The Case Of Film Noir

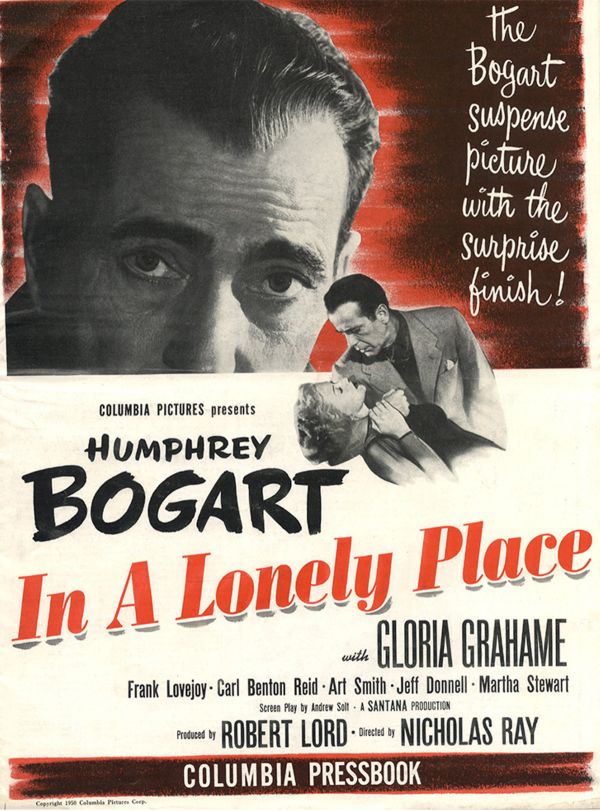

The above image is a 1950 Vintage original 12 x 16” (30 x 40 cm.) Columbia Picture’s Campaign Book, 16 pp.

In A Lonely Place, Is classic film noir, now on the National Film Registry, about a screenwriter asked to adapt a trashy bestseller.

What Is Film Noir?

The term film noir, French for ‘black film’ (literal) or ‘dark film’ (closer meaning), has come to describe stylish Hollywood crime dramas, particularly those that emphasize cynical attitudes and motivations. However, at the time of their release, these films were referred to as “melodramas“. It wasn’t until the 1970s that cinema historians and critics came to define the category retrospectively as Film Noir.

Noir’s Classic Period

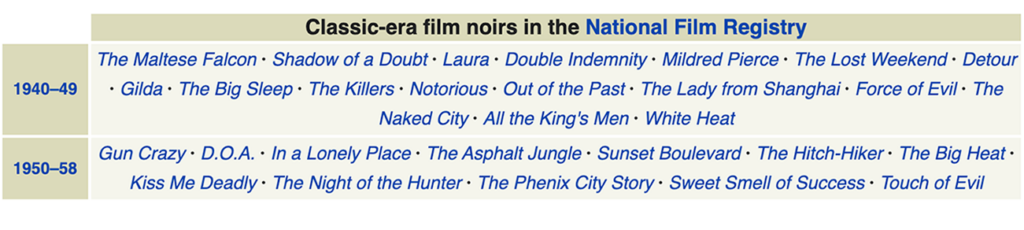

The 1940s and 1950s are generally regarded as the “classic period” of American film noir. Films of this era are associated with a low-key, black-and-white visual style with many of the prototypical stories and much of their attitude derived from the hardboiled school of crime fiction that emerged in the United States during the Great Depression.

DEAD RECKONING (1947) Humphrey Bogart & Lizabeth Scott

Humphrey Bogart and Lizabeth Scott embrace while she holds a gun in her right hand in this film noir.

Hitler’s Noir Contribution

German Expressionism, an artistic movement of the 1910s and 1920s that involved theater, music, photography, painting, sculpture and architecture, as well as cinema, was a major contributing factor to the aesthetics of film noir. Incidentally, Adolf Hitler’s rise to power and the threat of Nazism prompted the emigration of many film artists working in Germany, who had been involved in or studied the Expressionist movement.

