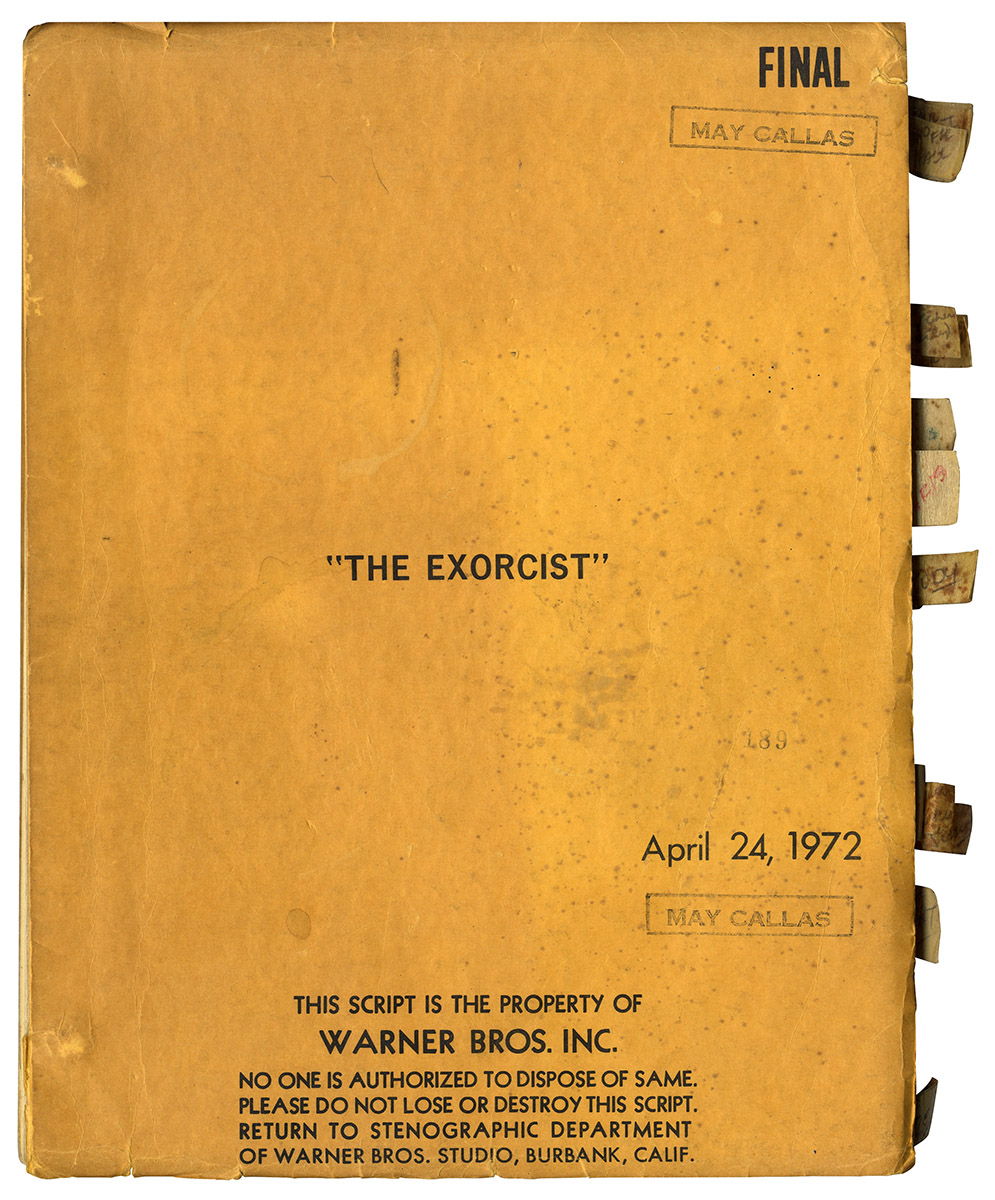

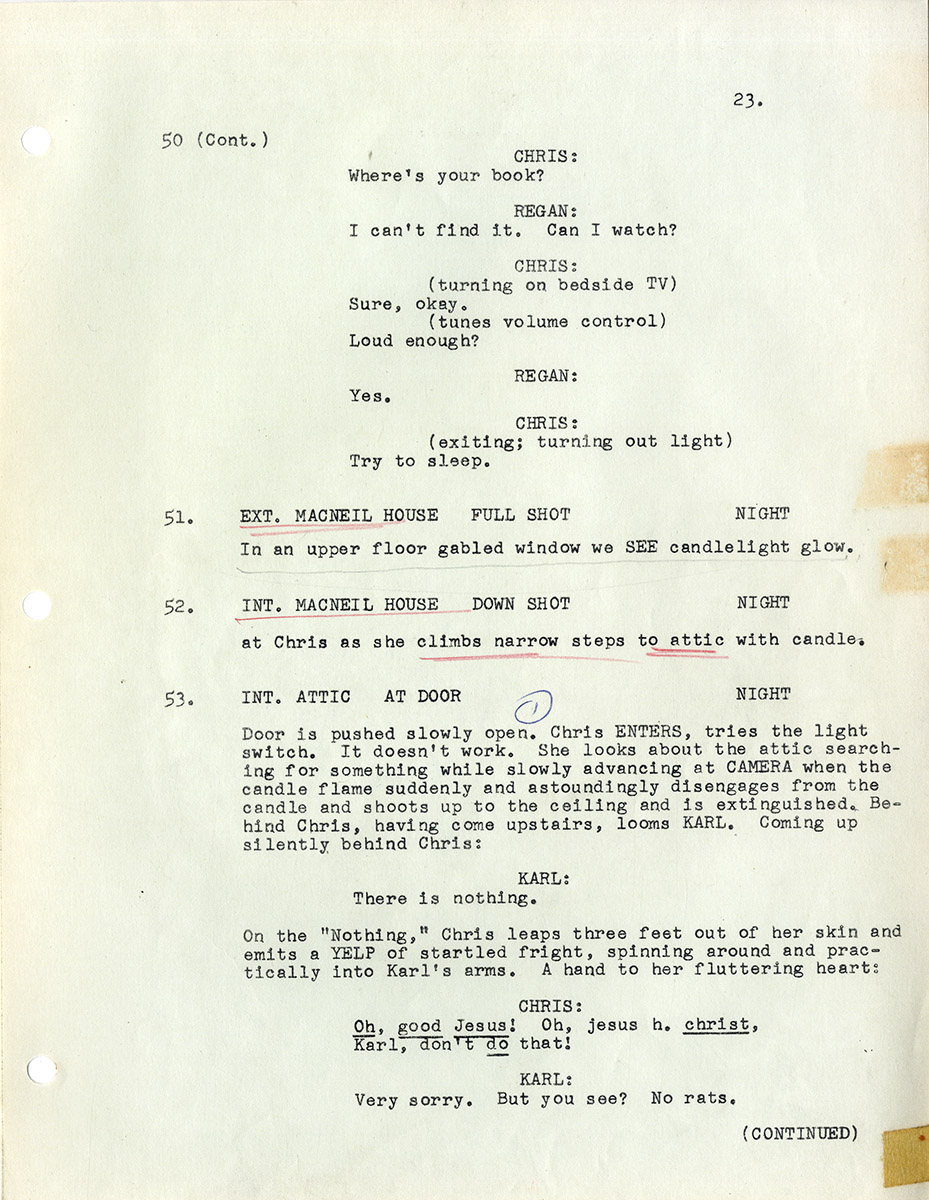

William Friedkin (director) THE EXORCIST (Apr 24, 1972) Revised final film script

