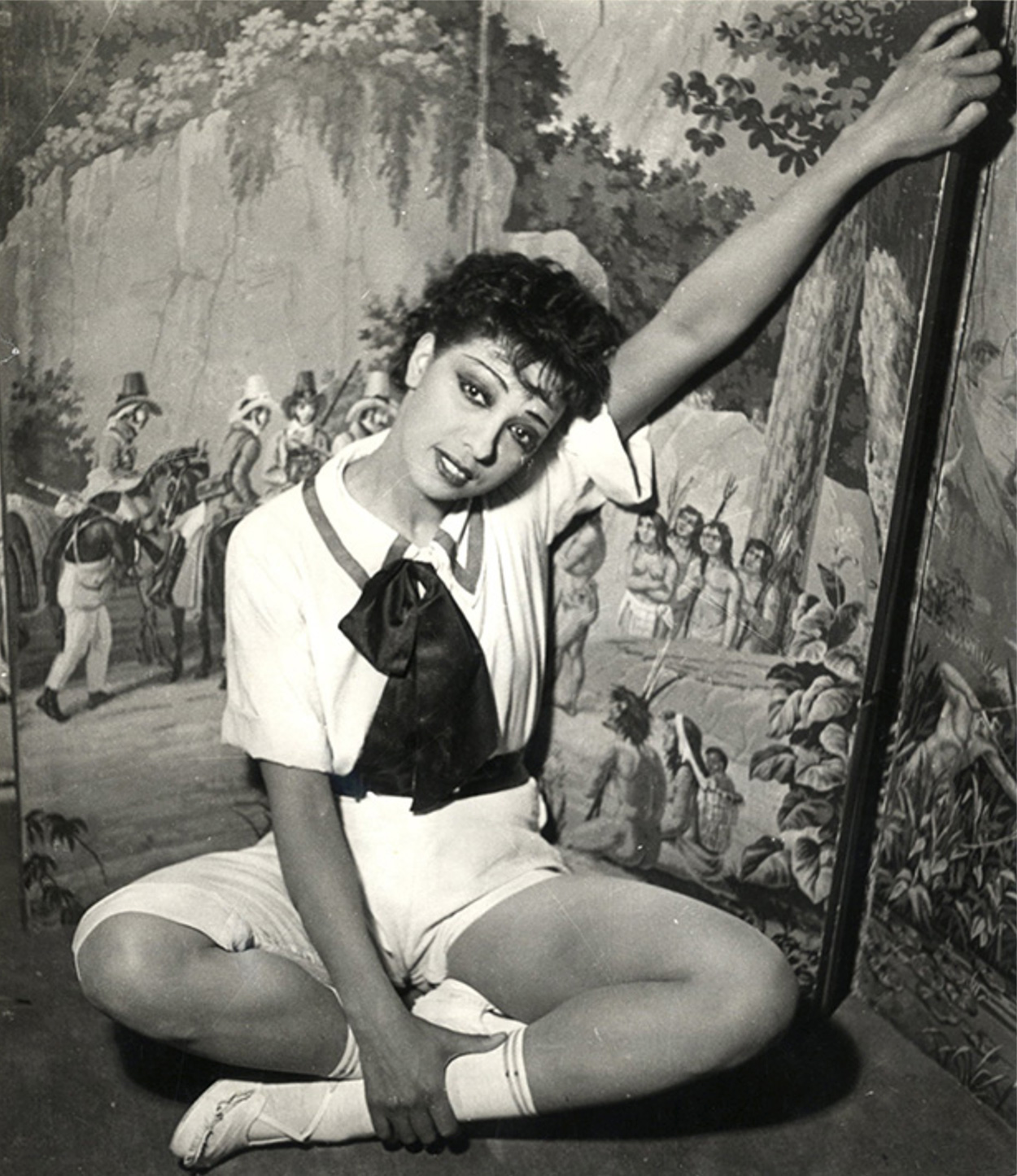

Josephine Baker – An African-American in Paris

THE ABOVE PHOTOGRAPH: Paris: Henri Manuel, (1927). Vintage original 9 1/2 x 7″ (24 x 18 cm.) black-and-white print still photo, France. Photo has on verso a stamp of photographer Henri Manuel and a 1927 date stamp, NEAR FINE.

Joséphine Baker (born Freda Josephine McDonald; naturalized French Joséphine Baker; June 3, 1906 – April 12, 1975) at the age of 13 went from being a “street child”, living in the slums of St. Louis, sleeping in cardboard shelters, scavenging food from garbage cans while trying to make a living, street-corner dancing with the Jones Family Band, to New York City and the Harlem Renaissance. This “street child” was nothing but ambitious.

Her career would include multiple countries and multiple venues but began with her dancing at Harlem’s Plantation Club, followed, after several auditions, in the chorus line of a touring production of the groundbreaking and hugely successful Broadway revue Shuffle Along (1921) followed by The Chocolate Dandies (1924).