Directors such as Fritz Lang, Jacques Tourneur, Robert Siodmak and Michael Curtiz fled Germany, providing Hollywood with a dramatically shadowed lighting style and a psychologically expressive approach to visual composition (mise-en-scène). There, they made some of the most famous classic noirs.

Repertory Of Plots

Film noir encompasses a repertory of plots, which include the following, where the central figure may be a private investigator: (The Big Sleep), a plainclothes police officer (The Big Heat), an aging boxer (The Set-Up), a hapless grifter (Night and the City), a law-abiding citizen lured into a life of crime (Gun Crazy), or simply a victim of circumstance (D.O.A.).

THE BIG SLEEP (1946) Humphrey Bogart & Lauren Bacall

Lauren Bacall removes the bandages to reveal Humphrey Bogart’s face.

1930 Hollywood

There were many films and directors that produced films that forecast the coming of film noir. Josef von Sternberg films such as Shanghai Express (1932) and The Devil Is a Woman (1935), with their hothouse eroticism and baroque visual style anticipated central elements of classic noir. The commercial and critical success of Sternberg’s silent Underworld (1927) was largely responsible for spurring a trend of Hollywood gangster films. Successful films in that genre such as Little Caesar (1931), The Public Enemy (1931) and Scarface (1932) demonstrated that there was an audience for crime dramas with morally reprehensible protagonists.

DEAD END (1937) Humphrey Bogart & Joel McCrea

“Gangster Baby Face Martin (Bogart) makes a nostalgic visit to the slums of NYC’s East Side where he grew up, but his mother (Main) rejects him, and his old girlfriend (Trevor) is now a whore. He and sidekick Hunk (Jenkins) have a contretemps with Baby Face’s childhood rival Dave Connell (McCrea) which escalates until Dave kills the gangster.”

Among films not considered noir, perhaps none had a greater effect on the development of the genre than Citizen Kane (1941), directed by Orson Welles. Its visual intricacy and complex, voiceover narrative structure is echoed in dozens of classic films noir.

Noir Literary Sources

Dashiell Hammett & James M. Cain

The primary literary influence on film noir was the hardboiled school of American detective and crime fiction. It was led in its early years by such writers as Dashiell Hammett (whose first novel, Red Harvest, was published in 1929) and James M. Cain (whose The Postman Always Rings Twice appeared five years later). The classic film noirs The Maltese Falcon (1941) and The Glass Key (1942) were based on novels by Hammett; Cain’s novels provided the basis for Double Indemnity (1944), Mildred Pierce (1945), The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), and Slightly Scarlet (1956; adapted from Love’s Lovely Counterfeit).

THE POSTMAN ALWAYS RINGS TWICE (1946) Lana Turner & John Garfield

Scene still from the noir drama based on the James M. Cain novel. The story of an unhappily married woman, who, with a drifter, plans and carries out the murder of her husband, is one of the best remembered, most atmospheric and sexually tense films.

Raymond Chandler

Raymond Chandler, who debuted as a novelist with The Big Sleep in 1939, soon became the most famous author of the hardboiled school. Not only were Chandler’s novels turned into major noirs—Murder, My Sweet (1944; adapted from Farewell, My Lovely), The Big Sleep (1946), and Lady in the Lake (1947)—he was an important screenwriter in the genre as well, producing the scripts for Double Indemnity, The Blue Dahlia (1946), and Strangers on a Train (1951).