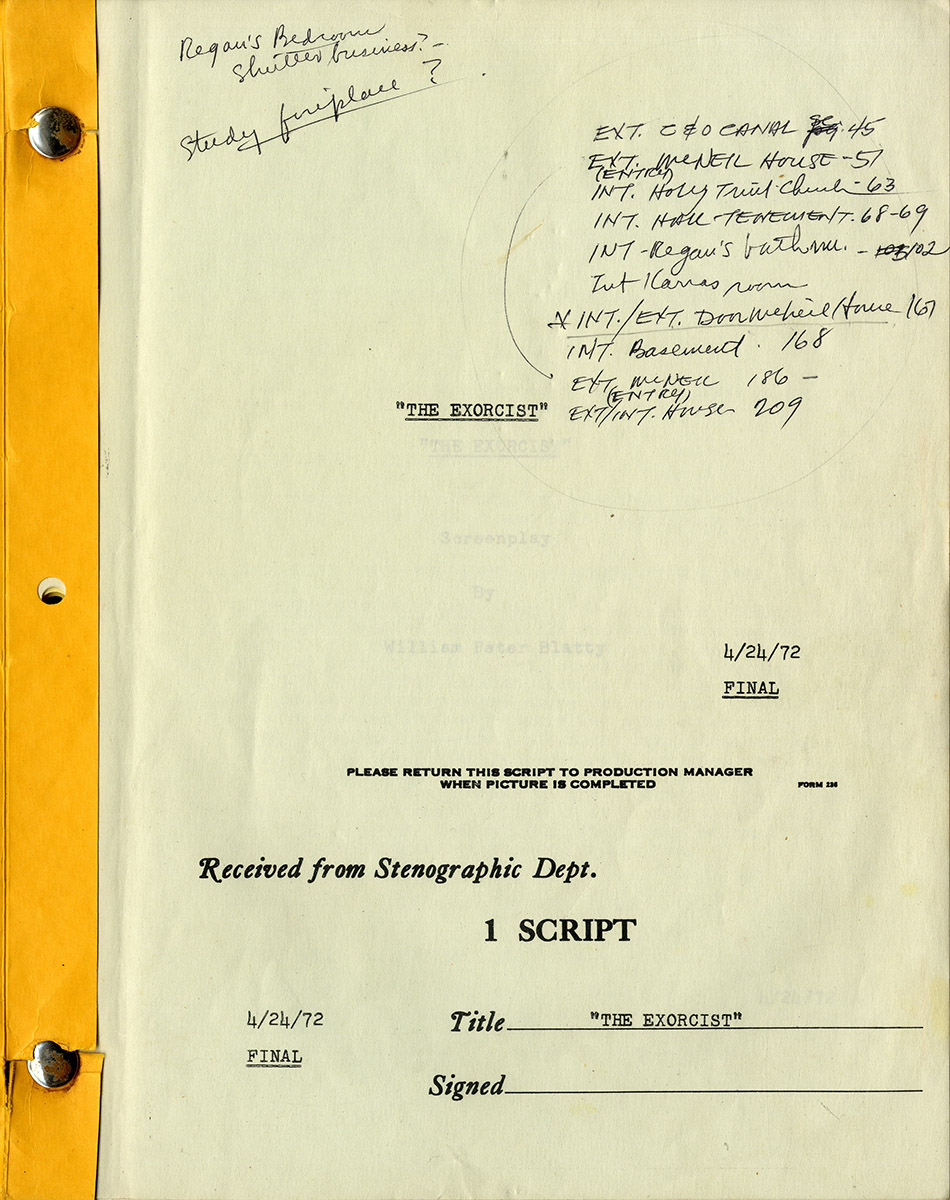

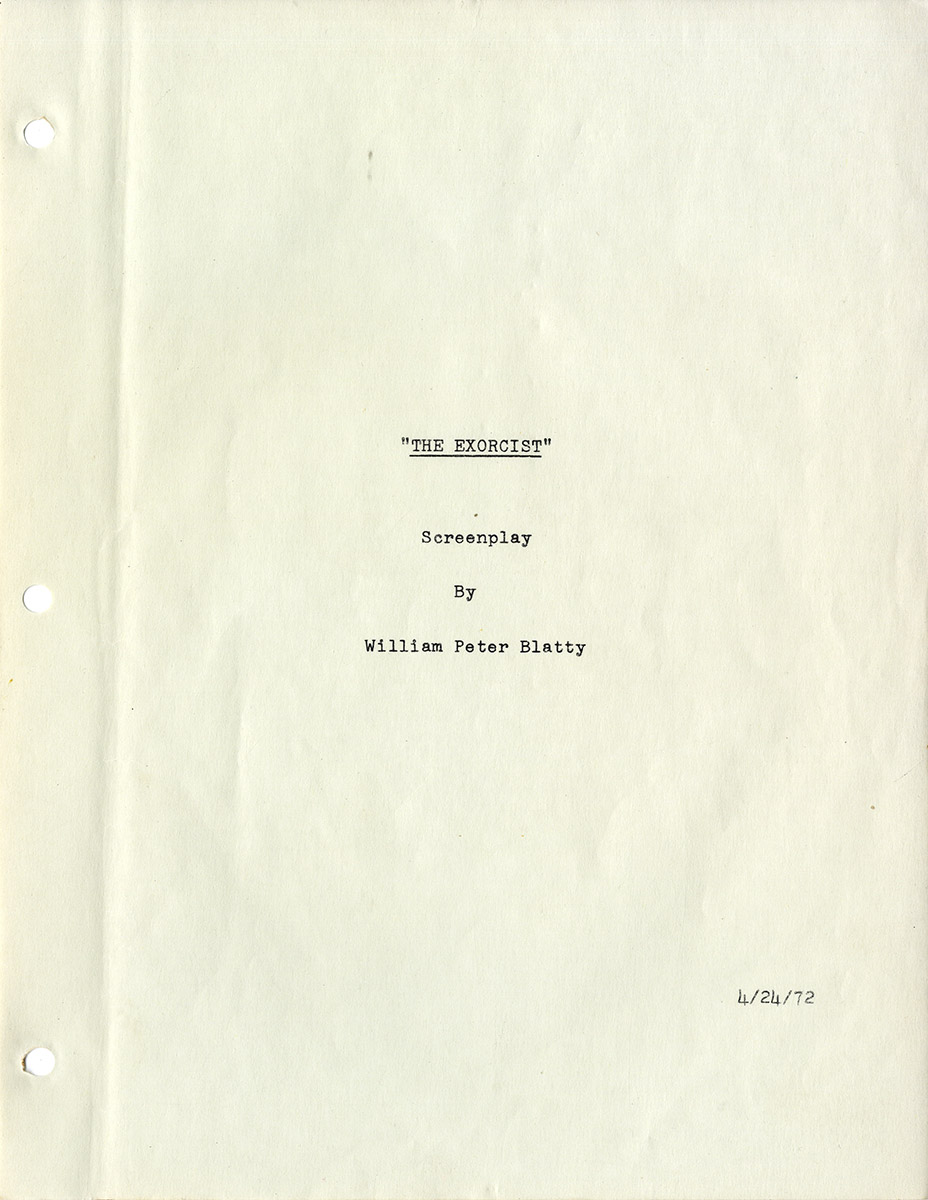

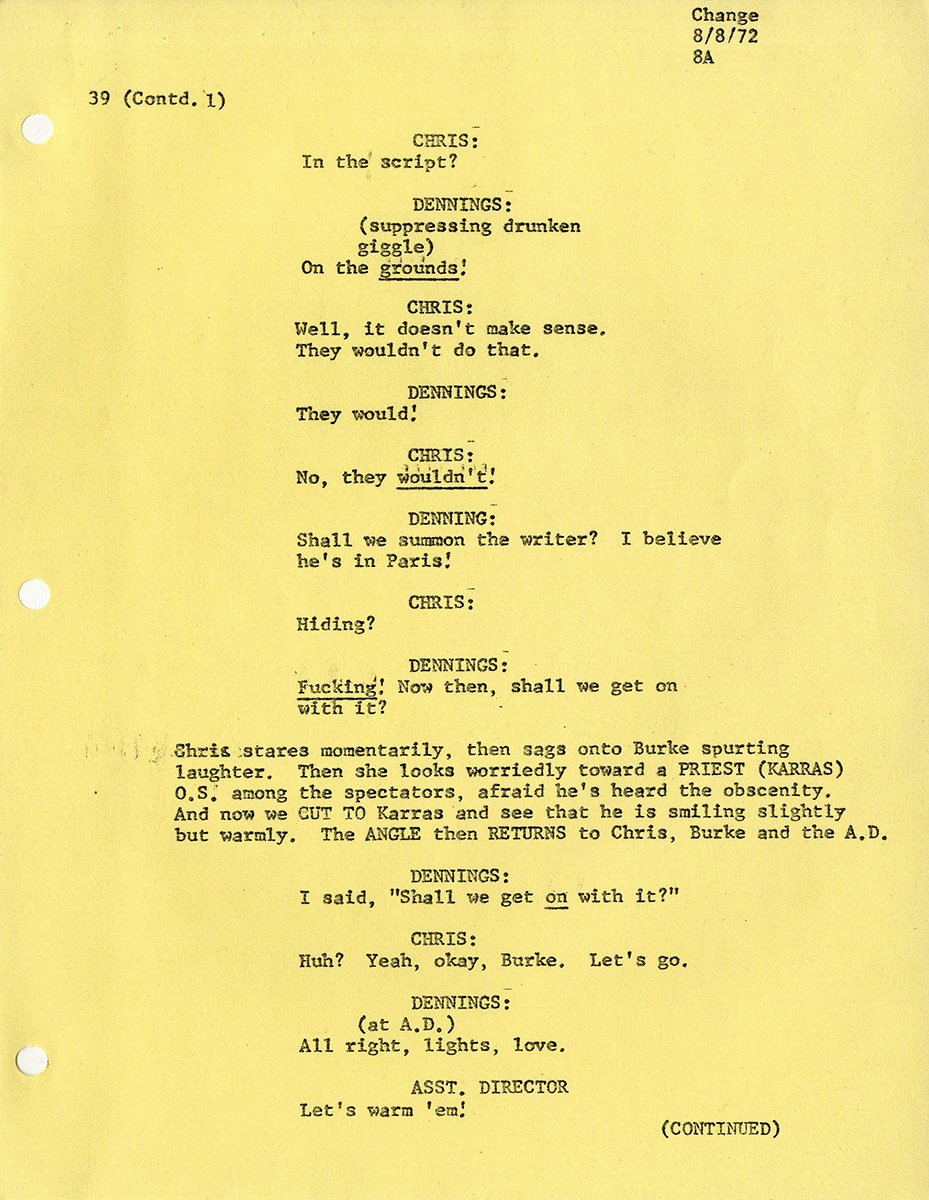

[Burbank, CA]: Warner Brothers, 1972. Vintage original film script, 11 x 8 1/2″ (28 x 22 cm.), 133 pp. Printed studio wrappers, brad bound. Title page credits screenplay to William Peter Blatty with a date of 4/24/72 noted as FINAL. Mimeographed, but with many pages of revisions printed in photocopy on yellow paper, dated up through 8/15/72. Light spotting to covers, a few pages with MS notations, near fine in very good+ wrappers.

The Exorcist was a groundbreaking motion picture in several respects. Following in the wake of Rosemary’s Baby (1968), which was also based on a best-selling novel, it was produced and marketed not just as a horror movie but as a big-budget “event film” and eventually surpassed My Fair Lady as Warner Brothers’ most financially successful film to that date. It became the first horror movie to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture, and its producer/screenwriter, William Peter Blatty, won the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. Moreover, The Exorcist went much further than any of its A-budget horror film predecessors in terms of shock value, assaulting the audience with an unending torrent of bodily fluids, verbal obscenities and horrifyingly blasphemous imagery, all for the purpose, according to its producer/writer, of bringing the viewer closer to God.

