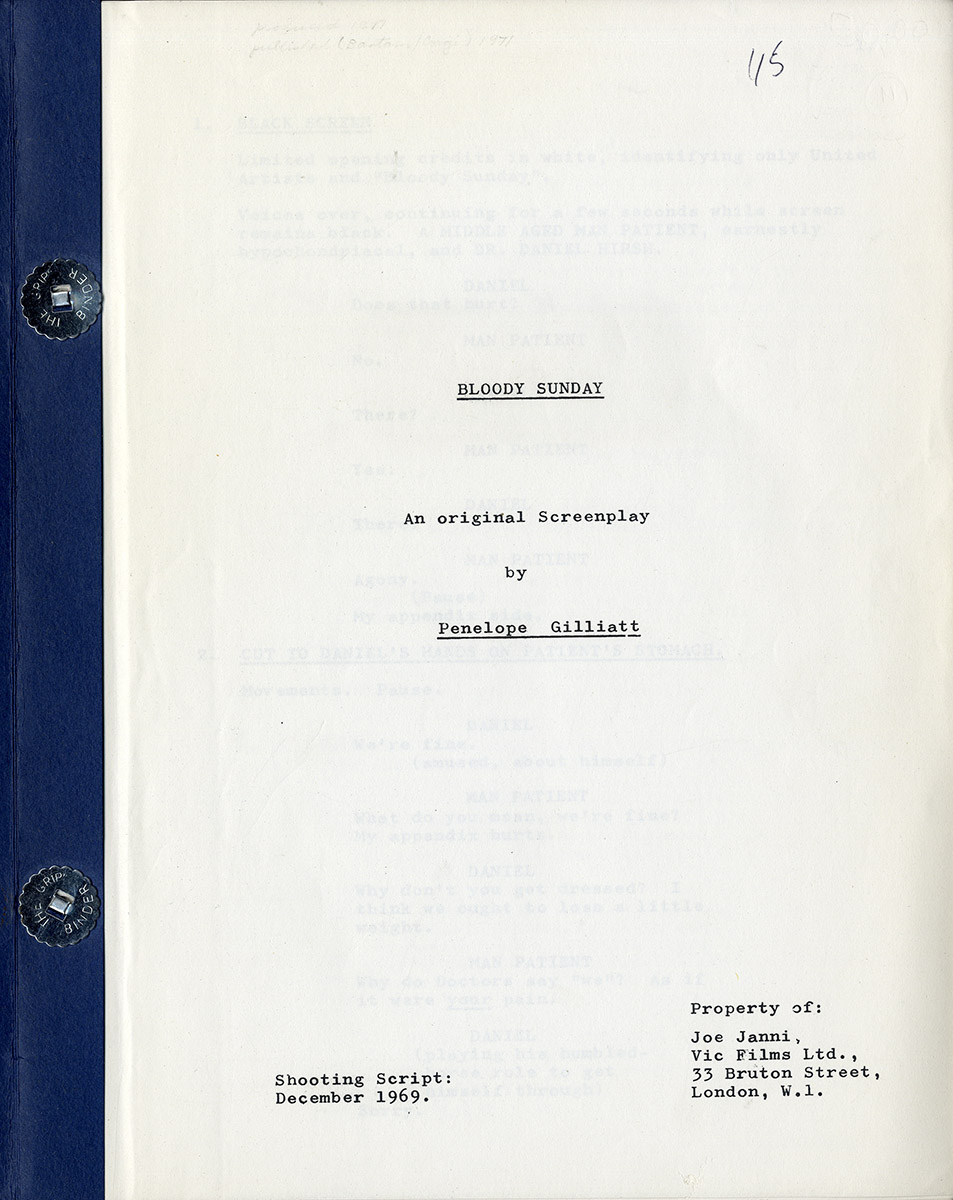

SUNDAY BLOODY SUNDAY (Dec 1969) Shooting script

London: Vic Films, 1969. Vintage original film script (under working title BLOODY SUNDAY), quarto, 133 pp. untitled stiff wrappers with die-cut title window. Title page dated December 1969. Mimeograph, internally brad-bound, slight yapping to fore edges, near fine in very good+ wrappers.

A landmark film in British gay film history.

SUNDAY BLOODY SUNDAY is the story of Daniel, a middle-aged doctor (Peter Finch), Alex, a career-woman in her mid-30s (Glenda Jackson), and Bob, the young artist who is a lover to both of them (Murray Head). It is a remarkable, accurately observed picture of what life in London was like for a particular class in the early 1970s, and what is most remarkable about it is its avoidance of melodrama and cliché. For example, although Daniel, the doctor played by Peter Finch, is homosexual, he is portrayed as neither flamboyant (the stereotypical comic queer) nor self-hating (the stereotypical tragicqueer). Here is how Gilliatt describes him in his first appearance.