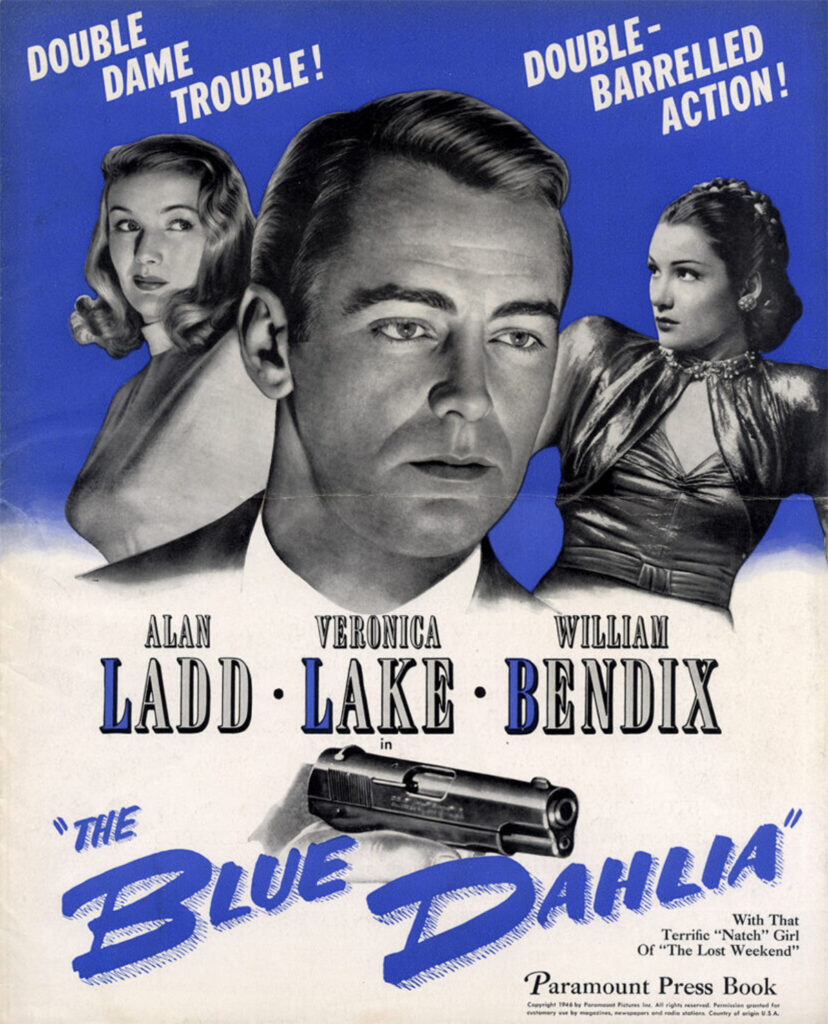

THE BLUE DALHIA (1946) Pressbook

Raymon Chandler’s only solo screenwriting effort, for this now classic film noir which starred Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake.It is a story of a returning war veteran who discovers his wife is having an affair, and then finds her murdered, with him as the lead suspect.

Cornell Woolrich

For much of the 1940s, one of the most prolific and successful authors of this often downbeat brand of suspense tale was Cornell Woolrich (sometimes under the pseudonym George Hopley or William Irish). No writer’s published work provided the basis for more films noir of the classic period than Woolrich’s: thirteen in all, including Black Angel (1946), Deadline at Dawn (1946), and Fear in the Night (1947).

W. R. Burnett

Another crucial literary source for film noir was W. R. Burnett, whose first novel to be published was Little Caesar, in 1929. It was turned into a hit for Warner Bros. in 1931; the following year, Burnett was hired to write dialogue for Scarface, while The Beast of the City (1932) was adapted from one of his stories. Burnett’s characteristic narrative approach fell somewhere between that of the quintessential hardboiled writers and their noir fiction compatriots—his protagonists were often heroic in their own way, which happened to be that of the gangster. During the classic era, his work, either as author or screenwriter, was the basis for seven films, including three of the most famous: High Sierra (1941), This Gun for Hire (1942), and The Asphalt Jungle (1950).