It Happened in Paris

Baker sailed to Paris in 1925, and, at 19, opened on October 2 in La Revue Nègre at Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. Her erotic dancing, appearing practically nude onstage, made her an instant success. After a successful tour of Europe, she broke her contract and returned to France in 1926 to star at the Folies Bergère, setting the standard for her future acts.

Her performance in the revue Un vent de folie in 1927 caused a sensation in the city. Her costume, consisting of only a short skirt of artificial bananas and a beaded necklace, became an iconic image and a symbol both of the Jazz Age and the Roaring Twenties. Her success coincided with the 1925 Exposition des Arts Décoratifs, which renewed an interest in non-Western forms of art, including African, where Baker represented one aspect of that interest.

In later shows in Paris, she was often accompanied on stage by her pet cheetah “Chiquita,” who was adorned with a diamond collar. The cheetah frequently escaped into the orchestra pit, where it terrorized the musicians, adding another element of excitement to the show.

A French African-American Star

Dubbed the “Black Venus”, the “Black Pearl”, the “Bronze Venus”, and the “Creole Goddess”, Baker became the most successful American entertainer working in France. Ernest Hemingway called her “the most sensational woman anyone ever saw” and spent hours talking with her in Paris bars. Picasso painted her alluring beauty. Jean Cocteau became friendly with her and helped vault her to international stardom. That stardom made Baker a marketing sensation, endorsing a host of products including “Bakerfix,” her hair gel, along with bananas, shoes, and cosmetics.

A Yugoslavian Adventure

In 1929, Baker became the first African-American star to visit Yugoslavia, traveling through Central Europe via the Orient Express. During her travels, Baker was accompanied by “Count” Giuseppe Pepito Abatino. Baker had met Abatino, a Sicilian former stonemason who passed himself off as a count, and who persuaded her to let him manage her. In addition to management, he was also her lover; although the two couldn’t marry because Baker was still married to her second husband, Willie Baker – the source of her last name.

Baker’s Assimilation

During this period, she released her most successful song, “J’ai deux amours” (1931). The song expresses the sentiment that “I have two loves, my country and Paris.” It has been noted, “by the 1930’s, Baker’s assimilation into French popular culture was completed by her association with this song,”

JOSEPHINE BAKER PUBLICITY PHOTOGRAPH (1930)

Josephine Baker on Screen

Baker starred in four films that found success only in Europe: the silent films Siren of the Tropics (1927), and Fausse Alerte in 1940 and the sound films Zouzou (1934) and Princesse Tam Tam. Siren of the Tropics features the ‘primitive-to-Parisienne’ narrative that would become the staple of Baker’s cinema career. It also exploited her comic stage persona based on loose-limbed athleticism and artful clumsiness.”

La Creole (1933)

Opera as Well as Bananas

In 1934, she took the lead in a revival of Jacques Offenbach‘s opera La créole, which premiered in December for a six-month run at the Théâtre Marigny on the Champs-Élysées. In preparation for her performances, she went through months of training with a vocal coach. In the words of Shirley Bassey, who has cited Baker as her primary influence, “… she went from a petite danseuse sauvage with a decent voice to la grande diva magnifique … I swear in all my life I have never seen, and probably never shall see again, such a spectacular singer and performer.”

But Not in the USA

Despite her popularity in France, Baker never attained the equivalent reputation in America. Her star turn in a 1936 revival of Broadway’s Ziegfeld Follies was not commercially successful. Time magazine described her as a “Negro wench … whose dancing and singing might be topped anywhere outside of Paris”, while other critics said her voice was “too thin” and “dwarf-like” to fill the Winter Garden Theatre. Baker, heartbroken by the reviews, returned to Paris in 1937, married the French industrialist Jean Lion, and became a French citizen.

World War II In Paris

In September 1939, when France declared war on Germany, Baker was recruited by the Deuxième Bureau, the French military intelligence agency, as an “honorable correspondent”. Baker worked with the head of French counterintelligence . She socialized with the Germans at embassies, ministries, night clubs, charming them while secretly gathering information. Her café-society fame enabled her to rub shoulders with those in the know, from high-ranking Japanese officials to Italian and Vichy bureaucrats.

In the South of France

When the Germans invaded France, Baker left Paris and went to the Château des Milandes, her home in the Dordogne in the south of France. As an entertainer, Baker had continued moving around Europe visiting neutral nations. She collected information regarding airfields, harbors, and German troop concentrations in the West of France, which was then transmitted to England. Her notes were written in invisible ink on Baker’s sheet music.

In North Africa

In 1941, she and her entourage went to the French colonies in North Africa. The stated reason was Baker’s health (since she was recovering from another case of pneumonia) but the real reason was to continue helping the Resistance. From a base in Morocco, she made tours of Spain, pinning notes with the gathered information inside her underwear (counting on her celebrity to avoid a strip search).

