FISHER KING, THE (1991) Revised Draft script by Richard LaGravenese dated Mar 16, 1990

Terry GIlliam (director) Vintage original revised draft script by Richard LaGravenese dated Mar. 16, 1990. Production company printed wrappers, brad bound, quarto, title hand-lettered on spine, light wear to yapped edges of wrappers, generally NEAR FINE in VERY GOOD+ wrappers, 123 pp.

THE FISHER KING was director Terry Gilliam’s sixth feature film, but the first from a screenplay that Gilliam did not write or co-write himself. It was the second produced script of Richard LaGravenese (born in Brooklyn, NY on October 30, 1959), an original work written on spec by LaGravenese in the late 1980s, and subsequently acquired by Hill/Obst Productions (producers Debra Hill and Linda Obst) who hired Gilliam to direct. The film, starring Jeff Bridges and Robin Williams, received several Academy Award nominations, including Best Supporting Actress for Mercedes Ruehl (which she won) and a Best Original Screenplay nomination for LaGravenese.

Today, LaGravenese is a well-established Hollywood screenwriter with more than 20 feature films and television projects to his credit (everything from THE BRIDGES OF MADISON COUNTY to THE HORSE WHISPERER to the television feature BEHIND THE CANDELABRA), five of which he also directed (LIVING OUT LOUD, FREEDOM WRITERS, P.S. I LOVE YOU, BEAUTIFUL CREATURES, and THE LAST FIVE YEARS). Although there is substantial variety to LaGravenese’s work, one common factor that stands out is the creation of strong roles for women.

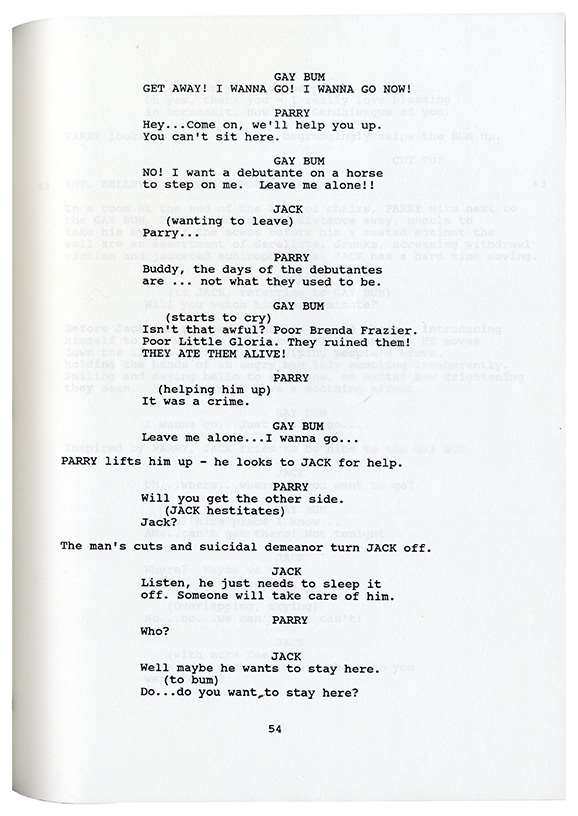

Regardless, the central relationship in THE FISHER KING is a “bromance” between disenchanted shock jock Jack Lucas (Bridges) and a traumatized homeless schizophrenic man, Parry (Robin Williams). The two important women in the film, Anne (Ruehl) and Lydia (Amanda Plummer), are basically supporting players, notwithstanding the richness of their characterizations (maybe the best film roles these two fine actresses ever had the opportunity to play). There is one more important human character, a gay homeless man played by Michael Jeter, and then there is the film’s location, New York City, which is a character in its own right.

The story’s mythological spine is the legend of the Fisher King, the ruler of a wasteland, dying like he is (the land and its ruler are inextricably linked), and which can only be restored to fertility and health through the bravery of a knight who wields the Holy Grail, retrieved from a haunted chapel known as Chapel Perilous. (See, Sir James Frazier’s classic anthropological study, “The Golden Bough”). The same myth also provides the background and inspiration for T.S. Eliot’s seminal modernist poem, “The Wasteland.”

Though not written or conceived by Gilliam, THE FISHER KING turns on a dichotomy found in many of Gilliam’s films, the conflict between a protagonist’s rich interior fantasy life and grim reality. (See, for example, BRAZIL, THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN, and Gilliam’s most recent project, THE MAN WHO KILLED DON QUIXOTE.) Many of Gilliam’s films also involve quests, often for some kind of grail-like magical object, the most obvious example being MONTY PYTHON AND THE HOLY GRAIL, or — in the case of 12 MONKEYS — the needle-in-a-haystack search for a particular moment in time. In THE FISHER KING, Jack’s quest to heal Parry is also fundamentally a quest to heal or redeem Jack himself after one of his flippant on-the-air remarks triggers a disturbed man to commit a mass nightclub shooting, a shooting that results in the death of Parry’s wife and Parry’s retreat into psychosis.

Did we mention this film is a comedy? A “bromantic” comedy perhaps, but one with tragedy, madness, and hallucination at its heart.

This particular draft of LaGravenese’s screenplay is most likely not the final shooting script, but something very close to it (particularly because its date of March 16, 1990 was just two months before shooting commenced on May 21.) It incorporates director Gilliam’s one admitted contribution to the story, the memorable fantasy sequence filmed in Grand Central Station where all the commuters suddenly pair off and start dancing with each other to the tune of a waltz.

In the completed film, Jack’s opening monologue to his radio listeners has been streamlined and polished. When a caller exclaims, “You’re a pig, Jack!” she tells us all we need to know about his character. The dialogue in the rest of the film has been similarly trimmed, polished or, in some cases, embellished. (Actor/comedian Robin Williams was known for his physical and vocal improvisations, and surely some of those improvisations made it into the final film).

Some of the changes between script and screen had to do with the film’s use of music — much more important in the film than you would realize from reading the screenplay. In the film, Jack the D.J. is introduced with the song “Hit the road, Jack” played over a black screen (this is the opening shot). In the screenplay, the homeless gay man played by Michael Jeter (credited in the film as “Homeless Cabaret Singer”) has an obsession with the musical CABARET. In the film, his obsession is with the musical GYPSY, which leads to the one of the film’s most successfully realized comic set pieces, when he shows up at Lydia’s office wearing a spangled red dress and high heels, carrying a bouquet of yellow balloons, and begins belting out in the style of Ethel Merman, “I had a dreeeaam. A dream about you, Lydia!!” Parry is associated with the song, “I like New York in June, how about you?” which we hear several times, including over the shot of fireworks above Central Park that concludes the film.

Some short sequences in the screenplay are omitted altogether, e.g., a scene where Parry defends his turf against a pair of black teenage hoods.

Though released in 1991, THE FISHER KING is very much a product of the 1980s, a work that, beneath its comedy, is pointedly critical of the materialism and narcissism of the Reagan era with a corresponding sympathy for the homeless and others who were left behind by that era.

Out of stock

Related products

-

DRESS GRAY (Mar 6, 1981) Second revision script by Gore Vidal

$500.00 Add to cart -

(Jewish American film) THE CHOSEN (Jul 25, 1980) Film script

$400.00 Add to cart -

Sidney Lumet (director) PRINCE OF THE CITY (Jan 1980) Final Draft film script

$950.00 Add to cart -

![(Blaxploitation film) BLACK BELT JONES [1974] Film script by Oscar Williams](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/BlackBeltJonesSCR_a-540x693.jpg)

(Blaxploitation film) BLACK BELT JONES [1974] Film script by Oscar Williams

$750.00 Add to cart