Noir’s Ladies and Private Eyes

Thematically, films noir were most exceptional for the relative frequency with which they centered on portrayals of women of questionable virtue—a focus that had become rare in Hollywood films after the mid-1930s and the end of the pre-Code era. The signal film in this vein was Double Indemnity, directed by Billy Wilder; setting the mold was Barbara Stanwyck‘s unforgettable femme fatale, Phyllis Dietrichson—an apparent nod to Marlene Dietrich, who had built her extraordinary career playing such characters for Sternberg.

An A-level feature, Double Indemnity‘s commercial success and seven Oscar nominations made it probably the most influential of the early noirs. A slew of now-renowned noir “bad girls” followed, such as those played by Rita Hayworth in Gilda (1946), Lana Turner in The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), Ava Gardner in The Killers (1946), and Jane Greer in Out of the Past (1947).

Lana Turner (1945) MGM Portrait

Stunning classic and sexy portrait image of a platinum blonde Lana Turner to publicize her now iconic role in THE POSTMAN ALWAYS RINGS TWICE (1946). Perhaps her finest work from the 1940s, writer James M. Cain told Lana that she was perfect in the role of Cora in this noir-influenced adaptation of his crime novel.

Lauren Bacall (1946) The Big Sleep

Absolutely stunning portrait of a sultry Lauren Bacall, utilized to promote this classic noir.

Rita Hayworth (1946) Gilda

One of the quintessential film noir titles, with star Rita Hayworth becoming film history’s iconic femme fatale. This image is from a sitting which is amongst the most famous publicity photo shoots of all time.

The iconic noir counterpart to the femme fatale, the private eye, came to the fore in films such as The Maltese Falcon (1941), with Humphrey Bogart as Sam Spade, and Murder, My Sweet (1944), with Dick Powell as Philip Marlowe.

Noir Directors

Many of the films noir still remembered were A-list productions by well-known film makers. Debuting as a director with The Maltese Falcon (1941), John Huston followed with Key Largo (1948) and The Asphalt Jungle (1950). Opinion is divided on the noir status of several Alfred Hitchcock thrillers from the era; at least four qualify by consensus: Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Notorious (1946), Strangers on a Train (1951) and The Wrong Man (1956). Otto Preminger‘s success with Laura (1944) made his name and helped demonstrate noir’s adaptability to a high-gloss 20th Century-Fox presentation.

LAURA (1944) Gene Tierney & Vincent Price

Portrait of Gene Tierney and Vincent Price for Otto Preminger film noir masterpiece.

Among Hollywood’s most celebrated directors of the era, arguably none worked more often in a noir mode than Preminger; his other noirs include Fallen Angel (1945), Whirlpool (1949), Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950) and Angel Face (1952). A half-decade after Double Indemnity and The Lost Weekend, Billy Wilder made Sunset Boulevard (1950) and Ace in the Hole (1951), noirs that were not so much crime dramas as satires on Hollywood and the news media respectively.

SUNSET BOULEVARD (1950) William Holden, Gloria Swanson & Ercih von Stroheim

This classic image depicts Erich von Stroheim as Max driving Joe Gillis (William Holden) and Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) through the streets of Hollywood on their way to Paramount Studios.

In a Lonely Place (1950) (see cover image) was Nicholas Ray‘s breakthrough; his other noirs include his debut, They Live by Night (1948) and On Dangerous Ground (1952), noted for their unusually sympathetic treatment of characters alienated from the social mainstream.

Orson Welles had notorious problems with financing but his three film noirs were well-budgeted: The Lady from Shanghai (1947) received top-level, “prestige” backing, while The Stranger (1946), his most conventional film, and Touch of Evil (1958), an unmistakably personal work, were funded at levels lower but still commensurate with headlining releases.

THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI (1947) Rita Hayworth

Rita Hayworth and African American actress Evelyn Ellis in a scene from Orson Welles’ film noir.

