LEGEND OF LYLAH CLARE, THE (May 1, 1967) Screenplay by Hugo Butler [and] Jean Rouverol

[With most pages revisions on blue paper dated 6/12/67] Brad bound, mimeo, 138 pp. [with a final page not present, almost certainly because Aldrich had something else in mind — see below]. There is some minor wear to front and back pages, a few of which also have marginal stains, overall very good.

THE LEGEND OF LYLAH CLARE was originally a 1962 television drama written by Edward DeBlasio and Robert Thom (WILD IN THE STREETS, BLOODY MAMA) that starred Tuesday Weld in the “dual” role of Elsa Brinkmann/Lylah Clare. Elsa Brinkmann is a novice actress who at times believes she is possessed — or may actually be possessed — by the spirit of legendary European star Lylah Clare. In the 1968 movie, she is played by Kim Novak. The story’s other principal character is the film director Lewis Zarkan (played in the movie by Peter Finch) who discovered and made a star out of Lylah Clare in the 1930s (much as Josef von Sternberg discovered and made a star out of Marlene Dietrich), and who wants to do the same thing for Elsa, a virtual double of his former lover Lylah, in the present.

LYLAH CLARE is an odd, occasionally awkward, amalgamation of genres. On the one hand, it’s a horror mystery thriller about possible reincarnation and possession. On the other hand, it’s a savage satire of Hollywood and media in general. For director Robert Aldrich, who had previously attacked Hollywood in THE BIG KNIFE and WHATEVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE, the Hollywood satire angle was raw meat. (He would skewer show business and the media once again in a subsequent film, THE KILLING OF SISTER GEORGE.) Engaged as Aldrich was by the satire and sex-and-violence aspects of the story, the mystical reincarnation angle appeared to interest him somewhat less.

The movie makes more than one veiled reference to actual Hollywood personae — not just Dietrich and von Sternberg, but the crass producer Barney Sheehan (Ernest Borgnine) appears to be modeled on Columbia studio executive Harry Cohn (note the similarity of the names), while the vicious gossip columnist Molly Luther (Coral Browne) combines aspects of Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons. The movie even appears to reference the career of its star Kim Novak, not only the way Novak’s career and image were shaped by ultra-controlling studio head Harry Cohn, but also the dual role she previously played in Alfred Hitchcock’s VERTIGO.

This screenplay adaptation was written by Hugo Butler and Jean Rouverol, former blacklistees who were married to each other. Butler is best remembered for the screenplays he wrote or co-wrote for director Joseph Losey (another blacklistee), THE PROWLER, THE BIG NIGHT, and EVA. He also wrote the screenplays for Luis Buñuel’s two English-language films, ROBINSON CRUSOE and THE YOUNG ONE, and worked on three prior films for director Aldrich, WORLD FOR RANSOM, AUTUMN LEAVES, and SODOM AND GOMORRAH.

Jean Rouverol, a former actress (IT’S A GIFT, STAGE DOOR), collaborated with her husband on the screenplay of Aldrich’s Joan Crawford vehicle, AUTUMN LEAVES, and may be best known for her screenplay of THE MIRACLE, starring Carroll Baker.

While THE LEGEND OF LYLAH CLARE was derided by many at the time of its release as trashy or “camp,” an impassioned minority of auteurists now consider it to be one of Aldrich’s masterpieces.

There were a number of significant changes and edits between this screenplay draft and the completed film, notably the sequencing of scenes at the beginning, and the way the film ends.

The screenplay begins with:

- A scene of Elsa sleeping alone in her room surrounded by images of Lylah Clare in the form of books, magazines, and photographs (she is having a nightmare).

- A sequence of Elsa strolling down Hollywood Boulevard looking at the stars on the sidewalks, and paying particular attention to the handprints and footprints of Lylah Clare outside the Grauman’s Chinese Theater.

- A scene in director Zarkan’s study with Zarkan and agent Bart Langner (Milton Selzer) who reveals that he has cancer, that before he dies he wants to produce a film about Lylah Clare with Zarkan directing, and that he has discovered the perfect girl to play her. We also meet Zarkan’s exotic and sexually ambiguous right-hand woman Rosella (Rosella Falk).

- A scene with agent Langner and his wife at their home, projecting for his discovery, Elsa, a slide show pertaining to the life of Lylah Clare.The film, on the other hand, begins with the slide show, which functions like the newsreel in CITIZEN KANE, telling the audience everything it needs to know about Lylah before the story proper begins.