“Daniel is a doctor in his early forties. Jewish. Clever, humorous face. He has a system of dispensing stoicism that helps him to keep at bay his own difficulties. His consulting room is part of his house, small and pleasant. Little jade elephants and ivory pigs on his desk. A silver photograph of his mother and father, playing two pianos and laughing, stands on a bookshelf behind him. A geodesic sculpture is visible through the window, set in a pretty walled garden with a rock pool.”

The sculpture referred to above turns out to be a creation of Bob, Daniel and Alex’s artist lover. Bob is a somewhat ambiguous character. Though we see some scenes through Daniel the doctor’s eyes, and other scenes through Alex the career-woman’s eyes, we rarely see anything through Bob’s eyes. Daniel and Alex are the story’s subjects; Bob, however sympathetic he may appear, is an object. The crisis at the center of the story–which is not really treated as a crisis–is that Bob wants to leave England for America. Daniel and Alex, though both in love with Bob, are more or less resigned to his decision, just as they long ago resigned themselves to sharing him.

In his filming of Penelope Gilliatt’s screenplay, director John Schlesinger trimmed it a bit–particularly the dialogue–but made few substantial changes. A couple of flashbacks for Daniel and Alex were eliminated. Many of the film’s visual ideas, for example, an inserted “detail of telephone exchange transmitting engaged number electronically” when Daniel calls his answering service, are indicated in the screenplay. Likewise, the musical idea of the “ironically sublime section of the quartet from COSI FAN TUTTE, used at moments through the film” is indicated in Gilliatt’s script.

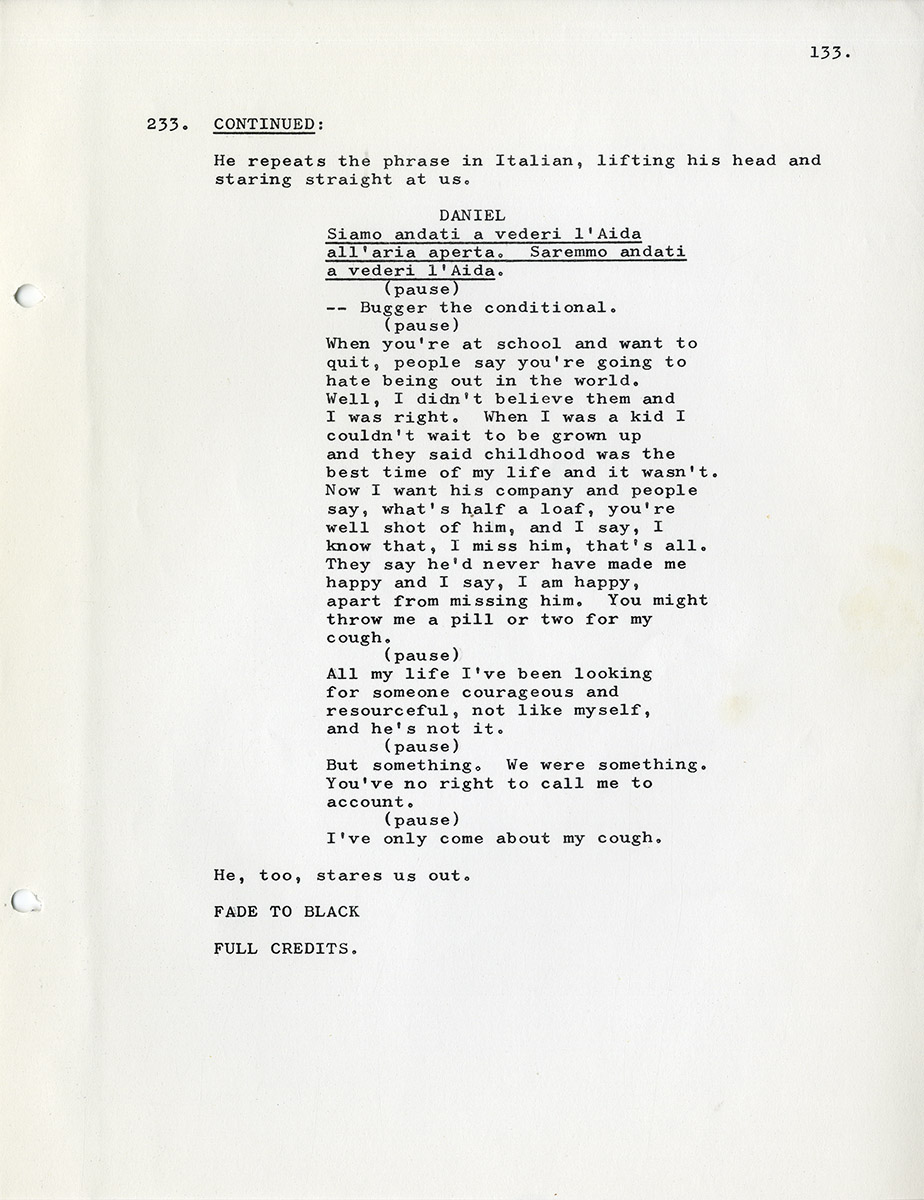

In one of the screenplay and film’s most poignant scenes, Daniel attends a Bar Mitzvah in a resplendent Orthodox Jewish Synagogue. The poignance derives in part from Daniel’s connection to an ancient tradition, and in part from Daniel’s sense of exclusion as a single gay man from the world of marriage and family. The screenplay and film end memorably with a monologue by Daniel addressed directly to the camera.