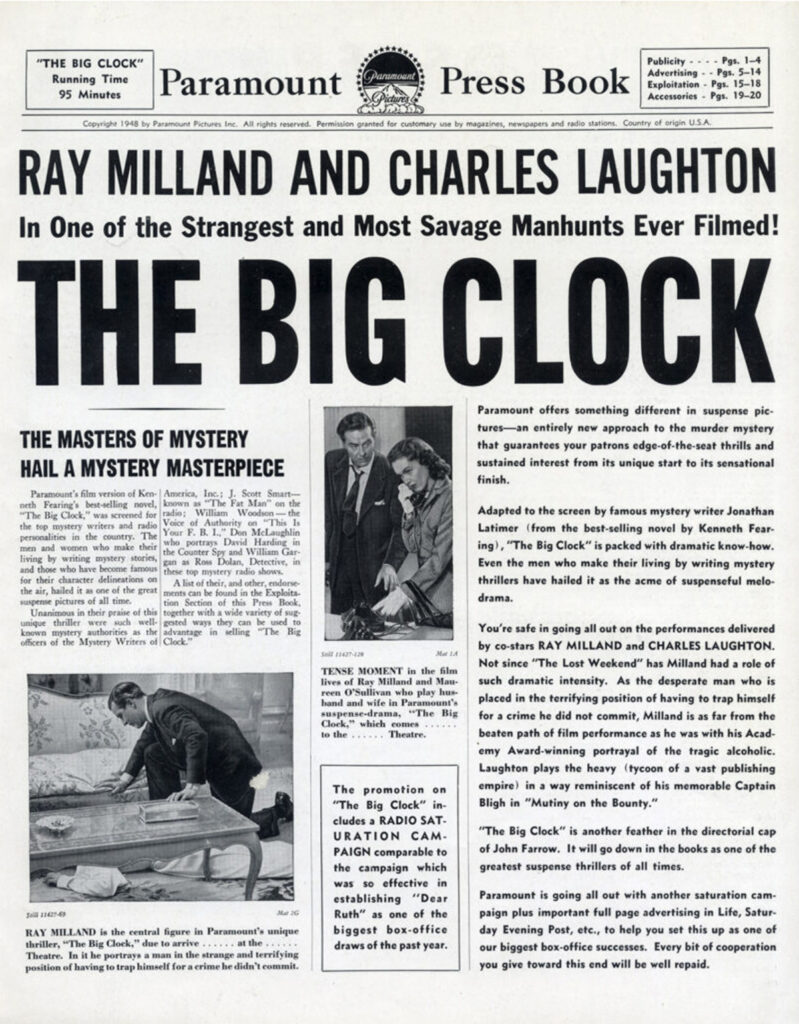

THE BIG CLOCK (1948) Pressbook

This film noir thriller directed by John Farrow and starring Ray Milland, Maureen O’Sullivan, and Charles Laughton is a story of a ruthless magazine publisher who commits murder and then frames his lead editor for it.

Film Noir Goes On

Film Noir continued through the 1950’s evolving into the Neo-Noir in the 1960s and 1970s. It also made its mark outside the United States in England and Europe. For more information on Noir and its evolution, please visit our Wikipedia Reference that provides the content for this blog.

- African American Movie Memorabilia

- African Americana

- Black History

- Celebrating Women’s HistoryI Film

- Celebrity Photographs

- Current Exhibit

- Famous Female Vocalists

- Famous Hollywood Portrait Photographers

- Featured

- Film & Movie Star Photographs

- Film Noir

- Film Scripts

- Hollywood History

- Jazz Singers & Musicians

- LGBTQ Cultural History

- LGBTQ Theater History

- Lobby Cards

- Movie Memorabilia

- Movie Posters

- New York Book Fair

- Pressbooks

- Scene Stills

- Star Power

- Vintage Original Horror Film Photographs

- Vintage Original Movie Scripts & Books

- Vintage Original Publicity Photographs

- Vintage Original Studio Photographs

- WalterFilm