The film’s producer and screenwriter, William Peter Blatty, was previously known as a scripter of comedies like What Did You Do in the War, Daddy? and A Shot in the Dark. Producer Blatty personally chose the movie’s director, William Friedkin, who had just won the Academy Award for his direction of the 1971 neo-noir action film The French Connection.

Much of the film’s interest lies in the tension between its devout Catholic screenwriter Blatty, who wanted to make a clear theological statement, and its secularly Jewish director Friedkin, whose primary interest was putting his audience through a visceral experience (like the car chase in The French Connection) and letting viewers interpret what they saw for themselves.

As virtually every film buff knows, The Exorcist is a brilliantly constructed story about a 12-year-old girl, Regan MacNeil, who is possessed by a demon. As the novel and screenplay make clear, it is a very specific demon from the region of Assyria whose name is Pazuzu. The movie more ambiguously identifies the possessing entity simply as the devil. Opposed to the demon are two Catholic priests: a young man, Father Karras (played in the film by Jason Miller) who is also a trained psychiatrist, and an older man, Father Merrin (Max von Sydow) who specializes in archaeology. The demon is ultimately defeated, but neither priest survives the ordeal. The movie in its original release version ended abruptly with the death of Father Karras, leaving the audience in a state of shock. The screenplay, and the restored version of the film released 25 years later, include an upbeat coda, truer to the writer’s intention in which it is firmly established that good has prevailed.

Much of the screenplay and film’s strength lies in the way it is anchored in reality, for example its use of actual locations in the Georgetown district of Washington, D.C. The character of Regan’s mother, a film actress, was closely based on real-life actress Shirley MacLaine; and her director friend who gets killed in the screenplay’s second act was based on real-life director J. Lee Thompson. Virtually everything written in the screenplay was actually filmed, though several sequences were discarded in the cutting room, only to resurface 25 years later in the restored version.

Aside from discarded sequences, there are few substantial differences between Blatty’s screenplay and the released film. Notably missing from the screenplay is the climax of the movie’s exorcism sequence with the two priests jointly chanting “The power of Christ compels you!” In the film, but not in the screenplay, the possessed child is able to speak in Latin and French.