- The sequence of Elsa strolling down Hollywood Boulevard, which in the film is also the credit sequence.

- The scene in Zarkan’s study with the agent.

- The scene of Elsa having a nightmare at home surrounded by images of Lylah, only in the film, unlike the screenplay, this scene is underscored with the disembodied voice of Lylah on the soundtrack, ranting in her native German.

The script’s ending is missing what would have been its last page, almost certainly indicating that, as of this draft the filmmakers hadn’t decided exactly how they wanted the film to conclude (or wanted to keep it a secret). The script draft ends with Zarkan and others filing out of Grauman’s Chinese Theater after the premiere of Zarkan’s film-within-the-film and being asked by a television M.C. how they feel about the tragic death of Elsa, the film’s star. The M.C.’s interviews are intercut with shots of Rosella holding a gun in her hand that she clearly intends to use on Zarkan once he arrives home, as vengeance for Elsa’s death.

The film ends with one of the most radical endings ever attached to a Hollywood narrative film. The interviews with the M.C. are still there, but they have been substantially rewritten. The shots of Rosella waiting at home with the gun are still there, although we never see her use it. But suddenly the M.C. announces, “And now a word from our sponsor,” and we cut to a commercial for “Barkwell Dog Food.” The commercial begins innocently enough with a woman opening a can of dog food, and shots of dogs running into the kitchen eager to be fed. But more and more dogs arrive, hungrier, and more frenzied, and we see close-ups of their snarling faces. The film’s haunting final shot is a tight freeze-frame close-up of one of the dogs, fangs savagely bared, expressing literally Aldrich’s view of Hollywood as a world of dog-eat-dog.

LYLAH CLARE has more LGBTQ characters than any film Aldrich had made to date. Kim Novak’s Elsa (when in her Lylah Clare persona) and Zarkan’s right-hand woman Rosella are both bisexual, the latter in love with the former. The person who we see in flashbacks, killed by Lylah on the staircase, turns out to be a woman in drag. Gossip columnist Molly Luther is never seen in public without her two gay male attendants.

Finally, one should note the movie’s autobiographical aspect. Elsa dies in the film after completing a difficult trapeze stunt and director Zarkan asks her to do it “one more time, for protection.” In a previous Aldrich film, THE FLIGHT OF THE PHOENIX (1965), a stunt pilot, Paul Mantz, died after completing a difficult flying stunt and Aldrich asked him to do it “one more time, for protection.” This part of LYLAH CLARE (not in the screenplay draft) was plainly Aldrich’s mea culpa, and adds additional layers of bitterness and melancholy to the completed project.