After recuperating from a hysterectomy, peritonitis and then sepsis, she started touring North Africa, entertaining British, French, and American soldiers. The Free French had no organized entertainment network for their troops, so Baker and her entourage managed on their own. They allowed no civilians and charged no admission.

After the War

Following Germany’s surrendered, Baker was awarded the Resistance Medal by the French Committee of National Liberation, the Croix de Guerre by the French military, and was named a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur by General Charles de Gaulle.

In 1949, a reinvented Baker returned in triumph to the Folies Bergère. Bolstered by recognition of her wartime heroism, Baker the performer assumed a new gravitas, unafraid to take on serious music or subject matter. The engagement was a rousing success and reestablished Baker as one of Paris’ pre-eminent entertainers.

Back To The US

In 1951 Baker was invited back to the United States for a nightclub engagement in Miami. After winning a public battle over desegregating the club’s audience, Baker followed up her sold-out run at the club with a national tour. Rave reviews and enthusiastic audiences accompanied her everywhere, climaxed by a parade in Harlem in honor of her new title: NAACP‘s “Woman of the Year”.

The Stork Club and Walter Winchell

An incident at New York’s Stork Club in October 1951 interrupted and overturned her plans. Baker criticized the club’s unwritten policy of discouraging Black patrons, then scolded columnist Walter Winchell, an old ally, for not rising to her defense. Winchell responded swiftly a series of harsh public rebukes, including accusations of Communist sympathies (a serious charge at the time). The ensuing publicity resulted in the termination of Baker’s work visa, forcing her to cancel all her engagements and return to France. It was almost a decade before U.S. officials allowed her back into the country.

Nobody Want’s Me!

Baker faced financial troubles in her later year, commenting, “Nobody wants me, they’ve forgotten me”; but family members encouraged her to continue performing. In 1973 she performed at Carnegie Hall to a standing ovation. The following year, she appeared in a Royal Variety Performance at the London Palladium, and then at the Monegasque Red Cross Gala, celebrating her 50 years in French show business.

Advancing years and exhaustion began to take their toll; she sometimes had trouble remembering lyrics, and her speeches between songs tended to ramble. However, Baker was back on stage at the Olympia in Paris in 1968, in Belgrade and at Carnegie Hall in 1973 and at the Royal Variety Performance at the London Palladium and at the Gala du Cirque in Paris in 1974.

The Closing Act

On April 8, 1975, Baker starred in a retrospective revue at the Bobino in Paris, Joséphine à Bobino 1975, celebrating her 50 years in show business. The revue, financed by Prince Rainier, Princess Grace, and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, opened to rave reviews. The opening-night audience included Sophia Loren, Mick Jagger, Shirley Bassey, Diana Ross and Liza Minnelli.

Four days later Baker was found lying peacefully in her bed surrounded by newspapers with glowing reviews of her performance. She was taken to Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, where she died, aged 68, on April 12, 1975.

Baker received a full Catholic funeral at L’Église de la Madeleine, attracting more than 20,000 mourners followed by a huge procession, She was the only American-born woman to receive full French military honors.

Panthéon in Paris

In May 2021 an online petition was set up asking that Joséphine Baker be honored by being reburied at the Panthéon in Paris or being granted Panthéon honours, which would make her only the sixth woman so honored at the mausoleum. In August 2021, French President, Emmanuel Macron, announced that Baker’s remains would be reburied at the Panthéon in November 2021. Her son, Claude Bouillon-Baker, requested that her body remain in Monaco. Respecting the family wishes, a symbolic casket containing soil from various locations where Baker had lived, would be carried by the French Air and Space Force in a parade in Paris before a ceremony at the Panthéon where the casket would be interred. The ceremony took place on Tuesday, November 30, 2021, with Josephine Baker becoming the first black woman to be honored in the secular temple to the “great men” of the French Republic.

So Much More Joséphine Baker

This blog is but an overview of Josephine Baker’s life. To appreciate the full extent of her remarkable life, what she did, what she accomplished and her legacy, please visit the source, Wikipedia’s, Joséphine Baker.

Her Official Website

- African American Movie Memorabilia

- African Americana

- Black History

- Celebrating Women’s HistoryI Film

- Celebrity Photographs

- Current Exhibit

- Famous Female Vocalists

- Famous Hollywood Portrait Photographers

- Featured

- Film & Movie Star Photographs

- Film Noir

- Film Scripts

- Hollywood History

- Jazz Singers & Musicians

- LGBTQ Cultural History

- LGBTQ Theater History

- Lobby Cards

- Movie Memorabilia

- Movie Posters

- New York Book Fair

- Pressbooks

- Scene Stills

- Star Power

- Vintage Original Horror Film Photographs

- Vintage Original Movie Scripts & Books

- Vintage Original Publicity Photographs

- Vintage Original Studio Photographs

- WalterFilm