The biggest difference is in the movie’s mostly wordless prologue — only 4 pages in the screenplay, 9 and 1/2 minutes as filmed — showing Father Merrin at an archaeological dig in Northern Iraq. In the screenplay, Father Merrin finds a stone amulet head of the demon Pazuzu among recently unearthed artifacts displayed on a table. In the movie, Father Merrin witnesses for himself the unearthing of various artifacts from the ancient world, including the amulet demon head and — in a significant departure from the screenplay — they also find a St. Joseph’s medal buried alongside it. While this is clearly a temporal impossibility, it signifies the eternal co-existence of good and evil. The St. Joseph’s medal also appears (for the first time in the screenplay) at the story’s conclusion when it is found in Regan’s bedroom after the exorcism is over.

In terms of subtext, the screenplay and film capitalize on Conservative America’s fear of the Younger Generation during the era of Woodstock, hippies and the Vietnam War protests. This fear of the child also lay behind the horror of 1968’s Rosemary’s Baby and the zombie daughter who kills her parents in Romero’s 1971 Night of the Living Dead. The Exorcist screenplay makes the connection explicit by including a scene where Regan’s actress mother is seen shooting a film, Crash Course, about campus protests.

NOTE: This particular copy of the screenplay has numerous tags and occasional notations in pencil referring to set locations and props (bed, television set) indicating it most likely belonged to someone in the set decoration or prop department. The name stamped on the script’s cover, May Callas, is that of someone who worked in the art department of numerous motion pictures, including 1981’s Ragtime.

Out of stock

Related products

-

![MON ONCLE D'AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French screenplay](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/MonOncleDAmeriqueFR-SCR_a-540x745.jpg)

Alain Resnais (director) MON ONCLE D’AMÉRIQUE [MY AMERICAN UNCLE] (1979) French film script

$2,500.00 Add to cart -

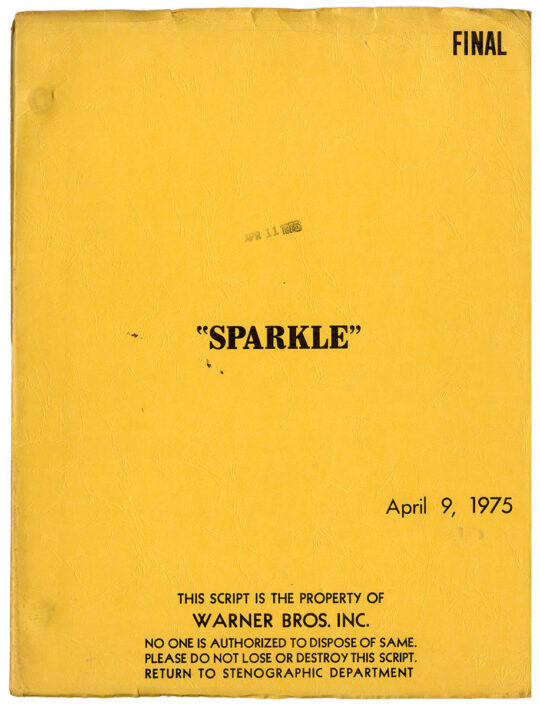

(Blaxploitation film) SPARKLE (Apr 9, 1975) Final Draft film script by Joel Schumacher

$750.00 Add to cart -

LOOT (ca. Sep 1969) Final Draft screenplay

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

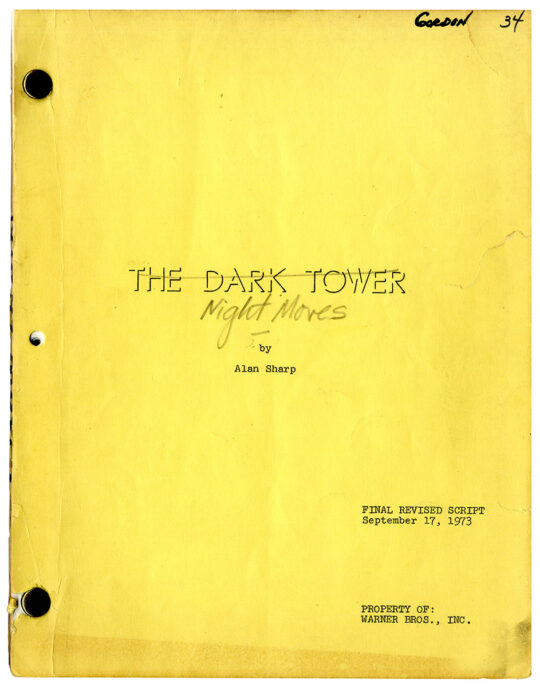

Arthur Penn (director) NIGHT MOVES [working title: THE DARK TOWER] (Sep 17, 1973) Final revised film script

$2,000.00 Add to cart