Out of stock

Related products

-

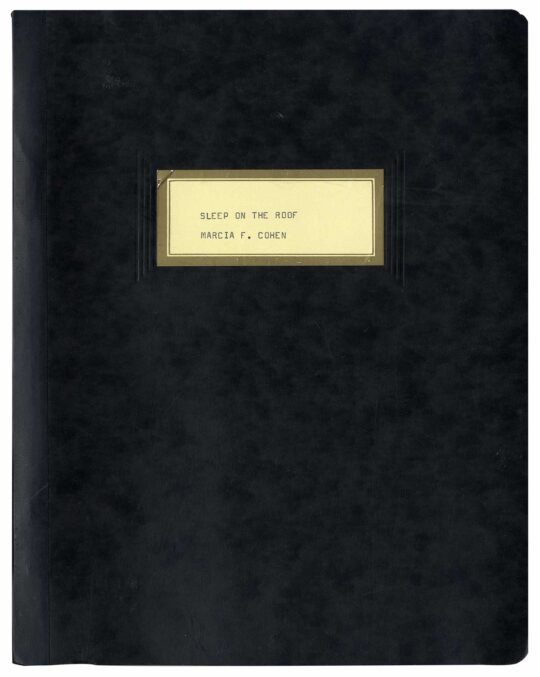

SLEEP ON THE ROOF (1967) Unproduced script based on the life of Margaret Sanger

$500.00 Add to cart -

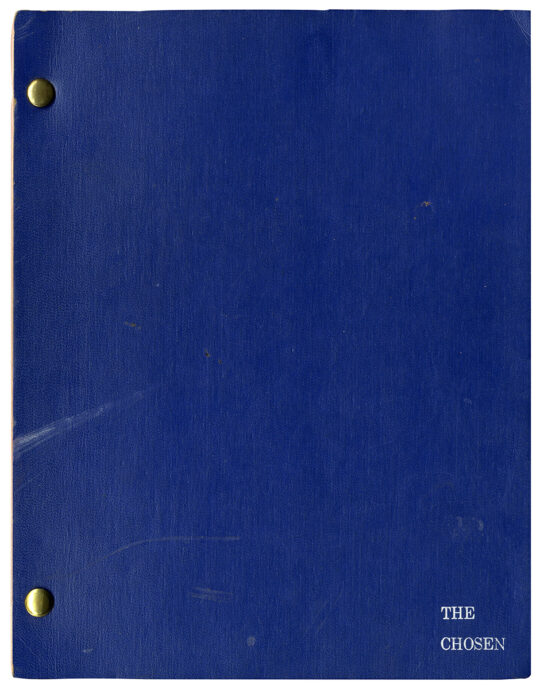

(Jewish American film) THE CHOSEN (Jul 25, 1980) Film script

$400.00 Add to cart -

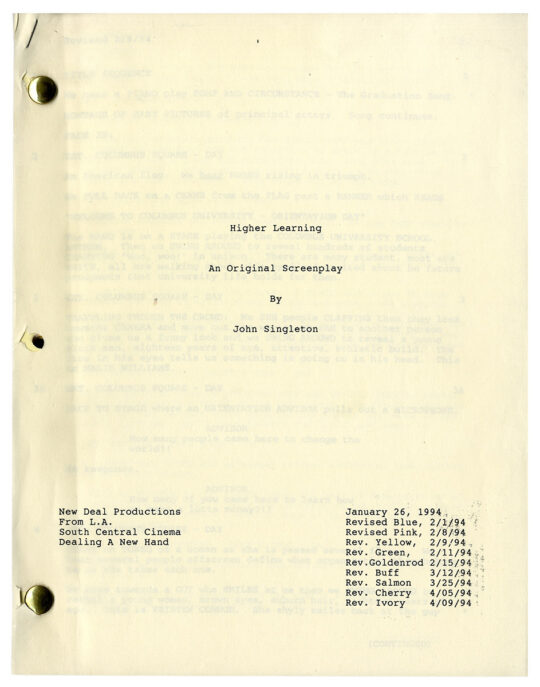

John Singleton (writer, director) HIGHER LEARNING (Jan 26, 1994) Rainbow film script

$500.00 Add to cart -

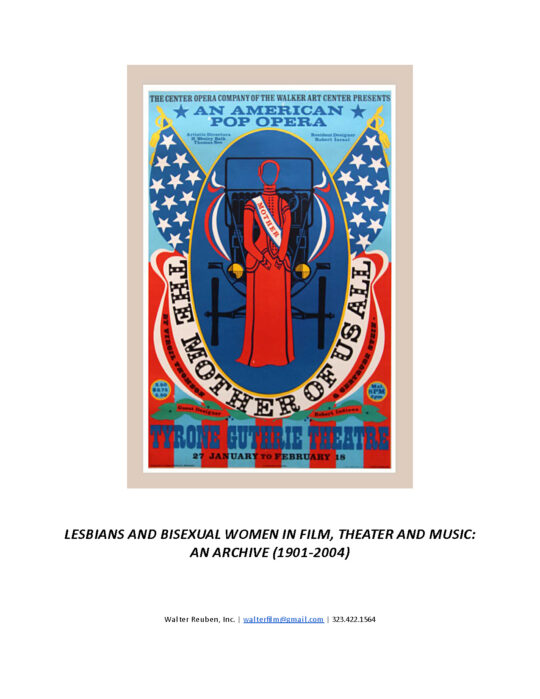

LESBIANS AND BISEXUAL WOMEN IN FILM, THEATER & MUSIC (1901-2004) Archive

$40,000.00 Add to cart

![LEGEND OF LYLAH CLARE, THE (May 1, 1967) Screenplay by Hugo Butler [and] Jean Rouverol](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/LYLAH1-scaled.jpg)

![LEGEND OF LYLAH CLARE, THE (May 1, 1967) Screenplay by Hugo Butler [and] Jean Rouverol - Image 2](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/LYLAH2-scaled.jpg)

![LEGEND OF LYLAH CLARE, THE (May 1, 1967) Screenplay by Hugo Butler [and] Jean Rouverol - Image 3](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/LYLAH3-scaled.jpg)