Not in WorldCat or AMPAS.

Russo, pp. 209-211: “One kiss exchanged between Head and Finch… [was] the first affectionate kiss on screen between two men that was not a device or a shock mechanism. It drew gasps from audiences wherever it played.” Porter and Prince, p.222: “A breakthrough in its matter-of-fact treatment of bisexuality.”

Out of stock

Related products

-

(African American film) CAR WASH (1976) Third draft film script by Joel Schumacher

$850.00 Add to cart -

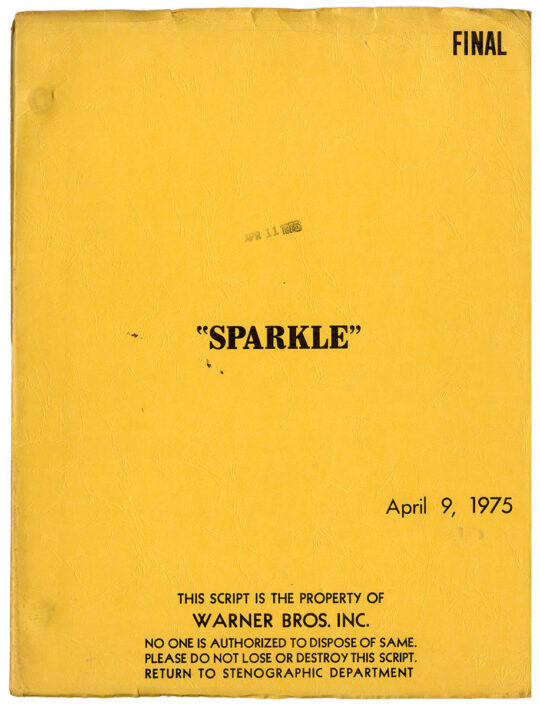

(Blaxploitation film) SPARKLE (Apr 9, 1975) Final Draft film script by Joel Schumacher

$750.00 Add to cart -

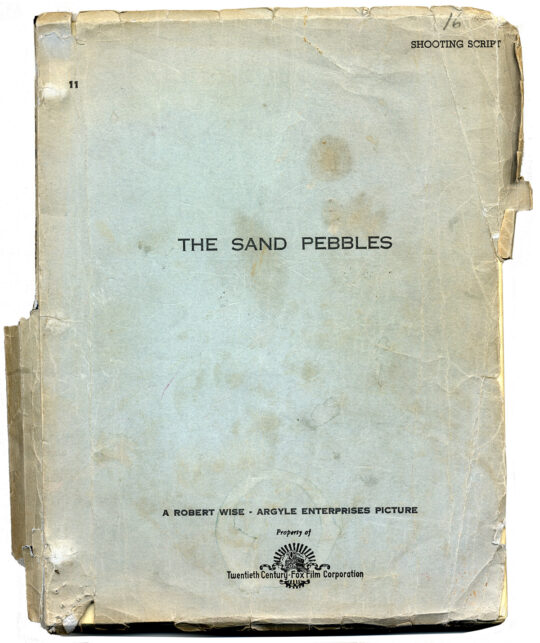

SAND PEBBLES, THE (Nov 1, 1965) Shooting script by Robert Anderson

$1,150.00 Add to cart -

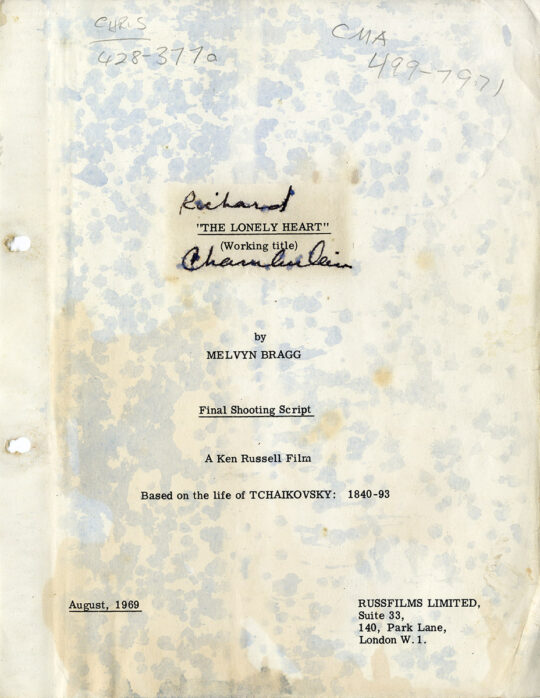

Ken Russell (director) THE MUSIC LOVERS [working title: THE LONELY HEART] (1969) Final shooting script

$3,000.00 Add to cart